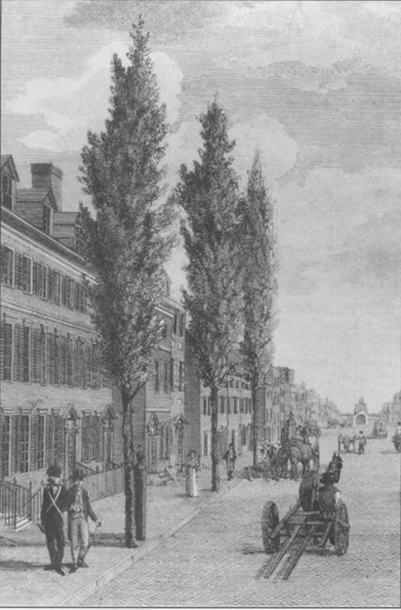

View of Philadelphia in 1798, from the north, along the Delaware.

AMERICAN AURORA

A DEMOCRATIC-REPUBLICAN RETURNS

THE SUPPRESSED HISTORY OF OUR NATIONS

BEGINNINGS AND THE HEROIC NEWSPAPER

THAT TRIED TO REPORT IT

RICHARD N. ROSENFELD

FOREWORD BY EDMUND S. MORGAN

ST. MARTINS PRESS  NEW YORK

NEW YORK

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

THIS WORK IS DEDICATED TO

Poor Richard

and

Young Lightening-Rod

and

Rat-Catchers Who Aspire

to

Their Legacy.

The red-brick townhouses and walking pavements of High-street, also known as Market-street, in Philadelphia, 1798.

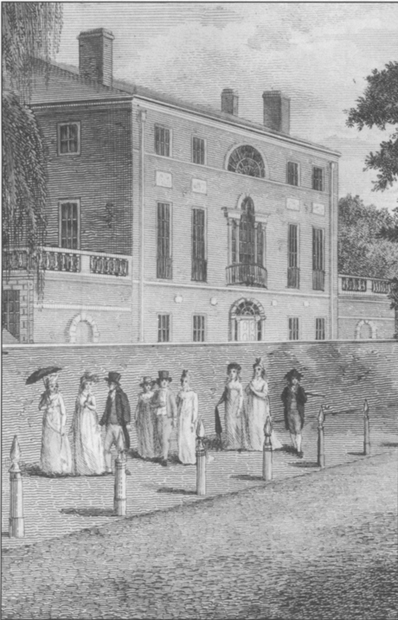

Promenading on Third-street, in Philadelphia, 1798.

Political passions fade with time, leaving their pale shadows to be recovered by historians who usually affect an objective, if not an amused, detachment from them. American politics have seldom generated the fierceness of passion that they did in their first decade. The extravagant exchanges in the contests between Federalists and Republicans in the late 1790s seem today so to exceed the issues as to merit the patronizing dismissal that scholars have generally given them. After all, the nation survived, President John Adams did not secure the crown to which he allegedly aspired, and President Thomas Jefferson succeeded him without bloodshed. Accordingly the dire predictions of tyranny by journalists like Benjamin Franklin Bache and William Duane in their notorious newspaper, the Aurora, have become mere curiosities, extreme examples of the bad manners that political contests so often provoke.

Not so fast, Richard Rosenfeld warns us. He has studied the newspapers and politics of the 1790s afresh and found the issues to justify all the passion they generated. Scorning the usual detachment, he has embraced as his own the outrage of the men who saw the republic threatened by the thrust for power of those entrusted with running it. He stands up for Benjamin Bache, the beloved grandson of Benjamin Franklin, and he literally and literarily becomes William Duane, Baches successor as publisher of the Aurora. He invites us to join him in living through the events that so alarmed these men and to share their alarm in their own words. If we see what was happening as these men saw it, we may emerge with a less complacent view of what it was that the country survived in the 1790s, with a different perspective of what the founding fathers accomplished, even with a new view of who the true founding fathers were.

This is not a typical history, nor does it pretend to be. It is an indictment of some of our customary heroes and a salute to some of our customary villains. It is a piece of historical heresy, written by heretics of the time with the assistance of a kindred spirit who now appeals the sentence of irrelevance that orthodox history has imposed on them. If eternal vigilance is the price of liberty, its vigilant defenders of an earlier time may still have a message for the republic they cherished. That message resounds through these pages.

E DMUND S. M ORGAN

American Aurora was born of some curiosity I had about the Sedition Act of 1798. How, I wondered, could Americas second President, John Adams, possibly signand its first President, George Washington, possibly supporta law that prohibited newspaper criticism of the President? After all, the Bill of Rights, with its guarantee of press freedom, was already seven years old in 1798.

The official answer, I soon learned, was national security. America was preparing for war with France. Press restrictions are upheld in times of war.

Yet something I read greatly troubled me. The Philadelphia Aurora, the principal newspaper that Adams and Washington wanted to silencea paper that reportedly had driven Washington from the presidency the year beforewas being published by Benjamin Franklins grandson (who began the paper shortly after Franklins death). Why, I wondered, would this grandson, Benjamin Bache, want to criticize his grandfathers most famous colleagues? Why wouldnt he want to stand in Franklins shoes?

I was flabbergasted when I read John Adams explanation:

I knew [Benjamin Franklin] had conceived an irreconcilable hatred to me and that he had propagated and would continue to propagate prejudices, if nothing worse, against me in America from one end of it to the other. Look into Baches Aurora and Duanes Aurora for twenty years and see whether my expectations have not been verified.

Did Adams see the ghost of Franklin at the Philadelphia Aurora? Did he want a sedition act, I wondered, to silence Franklins ghost?

I decided to take Adams advice and look into Baches Aurora and his successor William Duanes Aurora to see what old prejudices Franklins ghost was propagating, what old coals Bache and Duane had rekindled that might provoke Adams and Washington to suspend the Bill of Rights, cause them to urge the arrest and prosecution of these editors, incite mobs of their supporters to attack the Auroras offices and to assault and nearly kill these editors, and justify the sacrifice of Baches life and Duanes editorship in hiding.

Heresies! Charges that Washington and Adams were warring against the French Revolution because they were enemies to democracy, and had been even during the American Revolution; that Washington was not the father of his country, but an inept general who would have lost the American Revolution had Benjamin Franklin not gotten France to intervene; that Washington, Adams, Hamilton, and other founding fathers had denied Franklin his credit (partly by understating Frances), had mythologized Washingtons, and had adopted a British-style constitution to avoid Franklins design (and many Americans hopes) for a democracy; and that Adams, Hamilton, and other Federalists really wanted an American king.

The more I read, the more I wondered. The more I wondered, the more I read. Finally, the curtain of time seemed to lift, and I saw the America these editors saw. It was then that I shared their fears.

American Aurora is the story of Bache and Duane, the story of their newspaper, and the story of Americas beginnings that these editors wanted us to know. It is written from Duanes radical Democratic-Republican point of view.

A word about methodology. William Duane, himself an historian, found great difficulty in writing a history of his time. He cited the following:

The epoch of a great revolution is never the eligible time to write its history. Those memorable recitals to which the opinions of ages should remain attached cannot obtain confidence or present a character of impartiality if they are undertaken in the midst of animosities and during the tumult of passions; and yet, were there to exist a man so detached from the spirit of party or so master of himself as calmly to describe the storms of which he has been a witness, we should be dissatisfied with his tranquillity and should apprehend that he had not a soul capable of preserving the impressions of all the sentiments we might be desirous of receiving.

Next page

NEW YORK

NEW YORK