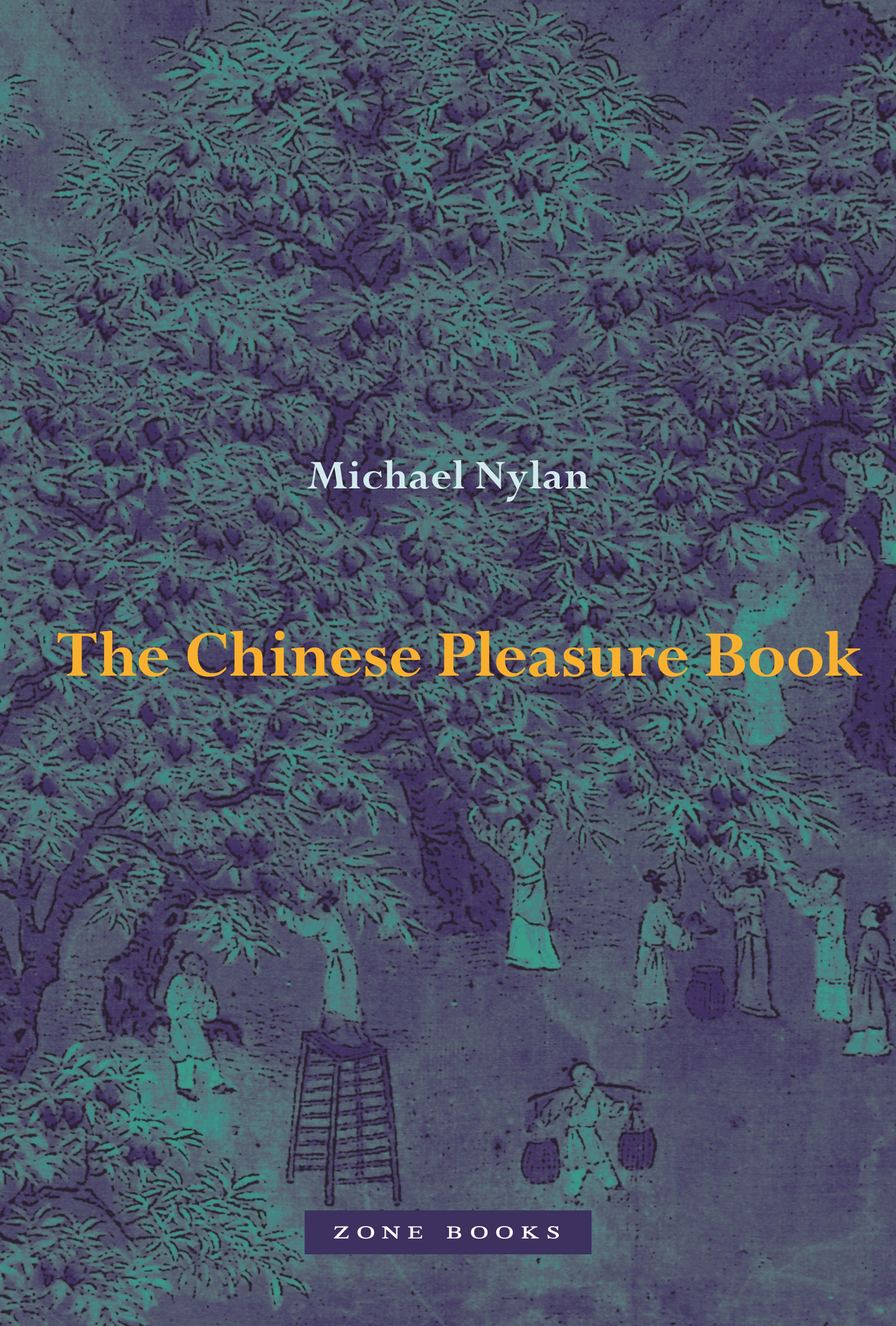

The Chinese Pleasure Book

The Chinese Pleasure Book

Michael Nylan

ZONE BOOKS NEW YORK

2018

2018 Michael Nylan

ZONE BOOKS

633 Vanderbilt Street

Brooklyn, NY 11218

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise (except for that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the Publisher.

Distributed by The MIT Press,

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England

Library of Congress Control No.: 2018015511

eISBN 9781942130161

Version 1.0

To Naomi Richard, une femme formidable

Contents

- 9

- 13

- 17

- 33

- 59

- 135

- 175

- 213

- 261

- 263

- 315

- 317

- 373

- 427

- 429

- 431

- 435

- 439

- Notes and Words Cited may be accessed online at: zonebooks.org/books/133-the chinese-pleasure-book

Preface

When I told my childhood friend that I was writing a book about pleasure-seeking and pleasure-taking, she remarked, Oh, I get it. Youre writing a self-help book. Actually, this is not a self-help book. But readers may certainly treat it as one, if they find that limning the ideas of thoughtful people living in other times and places helps to provoke new thoughts about how to wrest more from life than mere survival. Since the serious dilemmas that people face in living out their days have not changed much, despite huge technological advances, immersing oneself in the questions and answers formulated by very smart people in the past, whether its Zhuangzi or Montaigne (or both), is likely to afford a bit more clarity through useful perspectives. As one philosopher put it, Our perspectives change, largely through what we immerse ourselves in.1 Common tensions in lived experience have been articulated in different ways across cultures, and the differences are fascinating.

I suspect that most Americans associate pleasure with selfishness or worse.2 There is no need to go that route; indeed, every reason not to. One has only to examine carefully the visual and literary tropes in service to modern industries purveying a reckless coupling of blind optimism and individual identity as quasi-autonomy. Against such projects as the Berkeley-based Science of Happiness project, this book contends that a better grasp of social relatedness is basic if we are to figure out how to forge decent lives on the margins of civilizational ruin. While our postmodern preoccupations with representation, virtual reality, and highly mediated existences urge us to avert our eyes, there is profound pleasure to be had from knowing more about the communities we dwell in and how to interact most effectively in them, and there is even pleasure, I would argue, to be had from boldly confronting some unpleasant aspects of experience.3

Several quotations come to mind as I reread the previous sentence. The first, by Van Gogh, identifies the great thing as the ability to wrest new vigor from reality. The second, by Virginia Woolf, says, The future is dark, and that is the best thing for it to be, I think.4 Written decades before Woolfs descent into suicidal depression, Woolfs remark reveals a rather sanguine observation: because we have no chance of foreseeing the future, despair is at once defeatist and irrational. We might as well try to influence our world in humane and sustaining ways. And as the fictional character in a P. D. Jamess novel, Adam Dalgleish, observes, It isnt action but pleasure which binds one to existence.5

It is easy for a historian to act as anthropologist when journeying to lands so distant in time and place as early China, where, not surprisingly, they see things differently. In Shame and Necessity, Bernard Williams (one of the few gods in my academic pantheon) argued that the ethical thinking of the ancient Greeks was in better shape than that of the Kantian and post-Kantian moralists, insofar as the Ancients system of ideas basically lacks the concept of morality altogether, in the sense of a class of reasons or demands which are vitally different from other kinds of reason or demand and where, relatedly, the questions of how ones relations to others are to be regulated, both in the context of society and more privately, are not detached from questions about the kind of life it is worth living.6

The same could be said of the Ancients in early China. For me, it is an article of faith that ongoing conversations with imaginative people, living and dead, are likely to wean me from the usual assumptions. They compel a salutary awareness not only of how peculiar contemporary life is, but also of the verdict that we have never been modern, as Bruno Latour says.7 So while this is no more a book about morality than it is a self-help book, the entire subject of the book concerns the good life and techniques to attain it, the earliest and most insistent topic of the moral question. For these early Chinese thinkers studied ethics in its original sense not as academics, but as skilled questioners looking to spur deeper reflections on the sort of ethos in which to abide.8

With modern science we learn how the world is but not how to live in it, being overwhelmed by the intangible detritus of twenty-first-century life: unreturned emails; unprinted family photos; the ceaseless ticker of other peoples lives on Facebook; the heightened demands of parenting; and the suspicion that well be checking our phones every 15 minutes, forever.9 The writings surveyed in this book attend to the potentially therapeutic: how to create more meaning in our lives while enhancing our vitality, instead of wasting it. Simply put, the group of early thinkers assembled here addressed what Bertrand Russell identified as the central preoccupation of philosophy: how to live without paralysis in a world that knows no certainty.10

Unlike some theories in the modern West, theories proposed in early classical Chinese about the pleasure calculus and attentional economy do not equate rigid control of the self with care of the self, nor do they presume that all things fatigue us at last.11 The Chinese theories did not ever predicate the young child as tabula rasa; the child had inherited proclivities, but the world around her and her own sense of it would modify any earlier tendencies. By the Chinese theories, the whole gamut of the emotions stimulate the sensitive nerve endings in ways that can either soothe and sustain or irritate and drain the energies from the organ systems. Some practices, as a result, support the functions of the body and spirit, while others are liable to endanger it. Yet learning to prefer humaneness to destructive activities that shout power is not always easy. It requires discipline, great teachers, and repeated insights.12

This book tries to make sense of all aspects of living in a constellation of ways deploying a range of methodologies. Inevitably, this book has been designed to trace the classical writers search for meaning. Where this book succeeds, it may, as W. S. Merwin said of his own work, lead you to speculation about the parentage of beauty itself, to which you will repeatedly return.13 When all is said and done, it is the unpredictable contours of humanity, past and present, that intrigue, even enthrall, me as well as how people have long justified their disparate views of humanity. And while caveats will be duly be offered most significantly, for early China, we have little evidence, save that left by a few elite men, most often at court, who are in no way representative of the population at large these texts evince subtle thinking on a human scale, eluding a number of modern pitfalls. I believe they can tell us things.