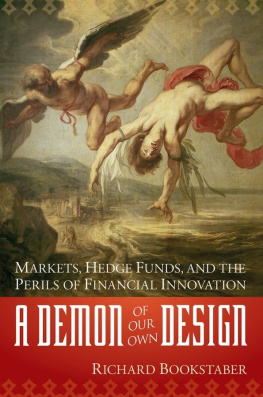

Friday, the thirteenth of October, 1989, had been a quiet day in the stock market; so quiet that some traders went home early. Then around 3 p.m., news broke that a takeover of an airline company had fallen through. The news unleashed a cascade of selling, and by days end the Dow Jones Industrial Average had plummeted 7 percent.

The mini-crash, as it was soon dubbed, has since been largely forgotten. At the time, though, it was rather frightening. It came almost two years to the day after the worst crash in history, Black Monday, and nerves were still raw. That weekend, officials from the Federal Reserve conferred with their foreign counterparts, then put out word that they stood ready to pump money into the financial system. When markets reopened Monday, no such action proved necessary; the Dow quickly recouped half of Fridays drop.

The mini-crash was very much on the minds of the countrys brightest economists when they met the next day at the Royal Sonesta Hotel in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The conference topic was financial crises. Attendees included Ben Bernanke and Mervyn King, future heads of the Fed and Bank of England, respectively, and Paul Krugman, future Nobel laureate. None needed convincing that finance had become more treacherous. The puzzle was why the economy kept humming.

Larry Summers, who would later serve as Treasury secretary to Bill Clinton and adviser to Barack Obama, had a theory. Technological and financial innovation, he told the group, had indeed made finance more bubble-prone. He sketched out a scenario of how a crisis and deep recession could recur. Still, he concluded, since the Great Depression, the federal government had erected firewalls between the financial system and the real economy where ordinary people worked and invested: the vast federal budget, deposit insurance, and, most important, an activist Federal Reserve: It is now nearly inconceivable that there would be no active lender of last resort in time of crisis.

The next panelist, Hyman Minsky, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis, for decades had flogged an iconoclastic theory of business cycles that fellow scholars had largely ignored. Since the 1960s, he said, the authorities had staved off another depression by reacting to every crisis with some combination of government borrowing and Federal Reserve lending. But each success, he warned, simply compounded the behavior that made the system crisis-prone. Success is a transitory phenomenon, he warned. He conceded, somewhat grudgingly, that transitory could last an awfully long time. It had been some fifty years since the last depression.

The last speaker on the panel was Paul Volcker, who had stepped down two years earlier as Fed chairman. He agreed with Summers that the world had more tools for dealing with crises. But his own take was closer to Minskys. He drew attention to a cartoon in that mornings Boston Globe pegged to the Feds promise to pump money into the economy. It portrayed a dollar bill marked United States of Amnesia. We seem to be on something of a hair trigger in using these tools, he observed. This leaves me with the disturbing question of whether by using these tools repeatedly and aggressively we end up reinforcing the behavior patterns that aggravate the risk in the first place.

Twenty years later, we have the answer to Volckers question. The federal government was indeed effective at ironing out the ups and downs of the economy and dealing with periodic financial mayhem; the years from 1982 to 2007 were uncommonly tranquil. But the skill with which the economys overseers had preserved that tranquillity had, as Volcker feared, nurtured risk taking until the stage was set for a devastating crisis.

This has been quite the decade for catastrophe. The world has witnessed not one but two financial meltdowns, one centered in America, the other in Europe. There has been a parade of ever more costly and destructive natural disasters. Much of our hand-wringing has been about all the things we did wrong to bring this on: lax regulation and recklessness in American finance, the political fissures that undermined Europes single currency, mistakes by the designers of the Fukushima power plant or the levees in New Orleans, the role of climate change in the storms, floods, and forest fires whose tolls mount each year.

My story, however, is not about human failure; it is about human successand how that success led to many of those same disasters, and the lessons we should learn from them.

Americas crisis was the result of the twenty-five years of economic stability that came before. The crisis that threatens to break up the euro was possible because of how convinced people were that the euro was permanent. The enormous toll taken by Hurricane Katrina, Superstorm Sandy, and the tsunami that knocked out Fukushima can be attributed to the determination and ingenuity with which engineers and settlers have built cities and livelihoods on the coasts, in the path of water. Levees and other works had been built along the Mississippi as far back as the early 1700s so that its banks and floodplains could be used for settlement, farming, and industry. As a result, when levees fail, more people are flooded. Japan has built seawalls along its coast to protect its cities and industry from tsunamis. This encouraged the growth of population and the siting of nuclear power plants along the coasts. The massive forest fires that now regularly rage across the western United States are due not just to climate change but to how thoroughly forest rangers in prior decades suppressed fire.