RIVERHEAD BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright 2017 by Steve Casner

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Ebook ISBN: 9780399574115

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Casner, Steve, author.

Title: Careful : a users guide to our injury-prone minds / Steve Casner.

Description: New York, N.Y. : Riverhead Books, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016049067 | ISBN 9780399574092

Subjects: LCSH: AccidentsPrevention. | Safety education. | Public safety. | Industrial safety.

Classification: LCC HV675 .C35 2017 | DDC 613.6dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016049067

p. cm.

Neither the publisher nor the author is engaged in rendering professional advice or services to the individual reader. Neither the author nor the publisher shall be liable or responsible for any loss or damage allegedly arising from any information or suggestion in this book.

Version_1

The first book goes out to the parents.

Thanks for having me.

CONTENTS

Words to Live By

O n the hottest days of a 1960s summer I rode in the back of my grandfathers Chevy pickup truck. Out on the road, I leaned over the side and let the wind blast me in the face. I dont remember if there were any seat belts in the front seat of that truck, but even if it had them, I never saw any grown-ups wear them. We ran around with plastic wrappers over our heads when someone came home from the dry cleaners. We learned about pyrotechnics from experimenting with the ingredients we had in our chemistry sets. I watched construction workers stroll across I-beams stories above me and I could tell that not being afraid of falling made them cool in one anothers eyes. There were seldom guardrails around anything. We had no fancy glass enclosures around our fireplaces. We had kerosene-fueled space heaters that you could kick right over and we sat in front of them on a cold winters night wearing highly flammable clothes. We licked stamps.

If you had asked me then, I might have told you that whatever I was doing was perfectly safe. And if you had asked my grandfather, who was born in 1918, he might have agreed. He saw the popularization of the automobile. When people drove as fast as they dared, sometimes drunk, down streets streaming with pedestrians and children at play. One traffic historian noted that pedestrians, not quite sure what to make of these contraptions we now call cars, would stride right into the street, casting little more than a glance around them. And forget about days spent walking on I-beams a hundred feet up. Coal miners spent even longer work shifts a thousand feet down. When you had a migraine headache, your doctor might have prescribed some hydroelectric therapy, which, as far as I can tell, is a fancy name for tossing a toaster in your tub. Relax, they didnt do this to children. Doctors gave the kids heroin. And when you came down with a case of head lice, they poured gasoline over your noggindecades before anybody got around to nailing the first No Smoking sign to the wall. So forgive me if riding in the back of a Chevy pickup truck as a kid in the 1960s didnt seem all that dangerous. The 1960s were the good old days! Of course, my grandfather would probably say the same thing about the 1920s.

Now that Im all grown up, I have a job, and that job is to worry about our safety. And as fond as anyones memories of the good old days may seem, when I look at the old safety statistics they seem lamentable. If we transported ourselves back to 1918, about one in twenty of us could expect to die as a result of an accident, the popular term for an unintentional but usually preventable injury. Since life expectancy in 1918 was only fifty-two years, unintentional injuries had fewer tries at us before we died of something else. Nevertheless, twenty people is a holiday dinner table. What an eerie feeling that would have been, looking around the table wondering who that one was going to be, if not you.

It didnt take us long to make improvements. Throughout the twentieth century we came up with all sorts of advice about how to be more careful, and it worked its way into our minds, our culture, and even our laws. Look both ways before crossing the street soon became the new careless step off the curb. Indiana became the first state to enact drunk-driving laws, in 1939. The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 aimed to protect employees from known workplace hazards. Some years later, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania outlawed those rides in the back of pickup trucks. Keep out of reach of children severely curtailed kids access to things like plastic bags, toxic chemicals, and sharp objects. The gunpowder that us kids used to whip up with our chemistry sets? Poof. Gone.

The safety tips and advice were accompanied by the invention of safety devices and features on the products we used. Seat belts became standard equipment in passenger cars, and the idea of using them eventually began to click. The palm-and-turn childproof top we still use on pill bottles came along in the late 1960s. Backup beepers on trucks, fences around pools, smoke alarms and sprinkler systems, tip-over switches, impact-friendly surfaces on playgroundsthe good ideas came one after another.

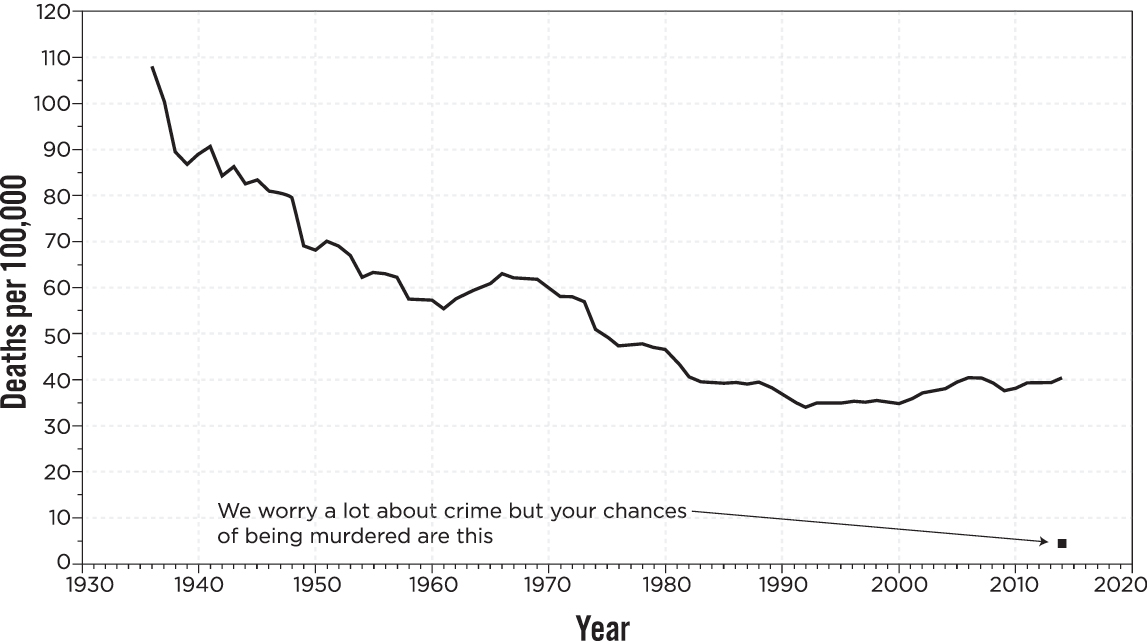

The safety messages and design features made a difference. Look at the progress weve made over the past hundred years in the graph in Figure 1. Thats an impressive decline in the number of fatal injuries. By the time we got to 1992, that one-in-twenty chance of an injury death had dropped to one in fortywhen we were living almost twenty-five years longer, giving the injuries many more opportunities to happen to us. By 1992, you could wager decent money that your whole holiday dinner table was going to make it through life in one piece.

Figure 1: Unintentional-Injury Deaths by Year in the U.S.

But now look what happens after 1992 in the graph. The fatality rate just sort of stayed where it was for the next eight years. And then it started rising again. Its difficult to say with statistical certainty that things are getting categorically worse, but after thirty years, we can say that the impressive gains weve been making since the turn of the century have paused for a historically long time. Today we are back to the safety record we had thirty years ago, and we seem to be stuck with it. (See Figure 2 for how the United States compares to other countries.)