Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

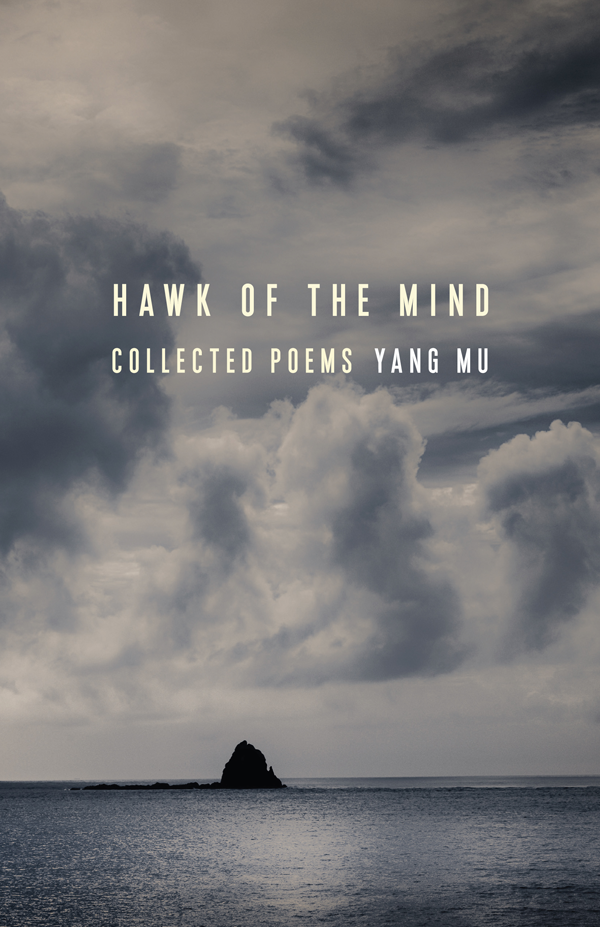

HAWK OF THE MIND MODERN CHINESE LITERATURE FROM TAIWAN MODERN CHINESE LITERATURE FROM TAIWAN Editorial Board Pang-yuan Chi Gran Malmqvist David Der-wei Wang, Coordinator Wang Chen-ho, Rose, Rose, I Love You Cheng Ching-wen, Three-Legged Horse Chu Tien-wen, Notes of a Desolate Man Hsiao Li-hung, A Thousand Moons on a Thousand Rivers Chang Ta-chun, Wild Kids: Two Novels About Growing Up Michelle Yeh and N. G. D. Malmqvist, editors, Frontier Taiwan: An Anthology of Modern Chinese Poetry Li Qiao, Wintry Night Huang Chun-ming, The Taste of Apples Chang Hsi-kuo, The City Trilogy: Five Jade Disks, Defenders of the Dragon City, Tale of a Feather Li Yung-ping, Retribution: The Jiling Chronicles Shih Shu-ching, City of the Queen: A Novel of Colonial Hong Kong Wu Zhuoliu, Orphan of Asia Ping Lu, Love and Revolution: A Novel About Song Qingling and Sun Yat-sen Zhang Guixing, My South Seas Sleeping Beauty: A Tale of Memory and Longing Chu Tien-hsin, The Old Capital: A Novel of Taipei Guo Songfen, Running Mother and Other Stories Huang Fan, Zero and Other Fictions Zhong Lihe, From the Old Country: Stories and Sketches from Taiwan Yang Mu, Memories of Mount Qilai: The Education of a Young Poet Li Ang, The Lost Garden: A Novel Ng Kim Chew, Slow Boat to China and Other Stories Wu He, Remains of Life: A Novel HAWK OF THE MIND COLLECTED POEMS YANG MU EDITED BY MICHELLE YEH COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS New York Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for assistance given by the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange and Council for Cultural Affairs in the publication of this book. Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for assistance given by Mr.

Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New YorkChichester, West Sussex cup.columbia.edu Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press All rights reserved E-ISBN 978-0-231-54561-7 Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from the Library of Congress ISBN 978-0-231-18468-7 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-231-18469-4 (paper) LCCN: 2017040057 A Columbia University Press E-book.

Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New YorkChichester, West Sussex cup.columbia.edu Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press All rights reserved E-ISBN 978-0-231-54561-7 Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from the Library of Congress ISBN 978-0-231-18468-7 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-231-18469-4 (paper) LCCN: 2017040057 A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at . Cover image: Pai-Shih Lee GettyImages Cover design: Chang Jae Lee CONTENTS This book has been years in the making, and it brings me great joy and gratitude to see it in print. From the bottom of my heart I want to thank: Professor Gran Malmqvist, who initiated and has overseen the Yang Mu book series, of which this volume is a part; all the translators for their wonderful contributions and patience; Professor David Der-wei Wang for his unflagging support and friendship; and Mr. Tzu-hsien Tung, generous philanthropist and supporter of Taiwan literature. Id also like to express my deep appreciation to Christine Dunbar and Leslie Kriesel at Columbia University Press for their excellent editing, and to Jennifer Crewe, Associate Provost and Director, and her staff at CUP for shepherding the project from inception to completion. Words cannot express my gratitude for Yang Mu and his wife, Ying-ying.

Not only has his poetry been an inspiration for my own study of modern Chinese poetry for decades, but their trust and friendship have uniquely enriched my life. Michelle Yeh Davis, California AN INTRODUCTION TO YANG MU O angel, if you with your holy glorified mind could not understand these hard-wrought words as blood and tears I pray for your mercy Yang Mu, To the Angel (1993) Ching-hsien Wang, who would later write under the pen name Yang Mu, was born in 1940 in the small city Hualian (also spelled Hualien) on the east coast of Taiwan. Hualian County is best known for its majestic natural beauty, with the Central Range to the west and the Pacific Ocean to the east. It is no surprise that nature plays a significant role in Yangs poetry, not simply as a backdrop but rather as a major source of emotional and spiritual identification. This importance of the natural world is exemplified in the poems Looking Down (1983) and Gazing Up (1995). Written a dozen years apart, they are both set in Hualian and use a river and a mountain, respectively, as their central images.

In the first poem, the poet gazes at the Liwu Stream from precipitous Taroko Gorge and compares his homecoming to a reunion with a woman he loved in his youth. Like the trees and grasses, the middle-aged man with graying hair has experienced much wind and rain, frost and snow. Unlike for nature, however, change for human beings is progressiveand irreversiblerather than cyclical. The returning son is a weathered man, and his relationship with the woman has changed too, as suggested by the juxtapositions of contrasting states of mind: shyness and severity, passion and remorse, adulation and indifference, familiarity and strangeness, acceptance and grievance. The torrential river a thousand meters below evokes tension, not so much between nature and the poet as between his younger self and present self. If these feelings return in the 1995 poem, the mood is notably different.

In Confucianism, mountains and rivers are emblematic of gentlemanly virtues. According to the Master in The Analects , Those who are wise find joy in rivers; those who are benevolent find joy in mountains. The poet who looks down at the Liwu Stream is older and wiser as he comes face to face with his younger self. The poet who gazes up at the Papaya Mountain in the southeastern part of the Central Range experiences great stillness and eternity. Despite the passage of time and the concomitant weathering, despite an equal measure of peacefulness and remorse within, he is reassured and calmed by the mountain, the unchanging symbol of idealism and paragon for emulation. Whereas Looking Down reveals self-knowledge, Gazing Up brings self-reconciliation.

Besides nature, three other major sources of imagery and motifs in Yang Mus poetry are Chinese classics, Western classics, and music. Together they form the core of his aesthetics. Yang Mu began publishing poetry at the age of sixteen, first in his high school journal and in the literary supplement to a local newspaper. Soon he became a regular contributor to Modern Poetry (Xiandaishi), Blue Star (Lanxing), and Epoch (Chuangshiji), three journals of experimental poetry that ushered in the modernist movement in the 1950s and created a golden age in modern Chinese poetry. Yang Mu was among the youngest of the modernists. Writing under the pen name Ye Shan (Jade Leaf), he first became well known for the distinctly Chinese lyricism of his poetry, as manifest in the diction, imagery, and phrasing.

His early poetry teems with images from traditional Chinese poetics, representing both the natural and man-made worlds, like clouds and stars, rivers and hills, fallen flowers, water fountains and fortresses, folding fans, and the Chinese flute. However, those images are used alongside exotic ones evoking foreign places and cultures, ranging from Turkey and Arabia to the green-eyed stranger from Naples, Glorious Provence, and Van Goghs Arles. The fusion of Chinese and foreign elements was, in fact, a salient feature of the modernist movement in postwar Taiwan. Yang Mus engagement in and appropriations of classical Chinese material go beyond allusions and stylistics. He had been an avid reader of Chinese literature, history, and philosophy in college and during postgraduate mandatory military service. This study only grew in scope and depth after 1964, when he came to the United States to pursue graduate education.

Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New YorkChichester, West Sussex cup.columbia.edu Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press All rights reserved E-ISBN 978-0-231-54561-7 Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from the Library of Congress ISBN 978-0-231-18468-7 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-231-18469-4 (paper) LCCN: 2017040057 A Columbia University Press E-book.

Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New YorkChichester, West Sussex cup.columbia.edu Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press All rights reserved E-ISBN 978-0-231-54561-7 Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from the Library of Congress ISBN 978-0-231-18468-7 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-231-18469-4 (paper) LCCN: 2017040057 A Columbia University Press E-book.