Nairobis Skyscrapers

Paras Chandaria

Maasai giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis)

Nairobi National Park, Nairobi, Kenya

After reading of plans to build a railway through Nairobi National Park, Chandaria reached for his camera. He photographed the parks animals against the city skyline to show people that wildlife and humans can coexist.

Text copyright 2018 by the California Academy of Sciences.

Photography copyright 2018 by the individual photographers.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-4521-6467-0 (epub, mobi)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN: 978-1-4521-6456-4 (hc)

Designed by Allison Weiner, Jinny Kim, and Rhonda Rubinstein

Chronicle books and gifts are available at special quantity discounts to corporations, professional associations, literacy programs, and other organizations. For details and discount information, please contact our premiums department at or at 1-800-759-0190.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

By Rhonda Rubinstein

By Dr. Sylvia A. Earle

By Suzi Eszterhas

By Dr. Jonathan Foley

foreword by Rhonda Rubinstein

Seeing the Big Picture

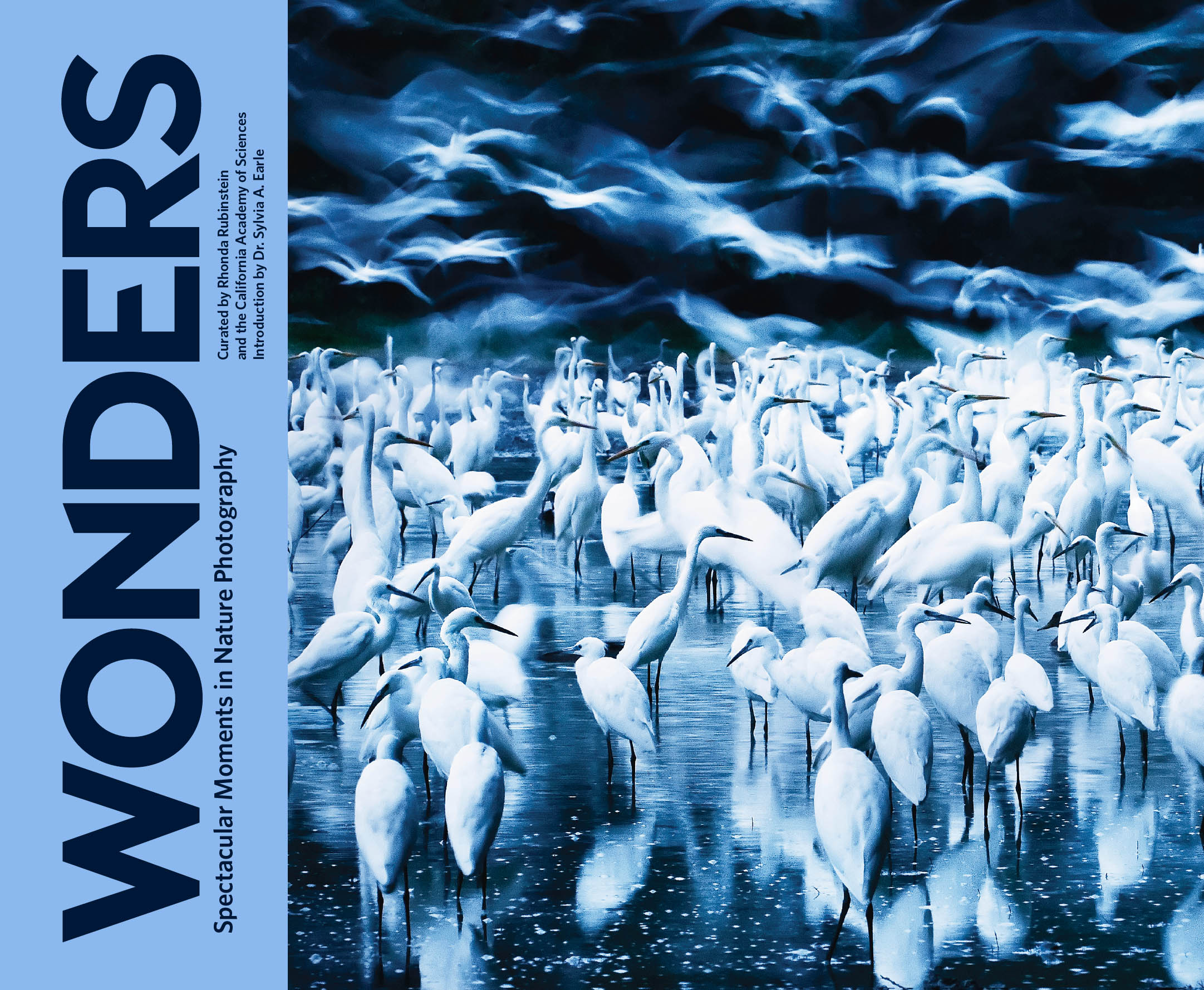

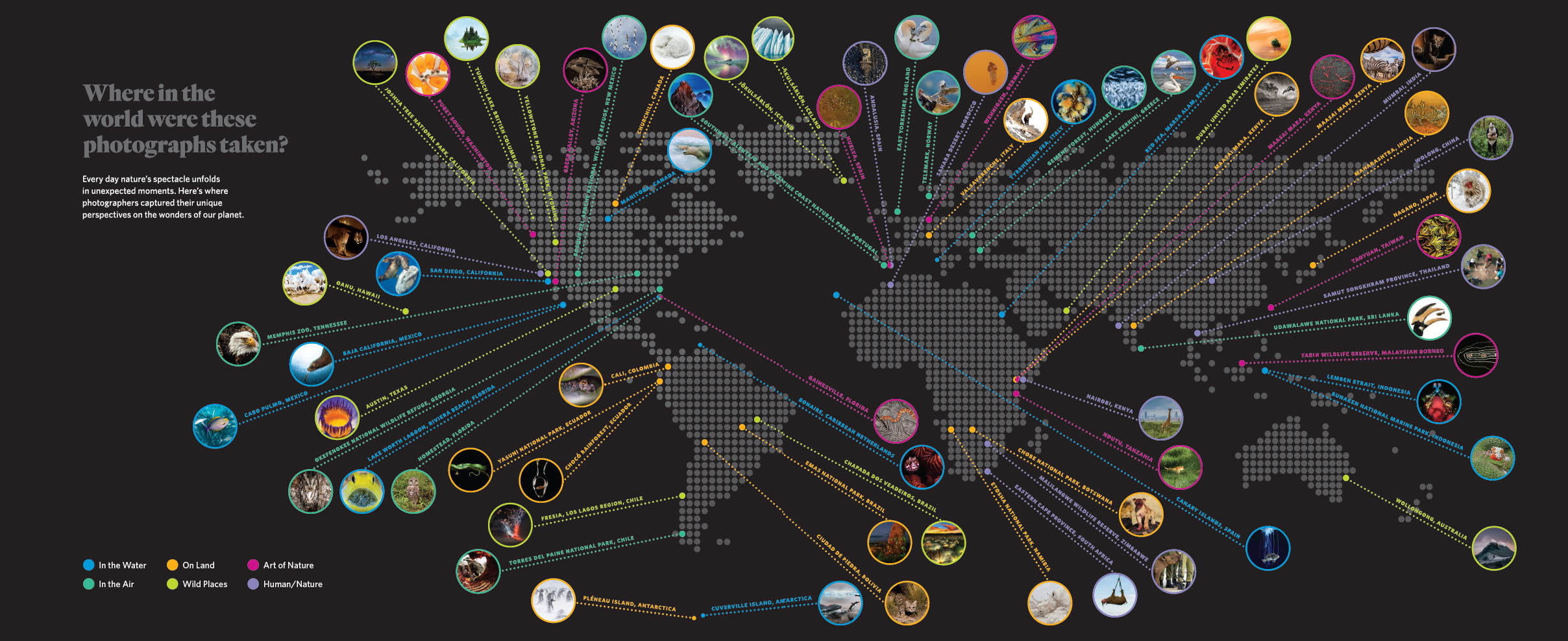

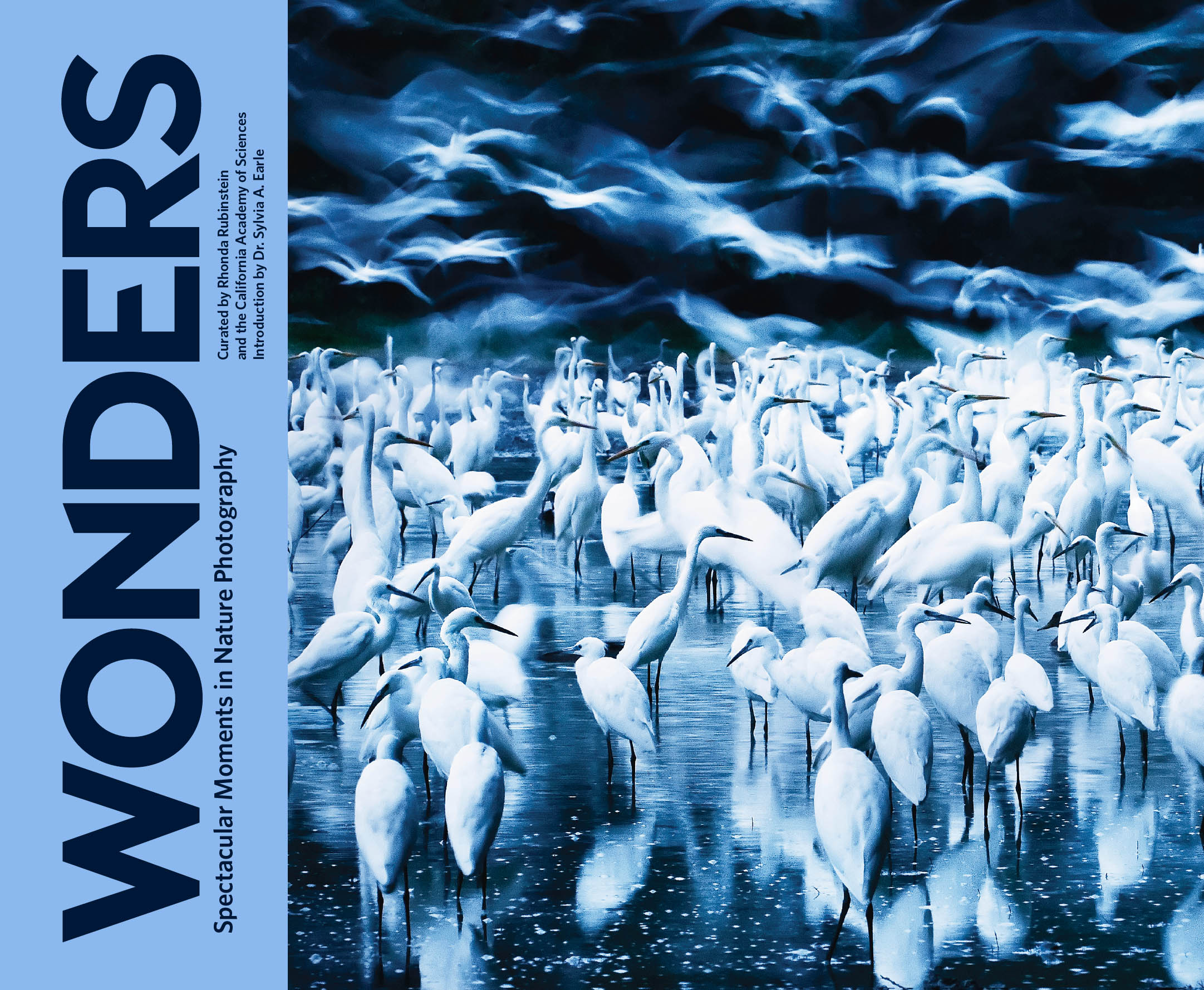

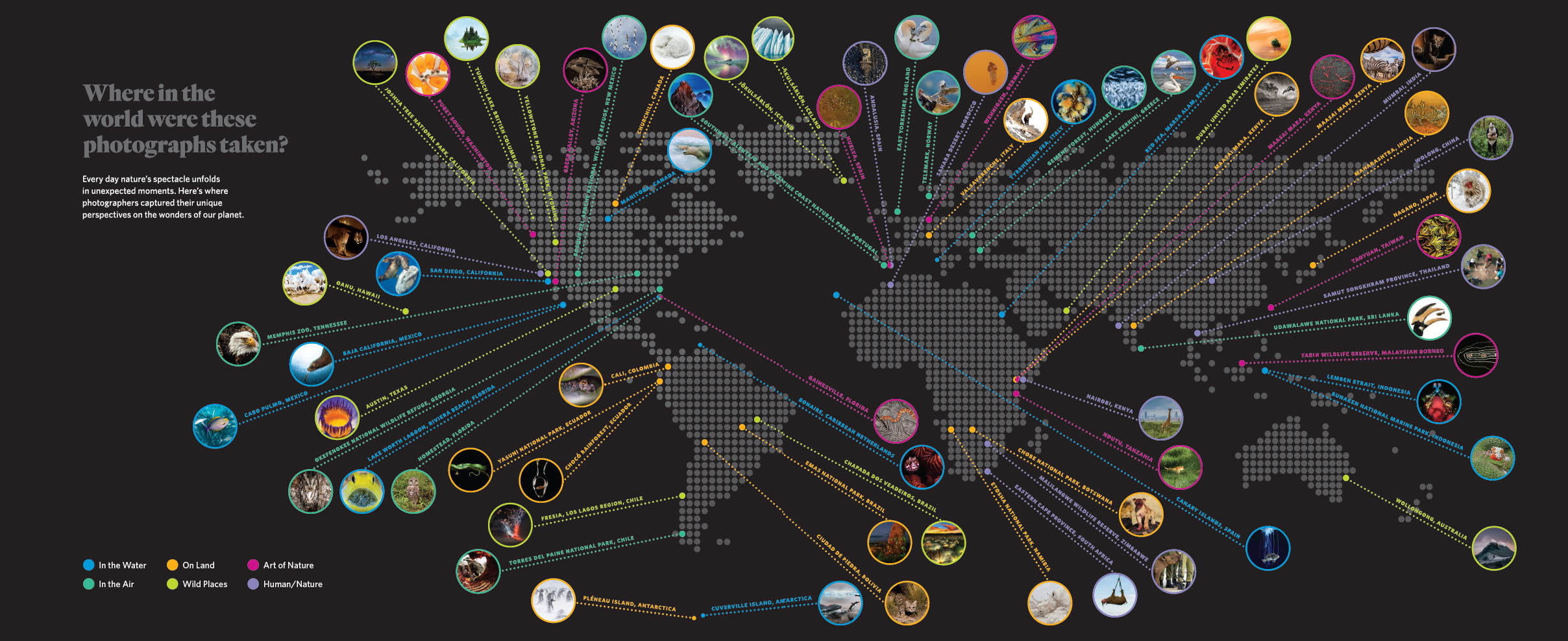

Photographs change the way we see the world. They help us understand a slice of life that wed never considered before. Wildebeests leap off a cliff during the Great Migration. An attacking seal forces a flightless penguin to attempt lift-off. A cougar prowls the night in Hollywood. The photographs in this book remind us that there is a huge, stunning, and still natural world out there, full of striking creatures, bizarre behaviors, and breathtaking landscapes. They show us animals reacting to each other, to the world around them, and to us. They immerse us in the shock and wonder of it all.

Before you sink into the sofa, refreshment in hand, to page through these extraordinary photographs, consider the journey from pixels to page. Nature photographers go, quite literally, to the ends of the Earth, to the places we might never visit, and brave weather and conditions that we avoid, in order to capture a single moment. These adventurous souls wait for hours, if not days, for the bird to return to its nest, the polar bear to emerge, or the skies to clear and reveal the northern lights, without any guarantee of these things actually occurring. To know where and when to wait, the photographers learn as much as possible about the animals and phenomena, using techniques familiar to the scientists who study them. And they are as careful as the scientists not to disrupt what they photograph. Often the photographers aim is to make us care about a creature we didnt even know existed. With luck, they capture that perfect moment.

Back home, days, weeks, or even months later, the photographer selects one or more images from that particular trek to enter into the BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition. We launched this international competition at the California Academy of Sciences in 2014 in order to showcase the amazing diversity of life on Earth and celebrate the photographers dedicated to its preservation. Every year we receive thousands of submissions from hundreds of photographers. To review these, we invite people whose day jobs involve creating, commissioning, editing, distributing, or writing about photographs: a jury of influential photo editors and accomplished photographers from around the globe.

What makes a winning photograph? Our judges select the defining moment in nature, those rare sightings, unusual occurrences, and surprising encounters. They evaluate the composition of forms and natural patterns, shifts of light and focus, and contrasts of color that enhance the drama, surprise, and singularity of the scene.

Remarkable photographs bring the outside inside the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. Photo by Kat Whitney.

The years award-winning photographs are displayed each summer in an acclaimed exhibition at the museum. The images are accompanied by the photographers stories and by Academy scientists perspectives on the less visible context of each photograph. Then the exhibit is gone, disappearing almost as quickly as the moments captured in the photographs. But with this book, and the generosity of the photographers, we can preserve these fleeting moments, these dioramas of light on a printed page, much like the specimens in our scientific collections.

Nature photography is both art and science. Territorial battles, courting rituals, family dynamics, food gatherings, and the movement of multitudes persist as themes in science and throughout the history of art.

As humans who perch nearby on the evolutionary tree, we relate to the dramas depicted in these photographs. They are the great stories of life on Earth, captured in a millisecond, but in the making for millennia.

Rhonda Rubinstein is the creative director of the California Academy of Sciences and cofounder of the BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition.

Dr. Sylvia A. Earle photographs a silky shark in Cuba in February 2017, photographed by Michael Aw.

introduction by Dr. Sylvia A. Earle

Beyond Words

What is Art, monsieur, but Nature concentrated? Honor de Balzac

Late in the 19th century, William Henry Jacksons epic photographs of sweeping landscapes, pristine forests, and wondrous wild animals helped inspire members of the U.S. Congress and President Ulysses S. Grant to establish the nations first national parkYellowstone. People who had never seen a canyon or coyote, let alone a bear or buffalo, began to experience those things vicariously through photographic images, and were inspired to support protection for a growing network of parks and reserves, as well as policies aimed at safeguarding natural, historic, and cultural treasures that might otherwise be forever lost.

Knowing does not guarantee caring, but you cannot care about something if you do not know it exists.

When Jackson began taking and field-processing photographs in the 1800s, his 300 pounds of equipmentcameras, stands, trays, chemicals, glass plates, bags, brushes, and morefilled a wagon. As technology improved, a hearty pack mule was sufficient to support his operations; and in later years, he carried his own gear, a nifty, lightweight 35mm Leica.

My first experience with a camera was with a Kodak Brownie Reflex. It recorded 12 black-and-white, more-or-less in-focus images per roll. Years later, in 1964, I packed a well-worn 35mm Pentax as a vital piece of equipment, chosen to document encounters with people and wildlife during an oceanographic expedition to the Indian Ocean. Keenly aware of the damage salt spray could do to my beloved camera, I watched in horror when one of my shipmates, Frank Talbot (subsequently executive director of the California Academy of Sciences), leaped overboard with an elegant new camera hanging around his neck. I had not yet heard about the breakthrough in designO-ring sealsthat protected the inner workings of Franks Calypso camera, conceived by ocean explorer Jacques Cousteau and later marketed by Nikon in a popular series of pocket-size Nikonos underwater cameras.

Next page