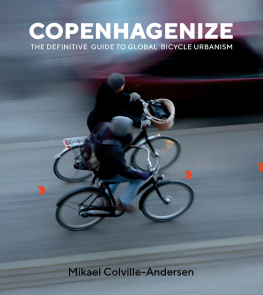

I have spent the past decade staring intently at urban cyclists in cities around the world and closely examining the role of the humble bicycle on the urban landscape and in the finely woven social fabric. All of the thoughts and observations that have welled up through that time have reached a critical mass, and this book, I suppose, is the vessel into which they flow.

In picking up this book, you may have a hunch that Ill be discussing bicycles and bicycle urbanism, and rightly so. Nevertheless, I want to make sure that were on the same page before we begin.

Lets be clear from the get-go. This is a book about bikes, but its also about urbanization. Its about how we possess the ability to move a lot of people through cities and to effectively reestablish the bicycle as a respected, accepted, and feasible transport formall while making money off of the investment.

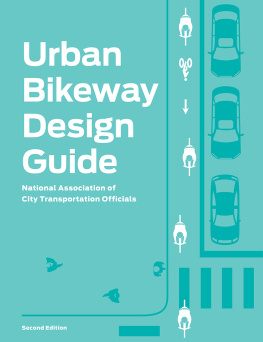

In many culturesnot least in North Americathe bicycle is still sadly misunderstood. It remains a tolerated tag-along in the resplendent urbanism parade. Instead, I will build a pedestal for the bicycle as transport to stand upon, in order to accelerate the understanding of its role in the life-sized city and the transport equation, as well as to drive home once and for all the importance of best-practice infrastructure.

The global bicycle boom has been underway since 2007 and shows no sign of waning. The bicycle is returning as transport in our cities after an absence, in many places, of decades. We have entered into an exciting urban age of rediscovery, but there remains a lack of understanding, be it macro or micro, about the role of bicycle urbanism in our cities as both transport and as a social cohesive. It is high time we fixed that by presenting a clear and definitive guide to the hows and whys of embracing an urban future that includes the bicycle as the key tool for transport, design, planning, and social development. I firmly believe that the bicycle is the single most important tool in our urban toolbox for improving our cities. We need to ensure that as many people as possible are in the loop about how to use it efficiently.

Living in Copenhagenthe City of Cyclistshas offered me a solid pedestal from which I have been able to regard other cities. Through my work I have cycled in over 65 cities around the world, rolling effortlessly along gold-standard infrastructure but also navigating bizarre bike lanes and the worst asphalt imaginable. Studying and analyzing the designs and how they work or dont work. Observing the people cycling in a city and how they interact with the infrastructure or lack thereof, as well as all the amazing anthropological details and transport psychology relating to urban cycling.

Since I am the author of a book about urban cycling and bicycle urbanism, it may come as a surprise that I am not a cyclist. Perhaps quotation marks are in order: cyclist. I dont identify in any way, shape, or form as one. I am just a modern city dweller who just happens to use a bicycle to get around because it is safe and efficient. Ill explore further along why citizens of Copenhagenincluding myselfoverwhelmingly choose the bicycle as transport, but for now it is important to establish that baseline.

When I leave my apartment to go to the bakery, I suppose I become a pedestrian if I walk, a motorist if I take a car, or a passenger if I take public transport. Likewise, I transform from being an apartment dweller to being a cyclist if I hop on my bike. For purposes of gathering data, we get sorted into these categories. Fair enough. The very word cyclist , however, has strong connotations in many parts of the world. If I am talking to someone in a bar in America and I say I am a cyclist, images will invariably appear in their head of me decked out in spandex, helmet, and clicky shoes, out for a long ride somewhere or trying to beat my record for speed or distance. In Denmark, we use the word cyclist to differentiate among traffic users, but very few people will identify as one.

This book isnt about bicycle culture any more than its about vacuum-cleaner culture, which is how I describe bicycle-friendly cities like Copenhagen, Amsterdam, or Tokyo. We all have a vacuum and have learned how to use it. We dont have a stable of vacuums that we keep polished and oiled. We dont dress up in vacuuming clothes or wave at other avid vacuumists on the street. The vacuum cleaner is just an effective tool that makes our daily lives easier. Just like the bicycle.

I came to cycling late. Like any kid, I had a burning desire to learn how to ride, but my dad worked ungodly hours, and while my mum was a model matriarch, her skill set didnt include teaching a kid to ride. I think I was seven when my big brother Steven visited and took me out onto Fairview Crescent and worked with me until I nailed it. Ill never forget that moment. He had been jogging behind me, holding onto the high backrest bar on my banana seatit was the 1970s, manto help me keep my balance. Then, on one run up the street, I realized I couldnt hear his footsteps. I turned my head as best I could and saw him far behind me, standing in the middle of the street with a big smile on his face. I was cycling. Isnt it beautiful how most people remember that moment when they cycle for the first time? Despite decades of car-centric development, children still learn to ride a bike, even if they dont have anywhere safe to ride it afterwards. This remains the first powerful moment of true independence in our lives that we can remember. Were too young to recall sitting, crawling, or walking for the first time, but mastering the bicycle stays with us forever. The fact that learning to ride a bicycle is still a thing is, for me, one of the great poetic aspects of cycling.

I cant be bothered to repair bikes beyond the most basic fixes. Hey, I live in a city with 600 bike shops, so, like most of my fellow Copenhageners, I chuck a bike into a shop for my repairs. But I believe in the bicycle, not only as a brilliant symbol for this emerging urban age but also as the tool for reversing the damage done to our cities over the past century. The bicycle boom that started in early 2007 with Cycle Chic could have been a brief, viral window. A trend like acid-washed jeans in the 1980s (guilty as charged). But the bike stuck. Its as though, without knowing it, we were waiting for its return to fulfill its timeless role as a symbol of modernity.

In 2006, very few cities were considering the bicycle as transport. Ten years on, very few cities havent at least had the conversation, and, more encouragingly, many are making serious efforts to capitalize on bikes.

I grew up in Calgary, Canada, the son of immigrants who had arrived from Denmark in 1953. While much of my childhood and youth was spent on bikescycling to sports, friends houses, and the local shops, and generally disappearing on my bike until I got hungry and came homeI also lived in North America, where getting a car at sixteen was the default. A 15-minute walk to high school became a five-minute drive. No more bus rides to get to the mall. Nevertheless, I still rode my bike, enjoying the pathway around Glenmore Dam and trying to beat the personal best that I had timed.

At eighteen, I moved from Calgary to Vancouver and, for reasons I no longer recall, I would ride my bike from various apartments in North Vancouver to downtown over the Lions Gate Bridge. I just liked it. This was 1986, and I dont remember seeing very many other cyclists on my daily routes. I also recall that I never experienced any animosity from motorists. (Things have changed.)

When, at 22, I ventured farther afieldleaving Canada, never to returnI often found a bike to ride for transport in the cities where I was living. Melbourne, Moscow, London, Paris. Even Suva City and Hong Kong. I was often regarded with curiosity and a bemused smile, but never ridicule. I never wore the spandex uniform of cyclists or had any gear on my trusty 10-speeds. I never intended to be demonstrative about my transport form. I was just a dude on a bike who liked moving around like that.