For Aunt Jo, whose gift of a bookbinding kit set me on my path.

Text copyright 2018 by Anna Marlis Burgard.

Illustrations copyright 2018 by Chronicle Books LLC.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 9781452161648 (epub, mobi)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Names: Burgard, Anna Marlis, author.

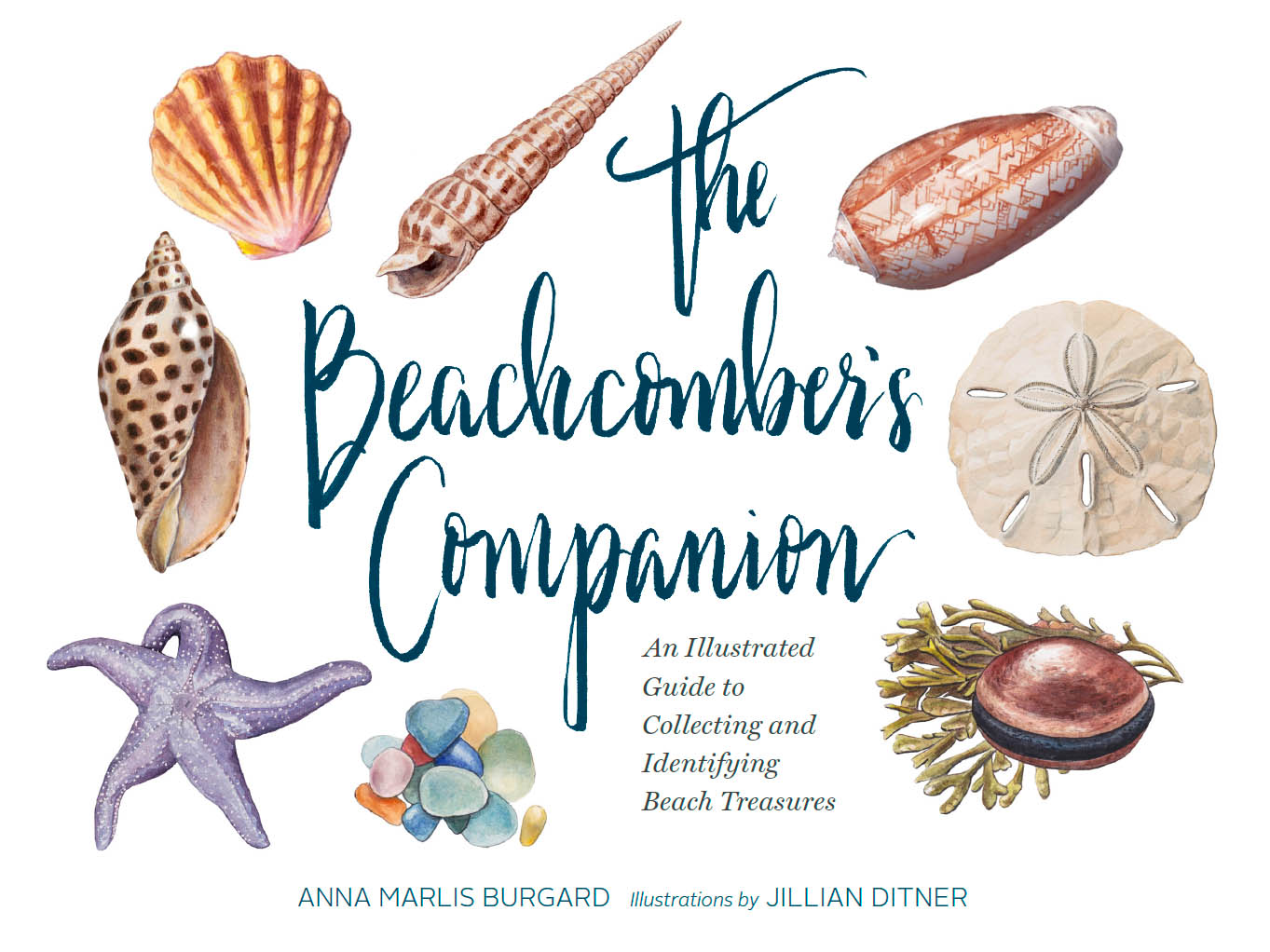

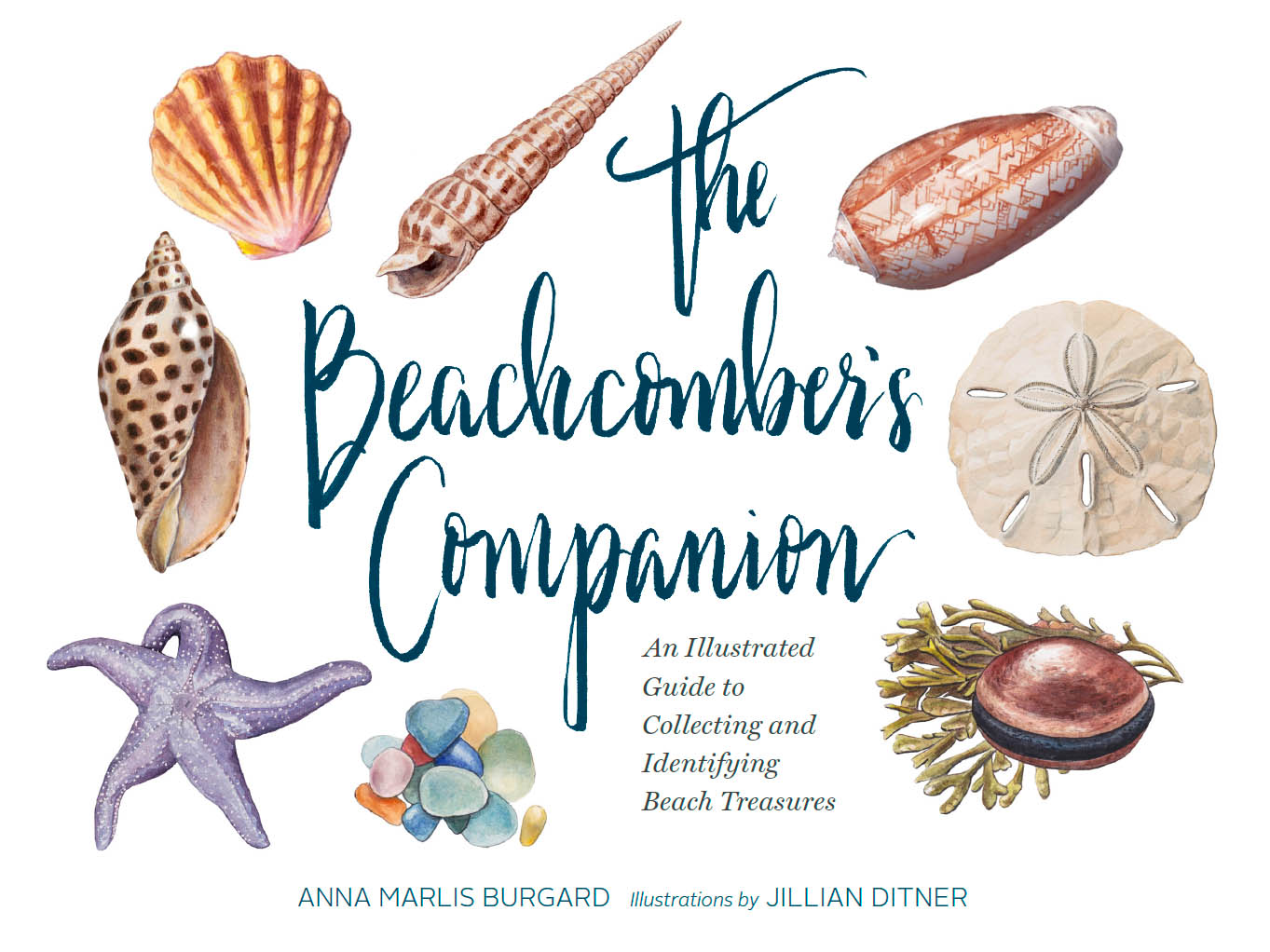

Title: The beachcombers companion / Anna Marlis Burgard ; illustrations by Jillian Ditner.

Description: San Francisco : Chronicle Books, 2018.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017019840 | ISBN 9781452161167 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH: Beachcombing. | ShellsPictorial works. | ShellsIdentification. | ShellsCollectors and collecting. | BISAC: NATURE / Seashells.

Classification: LCC G532 .B87 2018 | DDC 910.914/6dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019840

Illustrations by Jillian Ditner

Design by Jennifer Tolo Pierce

Cover title treatment by Pamela Johnson

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

Contents

Portrait of a Beachcomber

The treasures we find at the beach are all pieces of an oceans story; the shoreline is the introduction where we meet some of its characters and are given clues to its far-reaching communities. Beachcombing is a simple pleasure; the scanning of the surf line, along with the sounds of the waves and wind, helps create a sort of hypnotic state, releasing whatever else might be on our minds. Ancient beach hunters used shells to make tools and ornamental objects some one hundred thousand years ago. Collecting, as we understand it now, existed during the time of the pharaohs, but began on a more widespread basis when the Dutch took to the seas in the seventeenth century. Shells, mainly from Indonesia, rare at that time in Europe, could be more costly than paintings by Vermeer. A true conchylomania set in, driving people to spend outrageous sums to acquire an exotic shell before their friend or competitor had a chance to. Through the Victorian period, curiosity cabinets were filled with praiseworthy specimens; in the last century, diving and trawling gave easier access to once-elusive shells.

Some of historys notable collectors were Emperor Hirohito, Peter the Great, and Fidel Castro. The Smithsonians National Museum of Natural History holds the worlds largest collection, with more than twenty million mollusk specimens. A less grand, but no less passionate, amateur display is found in the Kenneth E. Stoddard Shell Museum in Boothbay, Mainebuilt inside a covered bridgewhich sprang from Stoddards World War II off-duty shell collecting in the South Pacific. Others have created grottoes on their properties with shells (including the famous subterranean chamber in Margate, England), or lined cottage walls with them. Most of us display our shells in much less formal waysin old mason jars and baskets and shadow boxes, or on top of books or along window-sills, but were no less proud of them, or less glad to be surrounded by the memories of finding them.

And of course, beachcombers curiosities are piqued by more than the shells themselveswere also hooked by the stories of the animals that make shells their homes and by our myriad finds environments of origin. An arrowhead unearthed by the Chesapeakes waters on Smith Island, Maryland, connects its finder to a native hunter from the age of mastodons, who shaped it from jasper with a deers antler. A European sea bean collector knows a drift seed traveled thousands of miles on the Atlantics currents from a Costa Rican forest filled with the sounds of scarlet macaws and spider monkeys. A gleaming piece of frosted glass in Seaham, England, began its life as a bottle created by a Victorian factory worker.

Finding a bottle on Turks and Caicos with a message sealed decades before leads to the understanding of a strangers struggle, or perhaps love. And happening upon a coveted junonia shell on Floridas Sanibel Island brings the collector into the life story of a deep-sea creature; people who find them get their photos in the local newspaper.

Beachcombers are excited about true albino shells, about dollhouse-scaled littles, and chuckle about so-called wedding shellsvarieties that arent from surrounding seas but are brought in for nuptial celebrations, leading unaware visitors to believe theyve found a rare shell, half a world away from the waters it called home. For many, the thrill of the hunt alone in a beautiful place is pleasure enough.

It isnt hard to spot us; were the ones who are often more tanned on our backs than our fronts, given how much time we spend bent over looking at things (the Sanibel stoop), poking around in ropes of seaweed wrack and looking into tide pools. Youll see us coming off the beach just as others are starting their morning runs. We head out when everyone else is hunkering down through a tropical storm: we want to see what the churned-up waters will bring ashore, as the turbulence moves deeper shells up over reefs and sandbars and brings floating items from further afield. The lure of wide and deep washes of beautiful objects makes otherwise rational people take risks, including wading into still-ripping currents, with all manner of sharp, heavy shells knocking into our ankles and shins, and waves knocking us down, in what Shellinator Donnie Benton refers to as PowerShelling.

We always know when the tides going out, and we carry extra bags to pick up trash while were moseying along. Were curious, compulsive, and can be a little covetous when someone finds our Holy Grail shell or sea bean or ocean-polished shard of glass. We also tend to be protectors of wildlife, and of their environment, and most of us will stop and tell people anything they want to know about the shell they just picked up (and give them one of ours as a swap if it means saving the live critter theyve unwittingly found). Edward Perry, an avid sea bean collector, talks about the stages that beachcombers proceed through: theres the initial introduction to the seas bounty, followed by studying to satisfy curiosity about the find, followed by hoarding of the treasures, and finally, sharing and swapping to complete a collection. At first, we cant believe our luckthere are so many shells; picking them up is an innocent pleasure. But pretty soon we cover all our surfaces with drying shells, and we start displaying them in various containers, and a sense of feeling filled up by the abundance of them all comes over us. Its alright when we visit the beach for a week or so, but if living by the sea, we can reach a tipping point. To make sure were balancing our wish to build our collection with simply appreciating Mother Nature, we should consider repatriating our less perfect shells or donating them to schools. We should consider those who come behind us to search, and also the ecology of any given beach where that shell might be a hermit crabs next home or the bowl from which a shorebird sips rain.

My beachcombing roots run deep. When I was growing up, my family visited Atlantic islands every year, and as I grew older, I trekked to shores not only in the United States, but also in Europe and Africa. My love for all things ocean eventually led me to found the multimedia project Islands of America: A River, Lake and Sea Odyssey

Next page