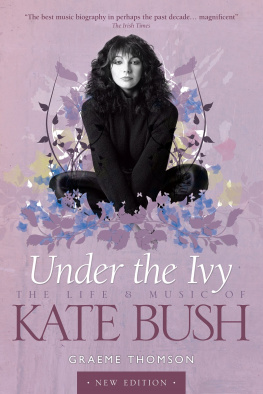

A book of lyrics is a strange beast. Readers who know the songs become hearers as the brain belts out a speeded-up version of the familiar recording, while those readers unfamiliar with the lyrics are confronted by text presented in a poetry format, but which is avowedly not poetry. Poetry is a solo art form: most lyrics need to leave room for, and craft an affinity with, music just as lines in a screenplay must be sparse enough to allow for an actors interpretation. Even in instances where lyrics could pass for poetry to the unwary, lyrics on the page are still a boat in dry-dock, removed from the elements that buoy them and determine their velocity. If quoted aloud, they can be susceptible to spoof: the shadow of Peter Sellers reciting A Hard Days Night in the style of Laurence Oliviers Richard III falls a long way. A book of lyrics, then, begs a question: who would want such a strange beast purring on the bookshelf? Answers will vary.

Mine goes something like, Me; if the lyrics are by one of a small handful of artists whose work has enriched my life and mind over decades. For me, Kate Bush is one of that handful, and I value this perspective on her songs, the way a shipwright would value that dry-dock view of a ship: he or she spots things that a passenger doesnt when the ship is skimming over the waves. To dispense with the metaphors, Ive been a fan for nearly forty years. Being a fan, like being in love, is giddying, its as personal as skin, it connects you with others in a particular way, and it sets you up for a fall. Being a fan puts you on one-way first name terms with the object of your fan-ness, even if he, she, they or Kate dont know you exist as is almost always the case. Over time, the fan-state may change in expression but not in essence.

Fan as a label is a slur on your critical objectivity and even your maturity, but if you werent a fan of something or someone, wouldnt life be a little bland? Bland was a fair description of my first stab at an introduction for this fine Faber collection of Kates lyrics. It focused on Kates use of language and cultural importance, and kept the Kate Bush fan away from my laptop. A few hundred words in, it died of thirst. For this second attempt, then, Id like to look at the lyrics along with my own memories of Kates songs and albums, and my growth from boyhood to fan-hood. By doing so, I hope to shed a little light on why, for millions around the world, Kate is way more than another singer-songwriter: she is a creator of musical companions that travel with you through life. One paradox about Kate is that while her lyrics are proudly idiosyncratic, those same lyrics evoke emotions and sensations that feel universal.

Literature works in similar mysterious ways. Kates the opposite of a confessional singer-songwriter in the mould of Joni Mitchell during her Blue period. You dont learn much about Kate from her songs. Shes fond of masks and costumes lyrically and literally and of yarns, fabulations and atypical narrative viewpoints. Yet, these fiercely singular songs, which nobody else could have authored, are also maps of the heart, the psyche, the imagination. In other words, art.

Pre-YouTube, pre-Spotify, pre-DVD, the predominant TV showcase for pop music was BBC1s Top of the Pops. It began life in 1964 and by the late 1970s a show consisted of thirty minutes of acts from that weeks Top 30 miming their hits to the studio audience, spliced with pop videos and presented by a pair of BBC Radio DJs. To millennials, Top of the Pops may sound as quaint as 1950s radio does to my generation; but most British children of the seventies and eighties will have memories of Thursday evenings in front of the TV, when up to 15 million viewers tuned in. Those of us watching one week in January 1978 saw a video of a ghostly young woman with long black hair, kohl-ringed eyes and red fingernails, dancing her way in a flowing white dress through a song called Wuthering Heights. She mimed the words in a stylised mime-artist manner Id never seen before; and mime-sang in a swooping, delirious, octave-straddling voice that Id never heard. Who was she? What was she? Why did she dance like that? Why were there sometimes two, sometimes three of her? What were those lyrics? A pop song about an Emily Bront novel? At school the following morning all the girls at my small rural primary school were dancing around the schoolyard like twenty Kate Bushes, irrespective of body-shape or size, trailing half-remembered lyrics and clouds of frosted breath.

I remember our headmaster watching from the school steps, his jaw open and his thought-bubble reading, In thirty-five years of teaching, Ive never seen the like of this. Stories of bishops receiving calls from primary schools asking for a mass exorcism sound far-fetched, but fiction can be truer than truth. The following week, Wuthering Heights knocked ABBAs Take a Chance on Me off the singles charts number one perch. Wuthering Heights was the first ever song written by a female artist to top the charts; a female artist, in Kates case, who was only eighteen years old when she wrote it. Other than Top of the Pops, the only ways to access music were the radio, record shops or friends. Then as now, radio was a lucky dip with many more misses than hits.

Buying an actual LP represented a major risk when pocket money was 30p a week and an album cost 5. Understandably, shops had no-returns policies and listening booths had been phased out by my record-buying days. If an album you bought turned out to be a turkey with only one good single on it when you got it home, this was a medium-sized tragedy: you could only buy three or four in a year. Risk encouraged conservatism. You stuck to LPs heard in friends bedrooms; and nobody in my home-taping circle owned either of Kates first two albums, The Kick Inside and 1978s follow-up Lionheart. I heard, and loved, Kates precocious teen-dream The Man with the Child in His Eyes, but had no means to hear it again.

It haunted me for years. I was luckier with England My Lionheart. One night I was listening to DJ Annie Nightingale under the blankets when Kates unmistakable voice came on: I fumbled over to my shoebox-sized cassette recorder, pressed PLAY and RECORD and, by holding the radios speaker against the built-in mike, managed to capture about two-thirds of the song. I was, and am, entranced by this songs Baroque-tinted, concertina-ing of English history, in which a personified, beloved England is Dropped from my black Spitfire to my funeral barge. Nine words encompass five hundred years, and an early example of how time can be compressed or ductile in Kates lyrics. Luckily, my brother had both a three-year advantage in purchasing power, and a fondness for Kate.

He bought the vinyl LP of Never for Ever in late 1980. I pored over its every detail like I would later pore over my first (and last) love-letter. Its cover art was an illustration of monsters and animals streaming out from under Kates skirt, and bore a frisson of the profane, the pagan and Sheela na gig carvings. Its songs were shot through with sounds Id heard rarely or never heard: Prophet synthesisers, a fretless bass, drum-machines, a prismatic vocal stack on Night Scented Stock. The lyrics, too, were like nothing else. Babooshka is a miniature short story about a woman initiating adultery with her own husband.

Delius is her first character study song about the composer, viewed through the lens of his amanuensis Eric Fenbys memoir. Who, prior to 1980, put a song on a pop album about a classical composer? The song Violin is an unruly cousin of The Kick Insides

For Bertie

For Bertie