LANGUAGE AS

BODILY PRACTICE IN

EARLY CHINA

SUNY series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture

Roger T. Ames, editor

LANGUAGE AS

BODILY PRACTICE IN

EARLY CHINA

A CHINESE GRAMMATOLOGY

JANE GEANEY

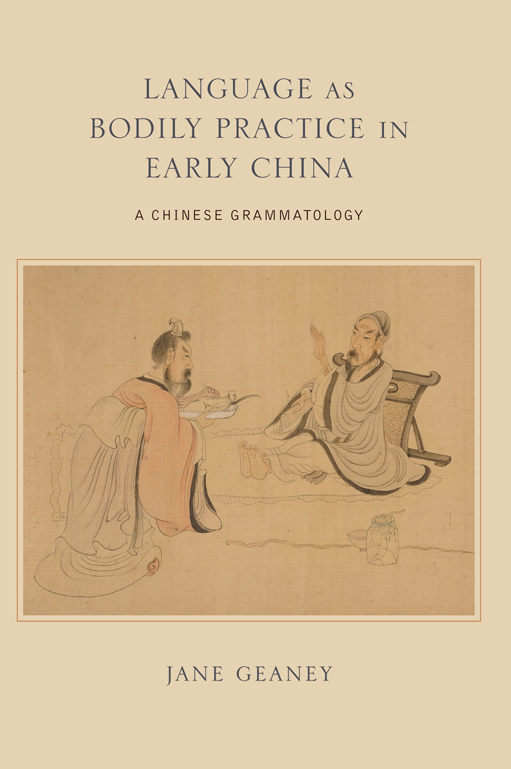

On the cover: Scenes from the Life of Tao Yuanming, detail. Chen Hongshou, Chinese (15991652). Qing dynasty, dated 1650. Ink and colors on silk, handscroll.

11/ 121/ in. (30.3 308 cm). Honolulu Museum of Art Purchase, 1954 (1912.1).

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2018 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Dana Foote

Marketing, Fran Keneston

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Geaney, Jane, author.

Title: Language as bodily practice in early China : a Chinese grammatology / Jane Geaney.

Description: Albany, NY : State University of New York, 2018. | Series: SUNY series in Chinese philosophy and culture | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017015618 (print) | LCCN 2017056108 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438468624 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438468617 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Chinese languagePhilosophyHistory. | Language and cultureChinaHistory.

Classification: LCC PL1035 (ebook) | LCC PL1035 .G43 2018 (print) | DDC 495.109dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017015618

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

P ART T WO

U NDERSTANDING E ARLY C HINESE C ONCEPTIONS OF S PEECH AND N AMES

Acknowledgments

T his book began in 20042005 with research supported by the American Council of Learned Societies and the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation. I have been drawing on the implications of that research ever since. A National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Fellowship in 2012 afforded me time to research and write a chapter and then divide my manuscript into two volumes. The latter, The Emergence of Word-Meaning in Early China: Normative Models for Words, is forthcoming with SUNY Press.

Many people helped make writing this book a rewarding experience. I wish to express my thanks to the staff at SUNY Press who guided me through the editorial process and expertly facilitated the books production: Nancy Ellegate, Andrew Kenyon, Christopher Ahn, Chelsea Miller, Dana Foote, and Fran Keneston. At the University of Richmond, Dean Patrice Rankine provided financial support for the books final phases. The University of Richmond also granted me research funding for several summers.

Ren Songyao and Zhu Pinyan significantly improved this work. Lynn Rhoads was a joy to work with and her professionalism reassured me at every turn. I am very pleased that Nancy Gerth agreed to work on the index.

I am especially grateful to Roger Ames not only for supporting my project but also for inspiring my work. For thirty years Chad Hansen has also informed my thinking in more ways than I can list. I respect and appreciate his genial approach to my disagreements with him.

I am deeply grateful to Dan Robins for reading an early version of the introduction and offering his insights and probing questions about my interpretations. He answered countless emails with precise explanations about Classical Chinese grammar. I am also indebted to Chris Fraser for incisive comments on my work over the years, in this book particularly an early draft of the epilogue. Stephanie Cobb, Mimi Hanaoka, and Doug Winiarski also helped me with the epilogue. Jessica Chan patiently listened to me practice formulating my ideas.

I want to express gratitude to colleagues who, in response to my email queries, offered invaluable information and advice about particular problems, including Michael Nylan, Wolfgang Behr, Joe Allen, Eric Hutton, Gou Dongfeng, and Liu Liangjian. I will always be thankful for the guidance of Anthony Yu, whom I miss, and for all the encouragement he provided during the course of my career.

Finally, I am grateful to my family and friends for putting up with me during the process of writing. I dedicate this book to my parents, Julia and Jack Geaney, for their longstanding love and support.

Introduction

P art of the challenge to understanding ideas about linguistic entities in Early China (ca. 500 B.C.E. to 200 C.E. ) is that even the term language is misleading. If by language we mean a single phenomenon that includes speech, names, and writingthat is, a structure or an abstraction that is manifest in speech and writingthen early Chinese writers were not talking about language even implicitly. I cannot avoid the term, however, at least not in my title, because I will be responding to arguments that take for granted that ideas about language in Early China spawned a crisis. The presumption of a language crisis serves as my hook, which helps me organize various scholars ideas: I strive to argue for an accurate understanding of conceptions of speech and names in early Chinese texts, and the very notion that their presentation of language could foster a crisis presupposes erroneous conceptions. This much will become obvious as I approach the idea of language from an unusual angle: its interaction with human bodies.

The interpretation of language in early Chinese texts that emerges from my investigation is distinctive. Here, the texts do not describe language in relation to a world of sensory experience and mental ideas; rather, early Chinese texts are repeatedly seen to create pairings of sounds and various visible things. In formulating my analysis of early Chinese ideas about language, I resist the impulse to fit it into familiar constructions and instead attempt to account for such pairings by conceptualizing how things related to what we think of as language must have been understood in Early China. That is, by language in Early China, I mean sounds: speech (yan ) and names/naming (ming , ). Language in this sense is more like sounds that issue from the mouth and enter the ears. It is bodily utterances that are emitted and heardnot an abstraction. For some, to describe language as As such, it is within ones control. Thus, people can construct their yan by cultivating their aims, which precede it. They can also develop habits of yan that improve its virtue, in particular, by matching their yan to their deeds, thereby achieving a balance between that which is audible and that which is visible. That is, matching ones yan to ones actions is a form of matching aural and visual, which is an embodied virtue that is to be expected from a sage and from a virtuous person. Hence, when I refer to early Chinese language as a bodily practice, I want to suggest not a performance but something more akin to a technology of the self.

This bodily practice of language differs from more familiar ideas about speech acts in two specific ways. First, early Chinese texts do not discuss phenomena such as a spoken promise making something happen. But in certain contexts, names or naming (ming , ) has the power to make something the case. Unlike