consent not to be a single being

Black and Blur

FRED MOTEN

DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS DURHAM AND LONDON 2017

2017 Duke University Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

Designed by Amy Ruth Buchanan

Typeset in Miller Text by Westchester Publishing Services

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Moten, Fred, author.

Title: Black and blur / Fred Moten.

Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Series: Consent not to be a single being ; v. [1] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017024176 (print) | LCCN 2017039278 (ebook)

ISBN 9780822372226 (ebook)

ISBN 9780822370062 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 9780822370161 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH : BlacksRace identityUnited States. | African AmericansRace identity. | African diaspora.

Classification: LCC E 185.625 (ebook) | LCC E 185 . 625 .M 684 2017 (print) | DDC 305.896/073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017024176

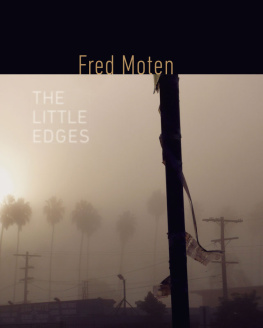

Cover art: Harold Mendez, but I sound better since you cut my throat, 20132014. Digital print transferred from unique pinhole photograph. 20 x 24. Courtesy of the artist.

CONTENTS

The essays in Black and Blur attempt a particular kind of failure, trying hard not to succeed in some final and complete determination either of themselves or of their aim, blackness, which is, but so serially and variously, that it is given nowhere as emphatically as in rituals of renomination, when the given is all but immediately taken away. Such predication is, as Nathaniel Mackey says, unremittinga constant economy and mechanics of fugitive making where the subject is hopelessly troubled by, in being emphatically detached from, the action whose agent it is supposed to be. Indeed, our resistant, relentlessly impossible object is subjectless predication, subjectless escape, escape from subjection, in and through the paralegal flaw that animates and exhausts the language of ontology. Constant escape is an ode to impurity, an obliteration of the last word. We remain to insist upon this errant, interstitial insistence, an activity that is, from the perspective that believes in perspective, at best, occult and, at worst, obscene. These essays aim for that insistence at its best and at its worst as it is given in objects that wont be objects after all.

In its primary concern with art, Black and Blur takes up where In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition leaves off. To celebrate is to solemnify, in practice. This is done not to avoid or ameliorate the hard truths of anti-blackness but in the service of its violent eradication. There is an open set of sentences of the kind blackness is x and we should chant them all, not only for and in the residual critique of mastery such chanting bears but also in devoted instantiation, sustenance and defense of the irregular. What is endowment that it can be rewound? What is it to rewind the given? What is it to wound it? What is it to be given to this wounding and rewinding? Mobilized in predication, blackness mobilizes predication not only against but also before itself.

The great importance of Hartmans work is given, in part, in its framing and amplification of the question concerning the weight of anti-blackness in and upon the general project of black study. It allows and requires us to consider the relation of anti-blackness as an object of studyif there is relation and if it is the objectto the aim of her, and our, work. Any such consideration must be concerned with how blackness bears what Hartman calls the diffusion of the terror of anti-blackness. For me, this question of bearing is also crucial and In the Break is a preliminary attempt to form it. Subordination is not detachment. Disappearance is not absence. If blackness will have never been thought when detached from anti-blackness, neither will anti-blackness have been thought outside the facticity of blackness as anti-blacknesss spur and anticipation; moreover, neither blackness nor anti-blackness are to be seen beneath the appearances that tell of them. The interinanimation of thinking and writing collected here might be characterized as a kind of dualism, but I hope it would be better understood by way of some tarrying with Hartmans notion of diffusion, which is inseparable from a certain notion of apposition conceived of not as therapy but alternative operation.

In my attempt to amplify and understand the scream of Frederick Douglasss Aunt Hester, which he recalls and reconfigures throughout his body of my attempt to study the nature of this uncontainment of and in content. Somehow, in extension of that study, Black and Blur manages to be more preliminary still.

I remain convinced that Aunt Hesters scream is diffused in but not diluted by black music in particular and black art in general. But if this is so it is because her rape, as well as Douglasss various representations of it, is an aesthetic act. Evidently, the violent art of anti-blackness isnt hard to master. My concern, however, is with the violence to which that violent art respondsa necessarily prior consent, an unremitting predication, the practice of an environment that is reducible neither to an act nor to its agent. This brushes up against the question of what the terms diffusion and celebration bear and is, therefore, a question for Hartman, who writes:

Therefore, rather than try to convey the routinized violence of slavery and its aftermath through invocations of the shocking and the terrible, I have chosen to look elsewhere and consider those scenes in which terror can hardly be discernedslaves dancing in the quarters, the outrageous darky antics of the minstrel stage, the constitution of humanity in slave law, and the fashioning of the self-possessed individual. By defamiliarizing the familiar, I hope to illuminate the terror of the mundane and quotidian rather than exploit the shocking spectacle. What concerns me here is the diffusion of terror [Motens emphasis] and the violence perpetrated under the rubric of pleasure, paternalism and property. Consequently, the scenes of subjection examined here focus on the enactment of subjugation and the constitution of the subject and include the blows delivered to Topsy and Zip coon on the popular stage, slaves coerced to dance in the marketplace, the simulation of will in slave law, the fashioning of identity, and the process of individuation and normalization.

In the Break also began with an attempt to engage Hartman; as you can see, I cant get started any other way. What I can say more clearly here than I did there is that I have no difference with Hartman that is not already given in and by Hartman. It is her work, for instance, which requires our skepticism regarding any opposition between the mundane and quotidian, on the one hand, and the shocking and spectacular, on the other, not only at the level of their effects but at the level of their attendant affects as well. Similarly, violence perpetrated under the rubric of pleasure demands our study not just because its commission is in relation to paternalism and property and neurotic stance of the impossible subjectivity that is our accursed share. Against the grain of that stance, which always laments standing from outside of and in opposition to its framework, black art, or the predication of blackness, is not avoidance but immersion, not aggrandizement but an absolute humility.

Hartman writes, with great precision, The event of captivity and enslavement engenders the necessity of redress, the inevitability of its failure, and the constancy of repetition yielded by this failure. tions that cannot be justified? Lets imagine that the latter is true. Then, this absent problem, which disappears in what appears to be inhabitation of the problem of redress, is the problem of the alternative whose emergence is not in redresss impossibility but rather in its exhaustion. Aunt Hesters scream is that exhaust, in which a certain intramural absolution is, in fact, given in and as the expression of an irredeemable and incalculable suffering from which there is no decoupling since it has no boundary and can be individuated and possessed neither in time nor in space, whose commonplace formulations it therefore obliterates. This is why, as Wadada Leo Smith has said, it hurts to play this music. The music is a riotous solemnity, a terrible beauty. It hurts so much that we have to celebrate. That we have to celebrate is what hurts so much. Exhaustive celebration of and in and through our suffering, which is neither distant nor sutured, is black study. That continually rewound and remade claim upon our monstrosityour miracle, our showing, which is neither near nor far, as Spillers showsis black feminism, the ani mater ial ecology of black and thoughtful stolen life as it steals away. That unending remediation, in passage, as consent, in which the estrangement of natality is maternal operation-in-exhabitation of diffusion and entanglement, marking the displacement of being and singularity, is blackness. In these essays, I am trying to think that, and say that, in as many ways as possible.

Next page