I have learned to look on nature

Not as in the hour of thoughtless youth,

But hearing oftentimes

The still sad music of humanity

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

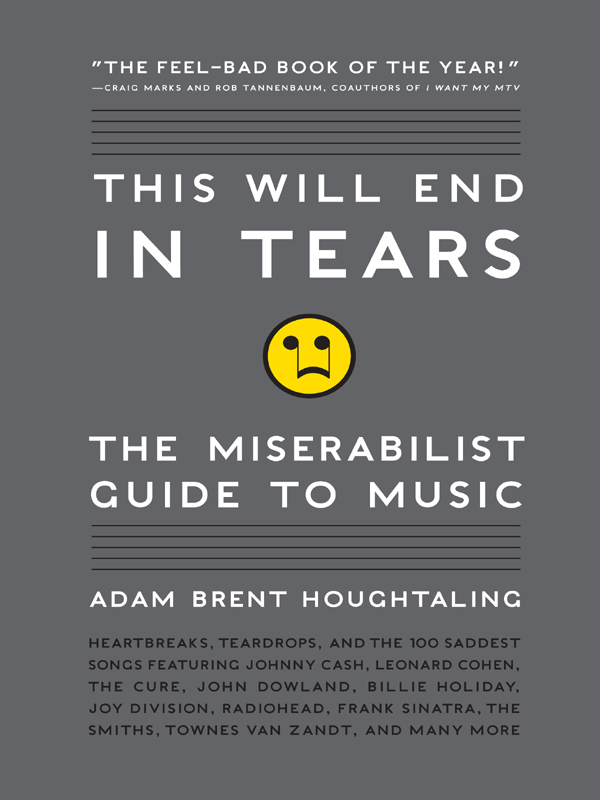

I ts a perfectly gray winter Sunday in Brooklyn. The air is brisk but comfortable, and the streets are just shy of empty. Looking for a suitable soundtrack for my walk to the subway, I pull my phone out of my jacket pocket and scroll through the list of artists I had compiled (randomly, over time, as one does): David Ackles, American Music Club, Patsy Cline, Billie Holiday, Echo and the Bunnymen, Townes Van Zandt, Low, Joy Division, Johnny Cash, Portishead, Radiohead, Gyrgi Ligeti, James Carr, Tindersticks, David Sylvian, Robert Wyatt

Looking over the list, I notice that almost every artist, regardless of genre or the decade in which they were active, has a natural affinity for melancholy, the dark stuff, an elemental leaning toward the shadowy side. Throughout my life, much of the music that has most affected mecertainly from my late teen years onhas come from artists with this defining attribute, this uncommon understanding of the varying shades of sorrow. They all manage to own misery, and to infuse desperation, loneliness, heartbreak, grief, and ponderous wonder into their work in a manner that sets them apart.

Most of my favorite songs are sad songs, and I know Im not alone. The devotees of Miserabilist music are not confined to any single genre but seek out the downcast heart of song no matter where it may lie. They lower the shades and listen reverentially in the half-light to Skip James, Nick Drake, and Morrissey. They wait anxiously for new albums from the Cure, Leonard Cohen, and the Blue Nile and buy up the deep catalogs of Nina Simone, George Jones, and Scott Walker.

I soon began to wonder, What is it about these artists that makes them more attuned to grief? What makes Billie Holidays voice such a perfect vessel for sadness? How does a piece of music such as Samuel Barbers heartbreaking Adagio for Strings or Radioheads How to Disappear Completely work on our brains to induce feelings of sadness? And how do those same songs somehow also contain the ability to make us happy?

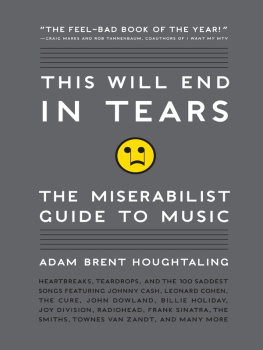

This book was born partly of the struggle to comprehend what Winston Churchill infamously referred to as his Black Dog. Its an attempt to bridge that bitter, unpredictable purgatory of depression with song, an indisputable source of joy, and celebrate the mean between the two: melancholy, in a perhaps bygone sense of the word.

In the liner notes for the ECM recording of modern interpretations of lachrymose sixteenth-century composer John Dowlands songs, In Darkness Let Me Dwell , composer Robert White notes the connection between Dowlands fascination with the lachrimal, accompanied by the larger Elizabethan celebration of melancholy, and our current preoccupation with depression, saying, What his age knew, and we sometimes lose sight of, is that meditating on a beautiful expression of sadness can help to provide a thoroughly uplifting sense of consolation. Sting, who recorded an albums worth of Dowland material on 2006s Songs from the Labyrinth , defined the vital difference between depression and melancholy while discussing Dowlands work, saying, I think depression is different to melancholy. Depression is a clinical condition. Melancholy comes about through self-reflection. And its not necessarily a bad thing to be melancholic.

In William Styrons Darkness Visible , the author suggests that depression lacks the artful command of melancholia. To him, depression is a noun with a bland tonality and a true wimp of a word for such a major illness. (Later in the book he chronicles a number of the artists who have spent their creative spurs giving shape and vocabulary to melancholy, including the suffering that often touches the music of Beethoven, of Schumann, and Mahler, and permeates the darker cantatas of Bach.) But while melancholy can and should be celebrated as a natural part of life that allows our bodies to recover from traumas and disappointments and provides the opportunity to learn and grow, the knotty grip of true depression can be a great ruiner of lives and is to be treated as such. Unfortunately, the two have become entwined by a culture armed with abundant pharmacology and an honest-to-goodness happiness industry.

Consider this book a small stone cast in the war against chasing the healthy aspects of gloom awayto do battle with that is to struggle against what it is to be human, to misunderstand happiness, and to dismiss the possible catharsis afforded by the artists and songs represented in this book.

This is not meant to be a comprehensive exercise in summing up the Western worlds musical malaise, but rather an attempt to coalesce disparate artists separated by time and traditional genres into a new system based on emotional cues and to allow lovers of melancholy music the ability to discover new artists and to quickly immerse themselves in their work. The more I wrote, the more pervasive the theme became. So, heeding the story of Robert Burton (the author of The Anatomy of Melancholy , who spent the better part of a lifetime attempting to chase away his depression and define its scope), and in an attempt to find an ending line, I needed to pull back my scope and focus on only the most important artists and songs.

The book is broken into five distinct aspects: artist profiles, song essays, topic essays, Miserable Lists, and a final list of the top 100 saddest songs of all time. The artist entries are arranged in alphabetical order to foster a sense of discovery, so that readers who may love the National might also chance on Mickey Newbury and a Bright Eyes fan might be tempted to listen to Jacques Brel. There are a handful of song essays scattered throughout to tell the stories of some of the most important songs in the Miserabilist oeuvre, such as Joy Divisions Love Will Tear Us Apart or Billie Holidays Strange Fruit, and topic essays provide coverage of larger umbrella subjects vital to the history and narrative of sad songs, while also serving to broaden the definition of those songs and their meaning to both our culture and our selves. A Miserable List accompanies many of the profiles and essays and are designed to spotlight the saddest material of a given artist or topic.

Finally, the book closes with a list of the top hundred saddest songs of all time. This list is the result of hundreds of hours of listening, contemplating, researching, second-guessing, crowdsourcing, more listening, and editing. Songs have been gathered from all genres across all time, from Josquin des Prezs Mille Regretz to Jhann Jhannssons The Suns Gone Dim and the Skys Turned Black. I have sidestepped full operas, symphonies, song cycles, and other lengthy works that could otherwise be consideredsuch as Sibeliuss Fourth Symphony; Richard Strausss Metamorphosen, Study for 23 Strings ; and Greckis Third Symphony ( Symphony of Sorrowful Songs )in favor of highlighting specific movements, songs, or arias. While performances in English are the focus some songs, such as Jacques Brels Ne Me Quitte Pas, have transcended language and felt appropriate to include. Most notably, to avoid a list overrun by the consistently melancholic catalogs of Cohen, Holiday, Jones, or Van Zandt, only one performance per artist has been included in the top 100 list (though that restriction does not hold with regards to songwriting). Some songs reflect important historical movements and moments, such as the Civil War, the civil rights movement, the residuum of the Vietnam War and, in the twenty-first century, the aftermath of the tragedies of September 11, 2001. Others carry a wider cultural import, such as Taps, which is so tied to tragedy within the American cultural consciousness that its impossible to hear it without also absorbing the historical scarsthe funerals, memorials, and tragediesthat it shepherds. Whether you read the book cover to cover or open it at random, I hope youll find a miserabilist journey as enlightening to interact with as I did in creating it.