Copyright 1999, 2009, 2013 by Benjamin Watson

The Library of Congress has cataloged the previous edition as follows:

Watson, Ben, 1961

Cider, hard and sweet : history, traditions, and making your own / Ben Watson.

2nd ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-881-50819-2 (alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-581-57689-4 (e-book)

1. Cider. I. Title.

TP563.W38 2008

641.3411dc22

2008028918

Third edition ISBN: 978-1-58157-207-0

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages.

Title page: Cidermaking at Log Cabin Farm in Dummerston,

Vermont, in the early 1900s, courtesy of Frances Manix

Illustrations on pages 64 and 77 by Jill Shaffer Hammond

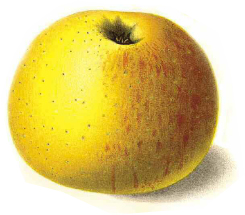

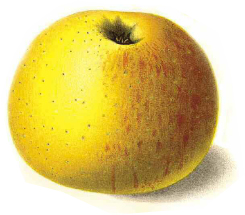

Illustration of American Beauty apple on page 107 by Amanda A. Newton (1912). U.S. Department of Agriculture Pomological Watercolor Collection. Rare and Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, Beltsville, MD 20705

Interior photographs by the author unless otherwise specified

PHOTO CREDITS

Brenda Bailey Collins: pages .

Book design and composition by Eugenie S. Delaney

Published by The Countryman Press, P.O. Box 748, Woodstock, VT 05091

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue,

New York, NY 10110

Printed in the United States of America

In memory of Dan Chaffee (19462007),

Elisabeth Swain (19412008),

and Terry Maloney (19392010)

Acknowledgments

M any cidermakers and apple growers provided either material or moral support during the course of this project. Special thanks go to Judith and Terry Maloney of West County Winery in Colrain, Massachusetts, and Stephen Wood and Louisa Spencer of Farnum Hill Ciders in Lebanon, New Hampshire, for being so generous over the years with both their time and their excellent ciders. Also to Rich Stadnik, my friend, grafting partner, and sounding board at Pups Cider, Greenfield, New Hampshire.

I am deeply indebted to two gentlemen in particular for sharing with me their years of wisdom and experience. Dr. Andrew Lea of Oxfordshire, England, is a food scientist who formerly worked at the Long Ashton Research Station in Bristol. On matters biological, chemical, and historical, his advice and insights have proved invaluable to myself and many other cidermakers, both amateur and professional. Likewise, my friend Tom Burford, a seventh-generation Virginia orchardist, has been my trusted guide to the history and practice of fruit growing.

In the years since this book first appeared, I have been grateful for the friendship and continuing support of Mike Beck, cidermaker and distiller at Uncle Johns Cider Mill in St. Johns, Michigan, and the Shelton family of Vintage Virginia Apples and Albemarle CiderWorks in North Garden, Virginia.

Additional thanks go to Ouida Young, Trish Wesley-Umbrell, Hannah Proctor, Roger Swain, Brenda Bailey Collins, Nicole Leibon, Michael Phillips, David Buchanan, Eduardo Vasquez Coto, and Jason Martel; Homer Dunn, Alysons Orchard, Walpole, New Hampshire; Diane Flynt, Foggy Ridge Cider, Dugspur, Virginia; John Bunker, Fedco Trees, Waterville, Maine; Dick Dunn and the many generous and knowledgeable contributors to The Cider Digest e-group, especially Gary Awdey, Terry Bradshaw, John Howard, Claude Jolicoeur, and Bill Rhyne; Charles McGonegal, AEppelTreow Winery, Burlington, Wisconsin; Dan Young and Nikki Rothwell, Tandem Cider, Suttons Bay, Michigan; John Brett, Tideview Cider, Halifax, Nova Scotia; Grant Howes and Jenifer Dean, County Cider, Picton, Ontario; Christie Higginbottom, Old Sturbridge Village, Sturbridge, Massachusetts; James Asbel, Ciders of Spain, Newport, Rhode Island; Christian Drouin, Domaine Coeur de Lion, Choudray Rabut, Normandy, and all my fellow volunteer organizers at CiderDays in Franklin County, Massachusetts. To the extent that this book succeeds, it truly stands on the shoulders of these and many other experts and enthusiasts.

Preface to the Third Edition

Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richards Almanack

W hen the first edition of this book appeared way back in 1999, it contained some rather audacious claims concerning a cider renaissance that I felt was building throughout North America. Readers at the time could be excused for not believing me. After all, the growth in public awareness and consumption of alcoholic (hard) cider was still glacially slow, and marketing the unfamiliar beverage to consumers remained an uphill battle.

Fast-forward, then, to 2013, as I prepare this updated and revised edition. Sales of hard cider have skyrocketed in the past few years, increasing 65 percent between 2011 and 2012 in supermarket sales alone, and far outpacing the growth of wine (5.6 percent) and craft beer (13 percent). As a category, hard cider still represents only around 0.3 percent of the overall beer and alcoholic beverage market, but this is triple the sales of only a few years ago. Cider, suddenly, is almost everywhere. Many of the new cider drinkers are young, and about half of them are women. The future looks bright.

Granted, much of this growth has been driven by the large national or multinational brands, whose owners have the capital and the distribution channels to get bottles (and now cans) of their product onto store shelves. But at the same time, the number of small, regionally focused craft cideries has continued to increase: there are now around 150 producers in the United States alone, compared to maybe a couple dozen when I first started writing about cider in the late 1990s. And their geographic range continues to spread outside the traditional cider incubators of the Northeast and Northwest. From the Great Lakes region to the South and Southwestit takes real dedication to keep track of all the enthusiasts who are now going commercial, many producing good cider from the get-go. The growth and innovation in the cider world has been compared to the craft beer explosion of the 1980s, which continues to this day.

Whats more, the recent focus on cider has spurred interest around the globe. From ciders traditional hot spots like southwest England, northwest France, and northern Spain, to less well known producing areas like Poland, Mexico, and New Zealand, there is a growing appreciation for the fermented essence of the apple, and as the craft matures, many producers and consumers are learning more: rediscovering and replanting classic old apples that make good cider; appreciating and redefining regional and national styles; and demanding (or making) sophisticated products that challenge the stereotype of hard cider as simply a wine-cooler clone.