Visit www.davidsuzukibooks.com for exclusive content and information about David Suzukis extensive list of books, including new and upcoming titles.

Vancouver/Berkeley

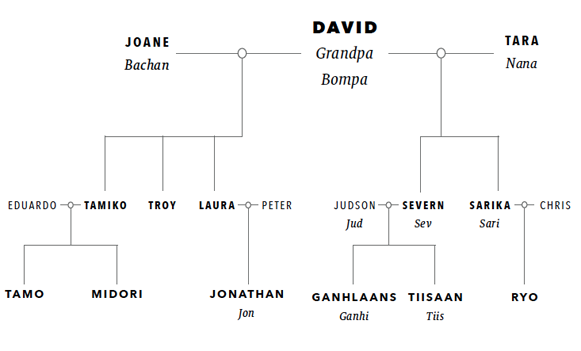

Thank you, Joane and Tara. I could not have done what I did without you, and our children have been my greatest joy.

Copyright 2015 by David Suzuki

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Greystone Books Ltd.

www.greystonebooks.com

David Suzuki Foundation

219-2211 West 4th Avenue

Vancouver BC Canada V6K 4S2

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-77164-088-6 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-77164-089-3 (epub)

Editing by Nancy Flight

Copy editing by Stephanie Fysh

Cover design by Jessica Sullivan and Nayeli Jimenez

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

Note to the Reader

WHEN TAMIKO, MY eldest child, was born, I was overwhelmed with joy at the arrival of another person whom I loved more than my own life. Each of my children has been a wonderful gift who has enriched my life and helped create the person I am today.

I thought fatherhood was the greatest experience of my lifeuntil grandchildren arrived. You see, even in the most wonderful parentchild relationship, there are times when one of us is so pissed off at the other that we scream, fight, pout, or walk off in a huff. Not so with grandchildren. They dont usually live with us, so we dont see each others faults or have strong disagreements. Grandchildren are pure love; they think we are flawless, and they see us as a constant source of encouragement and support. And when they are young, we feel no guilt about spoiling them (isnt that our job?) and then returning them to Mom and Dad to handle the repercussions.

It took me a while to embrace the notion, but over the past several years I have been introducing myself as an elder. In First Nations societies, elders fill a critical role as the keepers of history, tradition, practical knowledge, and wisdom, and so they are treated with great respect and love. Until recently, under the delusion that Im still young, I tried to deny that I am an elder. But now I realize that this is the most important period in my life, and in accepting that Im an elder, I am overwhelmed by the responsibility that this brings. I am obligated to speak the truth now that I am no longer beholden to employers or others who hold some kind of power over me. I have to think about the world that my generation and the boomers who followed are bequeathing to our grandchildren. I am so grateful for the opportunities Ive had in my life and Ive learned a lot from my mistakes and a few successes, and those lessons should be passed on.

Now that I have entered the last part of my lifewhat I call the death zoneI know that death is inevitable and that I could die at any moment. There is nothing morbid in my thoughts; any elder who doesnt think about death is avoiding some serious issues. And those who think that science is somehow going to solve the problem of death or at least stave it off by many more decades are living under a terrible illusion. As a scientist, I know how easy it is to get caught up in the excitement of new discoveries and speculate about all kinds of wonderful possibilities. Remember Richard Nixons war on cancer or George H.W. Bushs war on drugs? Immense amounts of money and effort have been expended to solve these problems, but they are still with us. And I am a biologist, so I understand that aging and death are essential for life and for evolution to occur, especially as conditions are changing so rapidly and require resilience and adaptation. The challenge is not to extend our species lifespan or to conquer death but to ensure that everyone has opportunities to live full and meaningful lives.

Since my grandparents spoke only Japanese and I spoke only English, when I was growing up I was never able to communicate with them beyond superficial greetings and simple exchanges. My mothers parents were so disillusioned with Canada after we lost our rights and were incarcerated during the war that they chose to return to Japan after the war ended. They were on one of the first boats to leave Vancouver and were deposited in the devastation of Hiroshima. Both of my grandparents were dead within a year, so even if I had been able to talk to them as a boy, I wouldnt have had a chance when I was older.

My fathers parents chose to stay in Canada after the war and ended up in London, Ontario. The growing extended Suzuki family would gather for dinner at our grandparents farm on weekends, but, like me, my sisters and cousins couldnt speak Japanese, so we ate at a separate table, where we could chatter away in English. When I had my own family after my grandparents had died, I regretted that I never got to ask them what had motivated them to leave Japan, what it was like when they arrived in Canada, and why they never returned to Japan.

I believe that we learn best by doing, and it has been wonderful to be able to spend time hanging out with my grandchildren. But as I get older, a lot of what I could do in the pastbackpacking, skiing, kayaking, even fishinghas become more difficult, and over the years I have reluctantly done these things less often or given them up. More and more, time with my grandchildren has been spent watching, listening, and talking but not doing.

Remembering my unanswered questions for my grandparents, I have often wondered what I would want to say to my grandchildren before I die. I dont want them to have unanswered questions that they wish they had asked. And so the idea of this book was born. I had hoped that writing it would be like talking to themnot a lecture or a straightforward talk, but a kind of loose stream of ideas where one thought might trigger another on a completely different topic and then loop back again. So I began to write as if I was having a conversationalbeit a one-way conversationwith my grandchildren. But their ages extend from twenty-four years to less than a year old, one of the consequences of having two sets of children who range in age from fifty-five to thirty-two.