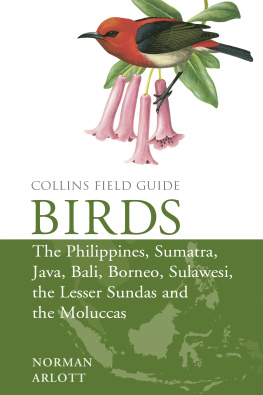

I have been so lucky to work in the Zoology Department of Cambridge University, and to have the privilege of a Fellowship of Pembroke College. I could not imagine a happier or more stimulating environment than these two welcoming homes from home. During the last three decades, I have been fortunate to study cuckoos and their hosts with many wonderful colleagues. The ideas discussed in this book have been developed together with them, and it is a pleasure to acknowledge their inspiration and friendship: Michael Brooke, Terry Burke, Stuart Butchart, William Duckworth, Tibor Fuisz, David Gibbons, Lisle Gibbs, Ian Hartley, Alex Kacelnik, Chris Kelly, Rebecca Kilner, Oliver Krger, Naomi Langmore, Anna Lindholm, Joah Madden, Susan McRae, David Noble, Jarkko Rutila, Michael Sorenson, Claire Spottiswoode, Martin Stevens, Ian Stewart, Cassie Stoddard, Rose Thorogood and Justin Welbergen. I also thank the Natural Environment Research Council and the Royal Society for their generous funding of our studies.

It is a pleasure, too, to thank the National Trust, for giving me the freedom of the nature reserve of Wicken Fen, and the staff there for their encouragement and friendship over many years: Lois Baker, Wilf Barnes, Ian Barton, Tim Bennett, Matthew Chatfield, Joan Childs, Adrian Colston, Howard Cooper, Mark Cornell, Paula Curtis, Anita Escott, John Hughes, Jenny Hupe, Kevin James, Debbie Jones, Jenny Kershaw, Grant Lahore, Carol Laidlaw, Martin Lester, Sandy MacIntosh, Tracey McLean, Ian Reid, Andy Ross, Ralph Sargeant, Isabel Sedgwick, James Selby, Mike Selby, Chris Soans, Karen Staines, Jack Watson, Jake Williams and Ruby Wood.

The bird ringers of the Wicken Fen Group have generously shared their data on bird populations on the fen. I particularly thank Chris Thorne, who has led this group since 1971 , together with Peter Bircham, Phil Harris, Michael Holdsworth, Jo Jones, Neil Larner and Alan Wadsworth.

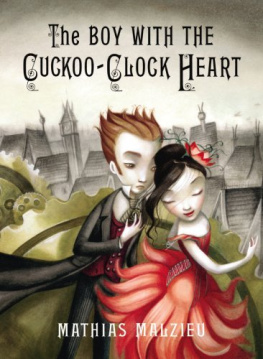

Im honoured that James McCallums drawings grace this book. He is not only a brilliant artist but also an original observer of wildlife, always drawing in the field and spending long hours getting to know the behaviour of his subjects. His drawings are full of light and movement, bringing the dramas of nature straight to the page. They make me smile and long to go out to the fens again, inspired by his artistic eye to have a fresh look at cuckoos and their hosts.

It is a privilege to illustrate the book with Richard Nicolls award-winning photographs of cuckoos and reed warblers, taken on Wicken Fen. They show that watching these birds is at once both a beautiful and an astonishing experience. I also thank Charles Tyler for his wonderful photographs of cuckoos and meadow pipits, taken on Dartmoor. Claire Spottiswoode has been generous in allowing me to include her photographs, taken in Africa, of egg signatures in hosts and parasites, and of honeyguide chicks with their murderous bill hooks. Others who have generously provided photographs are Bill Carr (courtesy of Alan and Margery Wilkins), Juha Haikola, Dave Leech, Helge Srensen, Artur Stankiewicz, Keita Tanaka and Ian Wyllie.

Tim Birkhead, Jeremy Mynott and my wonderful editor at Bloomsbury, Bill Swainson, read the whole manuscript and gave excellent advice on an early draft. I also thank Becky Alexander, Anna Simpson and Imogen Corke at Bloomsbury for their expert help at guiding the manuscript through to publication, and Hugh Brazier for superb copy-editing. For help with particular chapters, I thank Joanna Bellis (for cuckoos in medieval poetry), Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Tim Dee, Hildegard Diemberger, Chris Hewson, Rebecca Kilner, David Lahti, Naomi Langmore, Audrey Meaney (for translating the cuckoo riddle in The Exeter Book from the Old English), Michael Reeve, Norman Sills, Claire Spottiswoode, Keita Tanaka, Chris Thorne and Rose Thorogood.

My greatest thanks, as always, are to my wife Jan and my daughters Hannah and Alice.

Nick Davies is Professor of Behavioural Ecology at the University of Cambridge, and a Fellow of Pembroke College. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society. His cuckoo research has been presented on BBC4 Radio, and as a BBC film, produced by Mike Birkhead and narrated by David Attenborough. His previous books include Cuckoos, Cowbirds and other Cheats , which won Best Book of the Year from the British Trust for Ornithology and British Birds Magazine .

James McCallum is a graduate of The Royal College of Art, best known for his watercolour paintings of the natural world, particularly birds. James was specially commissioned to create the illustrations for this book, observing the cuckoos in Wicken Fen, Cambridgeshire, over three months. He lives in Norfolk.

Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats

An Introduction to Behavioural Ecology

Dunnock Behaviour and Social Evolution

Reed warbler feeding a cuckoo nestling, days old, with a bill-full of flies.

Reach Lode, May 2014 .

Is there anything more extraordinary in the natural world?

Early morning, a still summers day in mid-July, not a breath of wind; Im searching along the edge of a reed-fringed ditch on Wicken Fen, a patch of ancient fenland just north of Cambridge, and Britains oldest nature reserve. This is a vast, flat landscape; big skies encircle me to the horizon and reflect in the water below, so sometimes I feel I am floating through the sky itself. The white sails of an old wind pump shine brightly in the sunshine. A marsh harrier appears over the reed tops and drifts close by on upswept wings, a young moorhen in its talons. On the path, there are fresh molehills of black peaty soil, the matted remains of old fen vegetation. The peat is resting on a bed of water and, as I walk along, the ground sways gently below my feet.

Just ahead, in the middle of the ditch, a reed twitches. From that exact spot I hear a loud, high-pitched and persistent, quivering call: tsi... tsi... tsi... tsi... I approach slowly and with a long hazel stick, I gently part the reeds. The calling ceases. In the silence, I hear the dew that I have dislodged from the leaves dropping into the water below. Hidden in the darkness, halfway up the reeds, is a reed warblers nest. Its a neat cup, woven from thin strips of old reed and suspended from three vertical stems about a metre above the water surface. Sprawled on top, with its wings draped over the nest rim on either side, is an enormous common cuckoo chick. It is two weeks old, fully feathered, and it sits perfectly still, with its bill shut tight, but it is watching me intently through brown beady eyes.

I lean out from the bank to get a better look; as I do so, the cuckoo suddenly rears up, its head feathers erect, and it opens its beak wide to reveal its gape, a blaze of bright orange. Then it makes a lunge towards me. Instinctively, I withdraw my hand as if expecting an attack. My heart is beating fast, but then I find Im smiling in admiration at the cuckoos show of bravery. We look at each other for a moment; then I withdraw my stick and the reeds spring back, but not completely. Now there is a little gap through which I can watch the cuckoo from the bank just five metres away. I sit quietly and focus on it with my binoculars.

After a few minutes, the reeds twitch once again and a reed warbler emerges from the forest of reed stems, clinging to a reed just above the nest. It has a bright blue damselfly in its bill. The warbler gazes down and appears tiny next to the monstrous cuckoo chick below, some five times the warblers own weight. The cuckoo immediately begins a frenzy of calling, vibrating its open gape. Without a moments hesitation, the warbler bows deep into the enormous mouth to deliver the food. As it does so, the reed warblers head is almost completely engulfed. For a brief moment its small eye lies buried at the base of the gape, right next to the cuckoos large eye, and the warbler seems to risk being devoured itself. But the warbler withdraws just before the large gape clamps shut on the prey, leaving the tip of the damselflys abdomen sticking out. Another twitch of the reeds, and the warbler slips off to search for another meal.

Next page