CHAOS IMAGINED

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2016 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54046-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Meisel, Martin.

Chaos imagined : literature, art, science / Martin Meisel.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16632-4 (cloth : acid-free paper) ISBN 978-0-231-54046-9 (e-book)

1. Literature and society. 2. Chaotic behavior in systemsSocial aspects. 3. Arts and society. 4. Social change. 5. Chaotic behavior in systems in literature. 6. Literature and science. 7. Entropy in literature. I. Title.

PN45.M433 2015

801dc23

2015010548

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

Cover image: plainpicture / Hanka Steidle

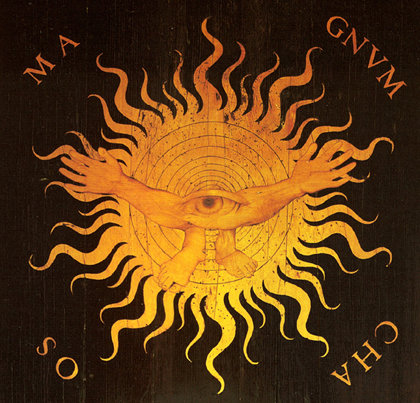

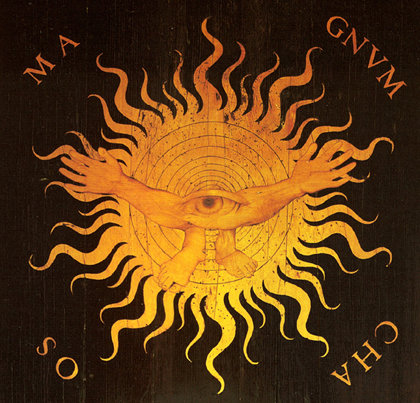

. From an intarsia designed by Lorenzo Lotto and executed by Giovanni Francesco Capoferri, ca. 1527, Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, Bergamo, Italy. See my exegesis in the notes section.

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

To Frederick Laurence Meisel, il miglior fratello,

and Lili Ann Meisel,

with love

CONTENTS

C haos Imagined has been on the stocks for more than a quarter of a century. I once told my wife, Martha, somewhat ruefully, It will last my time; alas, it outlasted hers. She, with patience, humor, and a taste for the unorthodox, helped it on its way, along with many others. How could it be otherwise, with so vast and unconfined a subject? One that trespasses on so many posted territories where I have no license to hunt? In the long list of those to whom I am indebted are a number of institutions and organizations, notably the National Humanities Center in North Carolina, where the work began; the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, where it continued; the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation; and Columbia University, with its rich mix of disciplines and forums and its tolerant encouragement of teaching and thinking outside and across the established lines. One such forum was Columbias University Seminars, and I may now happily express my appreciation to the Seminars Schoff Fund for its help in publication. Material in this book was first presented in the Frank Tannenbaum Lecture to the Fifty-Fourth Annual Meeting of the University Seminars and benefited from discussion there and in the seminar Drama: Text and Performance.

As a work in progress, the manuscript was read in whole or part by a number of friendly critics, and others provided expert advice on particular matters. I am especially grateful for the generous efforts and commentary of Christine Gledhill, David J. Helfand, Jean Howard, Robert G. Hunter, the late Karl Kroeber, Marjorie Perloff, James Shapiro, and Alex Zwerdling, all of whom took time from their own fruitful labors to scrutinize mine, and to others who provided free consultation or much needed reassurance, such as Helene Foley, Jan-Piet Knijff, the late David Rosand, Barrymore Laurence Scherer. I am grateful to Nimet Habachy for insights into the social and performative aspects of musical culture and for her sustaining warmth and enthusiasm. Several anonymous readers for the press helped shape the final form of this book in qualifying their otherwise encouraging readings. Through much of its prolonged gestation, I have taken advantage of the acumen and expertise of my three children: Maude Frances Meisel, especially for matters Russian, literary, and stylistic; Andrew A. W. Meisel, for matters scientific, philosophic, and linguistic; and Joseph Stoddard Meisel, with his informed and rigorous eye in matters historical. Naturally, none felt obliged to stay within those confines.

At the Columbia University Press, Jennifer Crewe has my particular gratitude for wanting to take on such a book in the first place. Among those who have helped navigate the process and make it enjoyable are Michael Haskell, Marisa Pagano, Kathryn Schell, Lisa Hamm as designer, and Rob Fellman as copyeditor. Several generations of remarkable students, in class and out, have also left their traces in the book, as in my thinking. Among those who made a direct contribution, in pursuing a topic or a body of material, are John Bell, Bianca Calabresi, Tamsen Wolff, Alexis Soloski.

A version of part of . Lines from the poem by Wallace Stevens, Connoisseur of Chaos, from The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens, copyright 1954 by Wallace Stevens and copyright renewed 1982 by Holly Stevens, are used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, all rights reserved. Lines from the poem by Howard Nemerov, Angel and Stone, appear courtesy of the Estate of Howard Nemerov. This book is dedicated to my brother, Frederik Meisel, a gifted psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, and his wife Lili, costume designer and fabricator among other things, in gratitude for our lifelong friendship.

The curtain rises. The theater represents a theater.

THE EPILOGUE comes forward.

EPILOGUE: Now, [ladies and] gentlemen, how did you like our play?

Ludwig Tieck, The Topsy-Turvey World (1798)

W hen he began his wildly satirical metaplay of nested theaters-in-the-theater with an epilogue, dismissing the play that follows as a mere formality, Ludwig Tieck was after a provocative bit of estrangement. Inevitably, he ends the performance with a prologue, alerting the audience to what it is supposedly about to see and incidentally completing the well-worn carnival strategy of inversion for enacting the temporary reign of chaos. I too begin with an epilogue, properly capping a historical and thematic exploration of how artists, poets, philosophers, and scientists have attempted to give shape to the imagination of chaos, in the hope that in bringing it forward, I will in effect be bringing it home.

At the very time Tieck was perpetrating his pastiche of burlesque and philosophya time of great social and political turmoila revolution was also brewing in science that would profoundly transform the imagination of chaos. For with the generalization of energy and later of entropy, the twin pillars of the new science of heat, new channels of thought and feeling came into force, changing the face of order and disorder, cosmos and chaos, in human perception and understanding. The revolution wrought by energy took place as well in the realm of values, notably in attitudes toward disruptive change. That wrought by entropy was, conceptually at least, even more disconcerting for traditional thinkers, in its radical contrast with the enduring notion of chaos as energetic turmoil. The alternative, by way of what came to be called the second law of thermodynamics, pointed to a wholly other kind of chaos as a final condition: a depleted, undifferentiated, exhausted sameness, a universal undoing, the heat death of everything, where everythingas Clov puts it in Becketts