Suzuki - The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk

Here you can read online Suzuki - The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1934, publisher: Tuttle Publishing, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk

- Author:

- Publisher:Tuttle Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:1934

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The

TRAINING

of the ZEN

Buddhist

MONK

First Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc. edition 1994.

Previously published by Globe Press Books.

Cover Design: Julie Metz

Illustration: Monk Starting on a Pilgrimage (detail), Zench Sato

ISBN 978-1-4629-0145-6

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-86012

This is a facsimile edition of the work originally published in Kyoto by The Eastern Buddhist Society in 1934.

CONTENTS

Page ix

Page 3

Page 23

Page 33

Page 47

Page 73

Page 91

Page 145

(Illustrated with Zinc-cuts)

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Monk Starting on Pilgrimage Plate 1

Asking for Admittance Plate 2

Admittance Refused Plate 3

Night in the Lodging Room Plate 4

Initiated to the Zendo Plate 5

Introduced to Rshi Plate 6

Takuhatsu-ing in the Streets Plate 7

Monthly Collection of Rice Plate 8

Takuhatsu-ing for Daikon Plate 9

Wood-gathering Plate 10

Sweeping Plate 11

Gardening Plate 12

Wrestling Plate 13

Cooking Plate 14

Dining Room Plate 15

Nursing the Sick Plate 16

Sewing and Moxa-burning Plate 17

Shaving Plate 18

Washing Plate 19

Bath-room Plate 20

Work of Service Plate 21

The Revolving of the Prajparamita Sutra Plate 22

The Feeding of the Hungry Ghosts Plate 23

The Front Door of the Zendo Plate 24

The Rear Door of the Zendo Plate 25

Kinhin (Walking Exercise) Plate 26

Bedding Put up Plate 27

Good Night to the Holy Monk Plate 28

Morning Wash Plate 29

Monks Filing up Plate 30

Rshi Ready for a kza Plate 31

Meditation Posture Plate 32

Ready for a Zen Interview Plate 33

Interview with Rshi Plate 34

Deeds of the Utmost Kindness Plate 35

The Warning Staff Plate 36

Deeply Absorbed in Meditation Plate 37

Monks Looking for Zen Passages Plate 38

Seeing Off a Senior Monk Plate 39

Zen Monks on Pilgrimage Plate 40

Tea-ceremony with Rshi Plate 41

Term-end Examination Plate 42

Monks Striking the Large Bell Plate 43

PREFACE

For those who have not read my previous works on Zen Buddhism it may be necessary to say a few words about what Zen is.

Zen ( ch'an in Chinese) is the Japanese word for Sanskrit dhyna, which is usually translated in English by such terms as "meditation," "contemplation," "tranquillisation," "concentration of mind," etc. Buddhism offers for its followers a triple form of discipline: la (morality), Dhyna (meditation), and Praj (intuitive knowledge). Of these, the Dhyna achieved a special development in China when Buddhism passed through the crucible of Chinese psychology. As the result, we can say that Zen has become practically the Chinese modus operandi of Buddhism, especially for the intelligentsia. The philosophy of Zen is, of course, that of Buddhism, especially of the Prajparamita As Zen is a discipline and not a philosophy, it directly deals with life; and this is where Zen has developed its most characteristic features. It may be described as a form of mysticism, but the way it handles its experience is altogether unique. Hence the special designation "Zen Buddhism."

The beginning of Zen in China is traditionally ascribed to the coming of Bodhidharma (Bodai Daruma) from Southern India in the year 520. It took, however, about one hundred and fifty years before Zen was acclimatised as the product of the Chinese genius; for it was about the time of Hu-nng(Yen) and his followers that what is now known as Zen took definite shape to be distinguished from the Indian type of Buddhist mysticism. What are then the specific features of Zen, which have gradually emerged in the history of Buddhist thought in China?

Zen means, as I have said, Dhyna, but in the course of its development in China it has come to identify itself more with Praj (hannya) than with Dhyna ( zenj ). Praj is intuitive knowledge as well as intuitive power itself. The power grows out of Dhyna, but Dhyna in itself does not constitute Praj, and what Zen aims to realise is Praj and not Dhyna. Zen tells us to grasp the truth of nyt, Absolute Emptiness, and this without the mediacy of the intellect or logic. It is to be done by intuition or immediate perception. Hui-nng and Shn-hui (Jinne) emphasised this aspect of Zen, calling it the "abrupt teaching" in contrast to the "gradual teaching" which emphasises Dhyna rather than Praj. Zen, therefore, practically means the living of the Prajparamita.

The teaching of the Prajparamita is no other than the doctrine of nyt, and this is to be briefly explained. nyt which is here translated "emptiness" does not mean nothingness or vacuity or contentlessness. It has an absolute sense and refuses to be expressed in terms of relativity and of formal logic. It is expressible only in terms of contradiction. It cannot be grasped by means of concepts. The only way to understand it is to experience it in oneself. In this respect, therefore, the term nyt belongs more to psychology than to anything else, especially as it is treated in Zen Buddhism. When the masters declare: "Turn south and look at the polar star"; "The bridge flows but the water does not"; "The willow-leaves are not green, the flowers are not red"; etc., they are speaking in terms of their inner experience, and by this inner experience is meant the one which comes to us when mind and body dissolve, and by which all our ordinary ways of looking at the so-called world undergo some fundamental transformation. Naturally, statements issuing out of this sort of experience are full of contradictions and even appear altogether nonsensical. This is inevitable, but Zen finds its peculiar mission here.

What Indian Mahayana Stras state in abstract terms Zen does in concrete terms. Therefore, concrete individual images abound in Zen; in other words, Zen makes use, to a great extent, of poetical expressions; Zen is wedded to poetry.

In the beginning of Zen history, there was no specified method of studying Zen. Those who wished to understand it came to the master, but the latter had no stereotyped instruction to give, for this was impossible in the nature of things. He simply expressed in his own way either by gestures or in words his disapproval of whatever view his disciples might present to him, until he was fully satisfied with them. His dealing with his disciples was quite unique in the annals of spiritual exercises. He struck them with a stick, slapped them in the face, kicked them down to the ground; he gave an incoherent ejaculation, he laughed at them, made sometimes scornful, sometimes satirical, sometimes even abusive remarks, which will surely stagger those who are not used to the ways of a Zen master. This was not due to the irascible character of particular masters; it rather came out of the peculiar nature of the Zen experience, which, with all the means verbal and gesticulatory at his command, the master endeavours to communicate to his truth-seeking disciples. It was no easy task for them to understand this sort of communication. The point was, however, not to understand what came to them from the outside, but to awaken what lies within themselves. The master could not do anything further than indicate the way to it. In consequence of all this, there were not many who could readily grasp the teaching of Zen.

This difficulty, though inherent in the nature of Zen, was relieved a great deal by the development of the koan exercise in the eleventh century. This exercise has now become the special feature of Zen in Japan. Koan, iterally meaning "official document," is a kind of problem given to Zen students for solution, which leads to the realisation of the truth of Zen. The koans are principally taken from the old masters' utterances. Now with a koan before the mind, the student knows where to fix his attention and to find the way to a realisation. Before this, he had to grope altogether in the dark, not knowing where to lay his hand in his search of a light.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

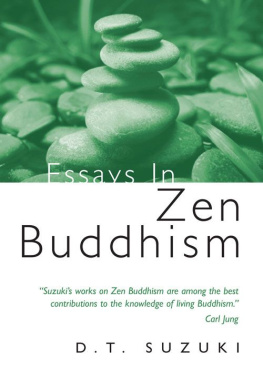

Similar books «The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk»

Look at similar books to The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.