By the same author:

I Used to Know That: History

Bad History: How We Got the Past Wrong

The History of the World in Bite-Sized Chunks

I Should Know That: Great Britain

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Michael OMara Books Limited 2014

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78243-217-3 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78243-272-2 in e-book format

Jacket illustration and design by Patrick Knowles

www.mombooks.com

To those who have lived and died before us approximately 107.6 billion people

C ONTENTS

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks go to Louise Dixon, Gabriella Nemeth, Steve Cox and Rod Green for their invaluable help and hard work. I would also like to thank my husband Robin for his sterling support on the home front.

Numbers can reveal much about the history of the world. Their scale or precision can illuminate the sometimes murky and complex history of man, and encapsulate in an instant the enormity or inconsequentiality of an event in the past.

There is also something solid and indisputable about numbers, making them a useful tool for anyone hoping to convey the history of the world in one short book. Thats not to say that numbers cant be exaggerated, massaged, or even blatantly wrong as so often they are and just like words, they too can distort our view of history.

With this in mind, however, numbers do help to provide a sort of filing system for the past. We love to compartmentalize history, reordering it into tidy folders, labelling them with numbers of note. By this means numbers seem to leap out of the annals of history right into our collective consciousness, to remain lodged in our minds long after other facts have fallen away. The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, Martin Luthers ninety-five theses, Henry VIIIs six wives, Marxs six stages of history, all provide testament to the staying power of numbers.

Different types of numbers can alter our perspective on history. Vast numbers inform us how many people are living on the planet or how many millions are massacred in war. (Too often numbers convey the grim realities of life in the past how millions have perished from disease, on the battlefield, or merely through the whims of a single deluded monarch or leader.) Large numbers can illustrate the broad sweep of history, from mass movements of populations to the expansion of empires (and often their sudden demise), the profound effects of industrialization and the growth of a global economy.

Smaller numbers, however, are no less significant: they measure the living details of history, the tiny shifts that may have vast consequences. The perfect proportions of Leonardo da Vincis Vitruvian Man, the components of a piece of eight silver coin, the US constitutions thirteenth amendment, all were to have a lasting impact on the history of the world.

The nature of our past peculiar, extraordinary, often fortuitous can also be wonderfully illustrated by numbers, from the 12,000 molluscs that it took the Phoenicians to make just 1.5 grams of Tyrian purple, to the $15 million paid by the US government for a vast tract of land known as Louisiana. Mythical (or at least partly mythical) stories of the past, such as the Twelve Knights of the Round Table or the Seven Hills of Rome, can also be given validity or symbolic importance by their association with a number (the numbers seven and twelve are recurring favourites).

Armed with numbers, we can also zoom back and forth through time to compare events and achievements, taking in along the way the massive fifteenth-century fleets of the Chinese Admiral Zheng He (whose size wasnt rivalled in the West until the First World War) to statistics showing that by the 1930s one in five Americans owned a car (a number that the UK didnt reach until the 1960s). We can focus for an instant upon those who actually dealt with numbers the astronomers, philosophers, engineers, physicists, many of whom exerted and still exert a far-reaching influence on our history, from the Indian scholar Aryabhata, who came up with the invaluable concept of zero, to the British mathematicians of the Second World War who cracked the Enigma system, thereby changing the outcome of a global war.

The History of the World in Numbers acts as a kind of compendium to some of the most fascinating figures in our history, from the beginnings of early civilization to the upheavals of the Second World War. The books short entries are meant to be succinct and accessible, to provide a wide-ranging view of our past across the globe. They also represent just a toes dip into the huge pool of numbers and history, a subject immeasurably vast and chasm-like. Our hope, nonetheless, is to package the past slightly differently, to provide a book that bears witness to mans many achievements and misdemeanours, all told through the powerful medium of numbers.

Emma Marriott

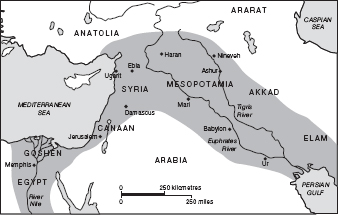

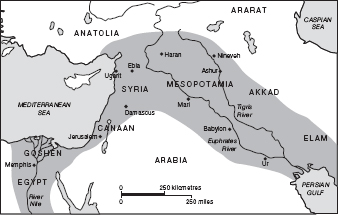

Some 10,000 years ago, most of the worlds edible grasses (32 out of 56) cereals like rice, wheat, barley and corn grew wild in an area known as the Fertile Crescent. In the Americas and Africa, only four varieties grew, and in Western Europe just one (oats). Small wonder, then, that the worlds first farming communities began to develop in this great arc of territory, located in and around the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, running through present-day western Syria, southern Turkey, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon and the western fringes of Iran.

The Fertile Crescent, 10,0004,500 BCE

The regions rich resources of edible plants, which included the wild strains of barley, wheat, lentils, onions and peas, were planted and cultivated by hunter-gatherers living on the plains and hills of the Fertile Crescent. Also plentiful were wild animals suited for domestication goats, sheep, pigs and cattle (four of the five most important domesticated species; the fifth is the horse). This, combined with a climate that initially had sufficient rainfall to support farming without artificial irrigation, provided the vital prerequisites for crop cultivation, the surplus of which eventually enabled people to settle in one place, develop technical skills, and evolve into the worlds earliest civilizations.

The first known system of writing was developed in Sumer, the worlds earliest civilization of southern Mesopotamia, situated in the Fertile Crescent. Early forms of farming had led to permanent settlement in Sumer somewhere between 5500 and 4000 BCE . These farming settlements had grown into small towns, and by 3000 BCE a number of city-states had developed, the largest Uruk, with a population of 40,000.

Each Sumerian city had its own temple precinct that was a place of worship as well as an administrative and governmental centre. These temples stored and distributed community food rations, organized labour for public works, and controlled the trade in raw materials like tin from Afghanistan and copper from Cyprus.

Next page