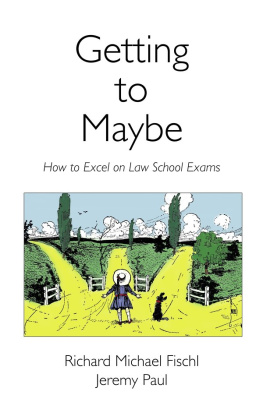

Getting to Maybe

How to Excel on Law School Exams

Richard Michael Fischl

and

Jeremy Paul

Carolina Academic Press

Durham, North Carolina

Copyright 1999

Richard Michael Fischl and Jeremy Paul

All Rights Reserved

eISBN 9781611632170

ISBN 0-89089-760-3

LCCN 99-60901

Carolina Academic Press

700 Kent Street

Durham, North Carolina 27701

Telephone (919) 489-7486

Fax (919) 493-5668

E-mail: cap@cap-press.com

www.cap-press.com

Printed in the United States of America.

For Pam and Laurie

Preface

This book is aimed at every law student who has ever wondered how to progress beyond her teachers repeated warnings that learning the rules is not enough to a sound idea of exactly what it takes to perform well on law school exams. This is no small question. Law students are expected to demonstrate top performance in a setting where everyone agrees that knowing the answer is the wrong way to think about excellence. For most entering law students, however, the obvious alternative to knowing the answer is not knowing the answer. And clearly I dont know isnt what your professors are looking for either. So what lies between getting it right and not getting it at all? What kind of intellectual work is required to cope with exams on which some questions yield yes-or-no answers, but where the real trick is Getting to Maybe?

Both of us wondered about such questions a great deal as we traveled through Harvard Law School many years ago, and neither of us found much guidance beyond the occasional paraphrase of Justice Stewarts famous remark about obscenity, I know it when I see it. So when we began teaching together at the University of Miami in 1983, we decided soon thereafter that we would devote the same level of analytical rigor to the exam process that our colleagues expected us to deploy in our more traditional research. We have been working on this book, off and on and mostly clandestinely, ever since.

We have believed all along that the law school exam is a topic worthy of academic interest. Law professors give the kind of exams they do precisely because they believe that students who perform well have demonstrated the skills identified with good lawyering. So we decided that if we could succeed in providing an accurate description of those skills, we would have helped legal educators everywhere to define more precisely the content of a first-rate legal education.

But we also knew from the start that mere academic concerns would not be enough to spark interest in our work among many in our intended audience. So we have devoted particular care to sharpening observations about exams that we believe will be directly useful to student readers seeking to improve their own performance. We dont believe that any book on exams can substitute for hard work and learning the law. But we are confident that the conscientious student who works through our book will be rewarded at the end of every semester. This is, after all, a how-to book.

What proved most gratifying to us as we progressed with our project was that we discovered no clash between our desire to challenge teachers and students to think seriously about what goes into exams and our goal of helping students write better answers. Indeed, its the combination of these goals that we hope will earn Getting to Maybe a place among the classic books aimed at beginning law students. This is not a book about legal reasoning generally, because its focus is solely on exams. But neither is it a book of simple exam-taking tipsalthough youll find many withinbecause law school exams involve complicated legal reasoning, a fact astonishingly ignored in the many current books that purport to tell students how to write top-flight answers.

What we have done instead is to tackle the exam process by breaking it down into discrete analytical components. Many people describe law school exam questions as hiding legal issues within complicated fact patterns. We compare it with Martin Handford and his wonderful drawings that hide Waldo in a maze of design and color. By watching other people, and practicing on ones own, virtually anyone can get pretty good at locating Waldo. Imagine, however, if you could sit down with Mr. Handford and have him describe for you how he hides Waldo in the first place. Thats our task in Part I of the bookIssues in Living Colorin which we seek to explain why issues (rather than merely chaos and confusion) lurk within those long hypotheticals. We identify aspects of the legal system that create patterned ambiguity where newcomers arrive expecting to find a rulebook instead. Such ambiguity is at the core of law school exams, and virtually every practicing lawyer to whom we have spoken has applauded the idea of figuring out what makes something an issue. Issue recognition, they tell us, is crucial to subsequent success at the bar.

To put Part I to work for our readers, however, we needed to go well beyond merely describing what an issue looks like. We want students to develop study habits that actually fit the skill of spotting issues expected on the typical exam. Like virtually every other guide to exam-taking, this one recommends that our readers study hard, outline their courses, practice on old exams, and discuss the material with classmates. But in Part II, we go beyond the conventional advice to explain how to connect these familiar study techniques to the kinds of performance your professors expect. We hope in the process to vindicate professorial warnings about the dangers of hornbooks and commercial outlines, warnings that too many students ignore at their peril.

Our colleagues often remind us that spotting an issue is only half the battle and that many students fall down when the task turns to analysis. We agree. We doubt, however, that analytical difficulty is a product of students moral or intellectual failings. Rather, we attribute many perceived student inadequacies to a breakdown in communication between students who expect to be judged on whether their answers are correct and professors who want discussion of both sides of difficult questions. So in Parts II and III we seek to remedy the communication gap.

The long, complicated exam question throws many students for one loop and then another. First, because each question contains multiple sources of ambiguity, students must write about how different parts of the law fit together in situations where the student is unsure whether each component of the law applies or not. There is nothing unfair about this. Clients arrive with difficult problems, just as medical patients sometimes end up in an emergency room with more than one complaint. Its hard enough to diagnose a single problemis that pain in the patients abdomen an ulcer, appendicitis, or what? But if the patient has multiple complaints, each with many possible diagnoses, then things get really complicated.

Legal problems are often similarly complex, and exam questions always are. So throughout the book we explore techniques for putting together the many components of a question in ways that will help the student organize and streamline the analysis. Just as the emergency room doctor must learn to focus on which patient complaints are relevant to proper diagnosis, the successful law student must keep her eyes on how each ambiguity in the question will or will not affect the ultimate outcome of a potential legal dispute.

The second way that student expectations are disrupted is a by-product of the first. Questions that pose multiple, interrelated issues will prove extremely frustrating to the student eager to proceed to a result. Once you get a feel for law school, you realize that you should celebrate every ambiguity you see within an exam question because you have that much more to discuss. But in the beginning, as you hurry through to reach conclusions, the temptation is to be annoyed, if not overwhelmed, by all the uncertainty. We show you how you can turn that uncertainty to your advantage by pausing long enough on each of the many ambiguities to provide the kind of discussion your professor wants.