Published by Icon Books Ltd., Omnibus Business Centre, 3941 North Road, London N7 9DP

email:

www.introducingbooks.com

ISBN: 978-184831-773-4

Text copyright 2009 Eileen Magnello

Illustrations copyright 2009 Icon Books Ltd

The author and artist have asserted their moral rights.

Originating editor: Duncan Heath

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Contents

Drowning by Numbers

We are drowning in statistics. And they are not just numbers. For the media, statistics are routinely damning, horrifying, deadly, troublesome or, on occasion, encouraging. The press constantly suggest that statistical information about crime, disease, poverty and transport delays is not only the source of the problem, but that it represents real entities or real people instead of one point on a graph.

This tendency to assign meaning to a single essence or example by looking at one point on a statistical distribution creates unnecessary confusion and fear.

Averages or Variation?

Much of the shock-horror statistical information used by the media is based on statistical averages. Despite the often misleading preoccupation with averages, the most important statistical concept neglected by journalists and news reporters is variation. This concept is essential to modern mathematical statistics and plays a pivotal role in biological, medical, educational and industrial statistics.

Variation measures individual differences, while averages are concerned with summarising this information into one exemplar.

So why is variation important?

Variation can be quite easily seen in multicultural Britain, and especially London, which now consists of more than 300 sub-cultures with as many languages spoken (from Acholi to Zulu) and thirteen different faiths. For some, multiculturalism is about valuing everybody and not making everyone the same (or not reducing this ethnically diverse group of individuals to one representative person).

There are so many individual differences across the British population that it is now practically meaningless to talk about the average British person, as one might have done before 1950.

These multifarious individual differences embody the statistical variation that is the crux of modern mathematical statistics.

Why Study Statistics?

Statistics are used by scientists, economists, government officials, industry and manufacturers. Statistical decisions are made constantly and affect our daily lives from the medicine we take, the treatments we receive, the aptitude and psychometric tests employers give routinely, the cars we drive, the clothes we wear (wool manufacturers use statistical tests to determine the thread weave for our comfort) to the food we eat and even the beer we drink.

Statistics are an inescapable part of our lives.

Knowledge of some basic statistics can even save or extend lives as it did for Stephen Jay Gould, whom we will hear more about later.

What are Statistics?

Yet for all their ubiquity, we dont really know what to make of statistics. As one columnist put it, cigarettes are the biggest single cause of statistics. People express a wish to avoid bad things by saying, I dont want to be another statistic. Do statisticians really think that all of humanity is reducible to a few numbers?

Although some people think that statistical results are irrefutable, others believe that all statistical information is deceptive.

My famous dictum, Lies, Damned Lies and Statistics, is often invoked to prove that statistics are quite often deliberately misleading. Lies Dammed lies

Though Twain mistakenly attributed this aphorism to Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli in 1904, Leonard Henry Courtney had first used the phrase in a speech in Saratoga Springs, New York in 1895, concerning proportional representation of the 44 American states.

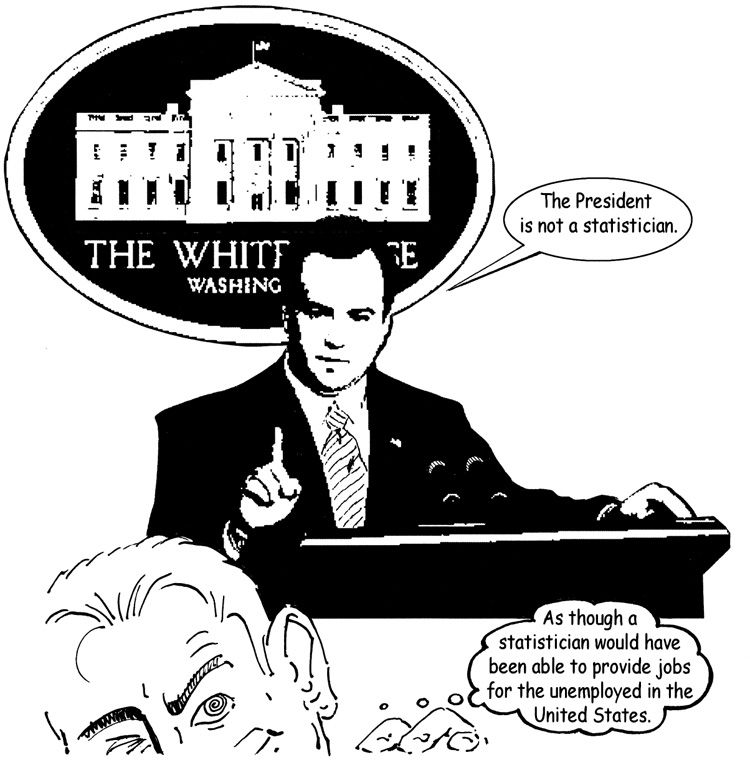

Some government officials even blame statistics for causing economic problems. When White House press secretary Scott McClellan tried to explain in February 2004 why the Bush administration reneged on a forecast that should have led to more jobs in America, his defence was simple.

The President is not a statistician. As though a statistician would have been able to provide jobs for the unemployed in the United States.

In Britain, the Statistics Commission called for Cabinet Ministers to be banned from examining statistical information before it is made public, as this would avoid political influence or exploitation. Nevertheless, the statistics that are available for public consumption can shape public opinions, influence government policies and inform (or misinform) citizens of medical and scientific discoveries and breakthroughs.

What Does Statistics Mean?

The word statistics is derived from the Latin status, which led to the Italian word statista, first used in the 16th century, referring to a statist or statesman someone concerned with matters of the state. The Germans used Statistik around 1750, the French introduced statistique in 1785 and the Dutch adopted statistiek in 1807.

Early statistics was a quantitative system for describing matters of state a form of political arithmetic.

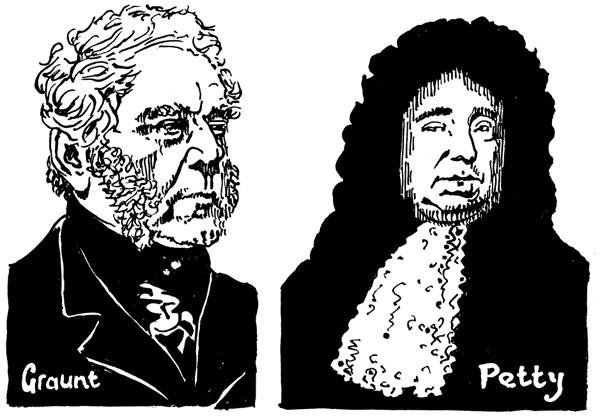

The system was first used in 17th-century England by the London merchant John Graunt (162074) and the Irish natural philosopher William Petty (162387).

In the 18th century, many statists were jurists; their background was often in public law (the branch of law concerned with the state itself).

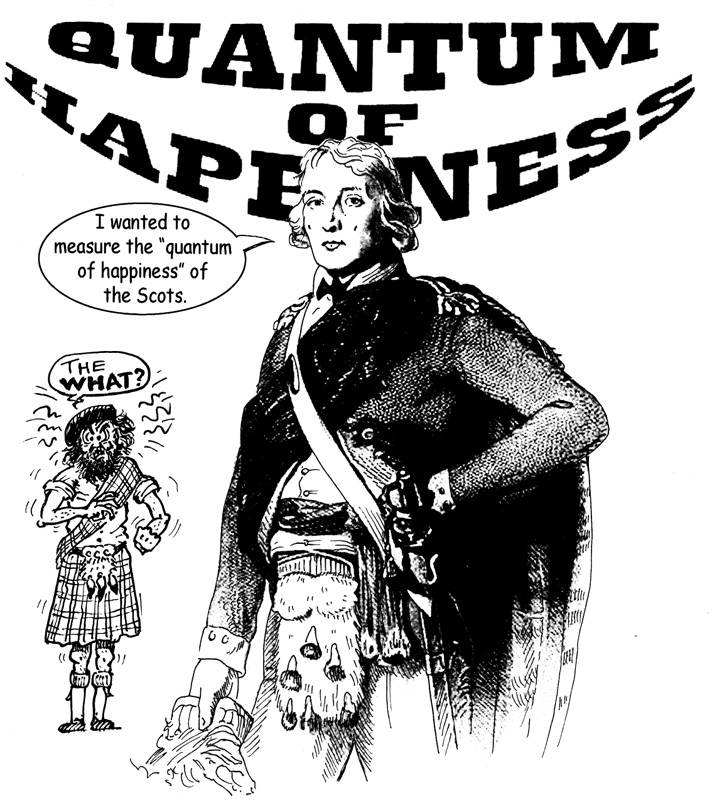

It was the Scottish landowner and first president of the Board of Agriculture, Sir John Sinclair (17541834), who introduced the word statistics into the English language in 1798 in his Statistical Account of Scotland.

I wanted to measure the quantum of happiness of the Scots. The