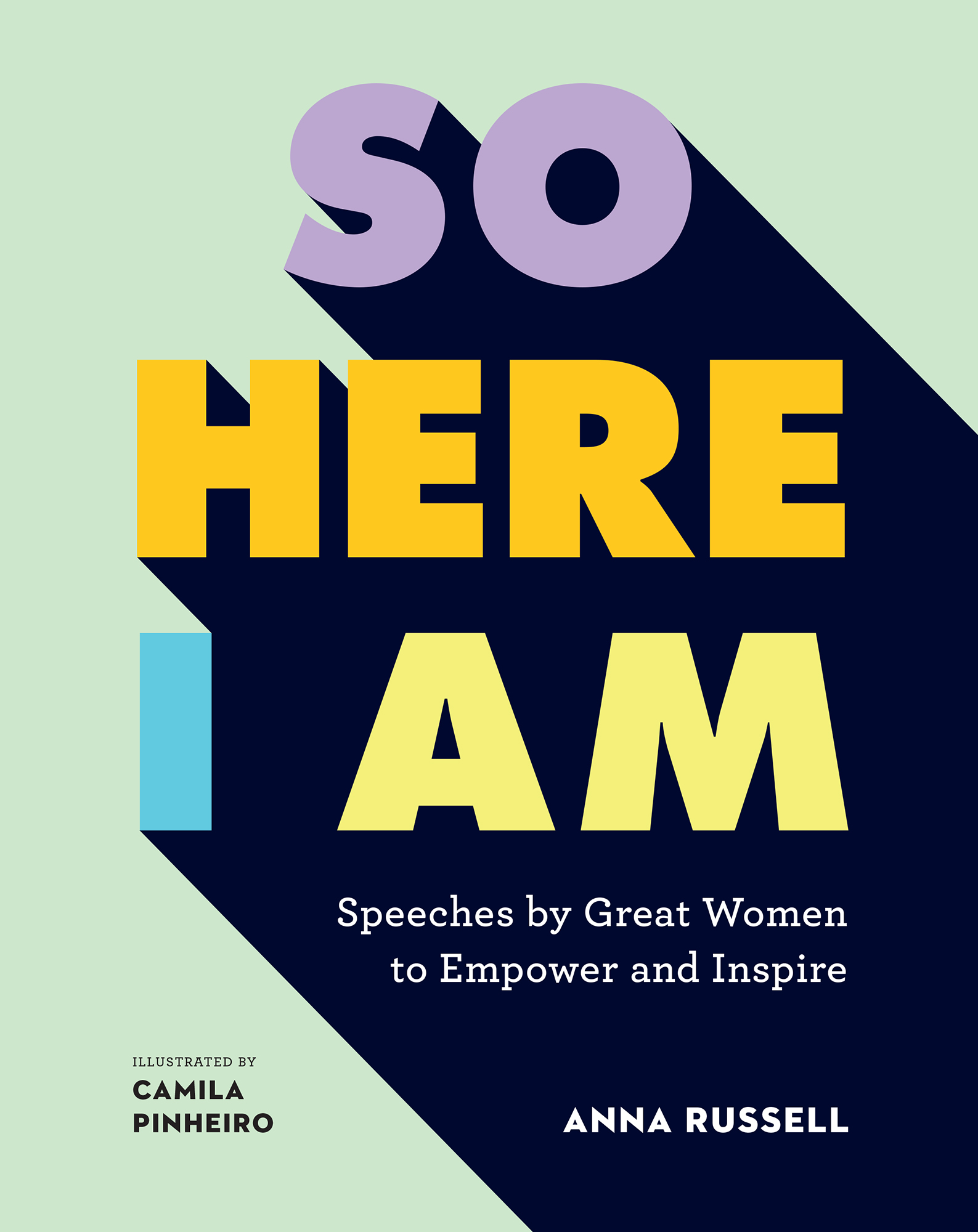

SO HERE I AM

Speeches by Great Women to Empower and Inspire

ANNA RUSSELL

Introduction

Can you think of a speech by a woman?

Thats the question I asked friends and colleagues, family members, former teachers and the occasional unsuspecting stranger, as I started research on this book.

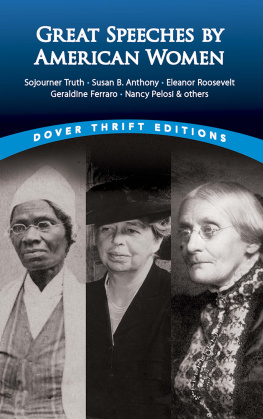

Can you think of a speech by a woman? Id frame it festively, like a trivia question, or a game you might play on a long car ride. It was not a test or a trick; I didnt know the answer. Often, after some thought, the names of a few women would surface, slowly, like bits of silver dredged from the ocean floor, and wed quickly latch on to them. The details were hazy and difficult to make out; the experience was like straining to listen to a conversation being held behind a closed door. Didnt Sojourner Truth say something? wed ask ourselves, sheepishly. What was it that Virginia Woolf expressed so eloquently? And Who was that righteous bonneted lady who made a declaration at Seneca Falls?

In the history of women, many tangible things have been lost to us: posters and petitions; buttons and flyers; private letters and secret diaries; artwork and criticism and literature, appropriated or unsigned for centuries; and an untold number of scrawled lists recording household tasks, doctors appointments, due dates, groceries and funerals. So perhaps its not so surprising that womens speeches are hard to pin down. What, after all, happens to our words after we speak them? Are they scribbled on notepads and transcribed into articles and books? Do they lodge in someones ear, and repeat themselves at quiet moments? Or do they somersault away from our mouths and fade into obscurity?

Early on, I worried that we would not be able to find enough speeches by women to fill a book. One weekend in May, I went to the Brooklyn Public Library and examined a shelf of speech anthologies with serious, reassuring titles: The Penguin Book of Modern Speeches, The Penguin Book of Historic Speeches, American Speeches, Give Me Liberty. This is a treasure trove, I thought. Yet inside the largest collection, The Worlds Great Speeches: 292 Speeches from Pericles to Nelson Mandela (Fourth Enlarged Edition), I found almost as many speeches by men about women, as speeches by women. Former US senator Chauncey Mitchell Depew appeared with a speech titled Woman, the US Civil War officer Horace Porter had Woman! and Mark Twain, in 1882, outdid them both with Woman, God Bless Her. Of 292 speeches, eleven were actually given by women.

In her magnificent history of feminism, The Feminist Promise: 1792 to the Present (2010), Christine Stansell writes of the consequences of historical amnesia for the womens movement; of feminisms tendency towards compulsive repetitions of old mistakes, old arguments, old quandaries. Its as if each generation of women, Ive sometimes thought, coming into their own, and finding the world not as they wished it to be, attacked the same problems as their mothers and grandmothers and even their great-grandmothers without knowing which tools worked and which failed: a kind of perpetual reinvention of the wheel. Often, a new generation has turned on an older one, and, eyes blazing, blamed them for not doing more, without understanding the constraints on those earlier women, who may have been radicals in their own time. How, I wondered, can we still be asking ourselves, after all this thought and stress and study, what it is to be a woman in the world?

From the library, I walked towards the Brooklyn Museum, where Judy Chicagos room-sized installation, The Dinner Party, completed in 1979, is the centrepiece of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. Structured as an enormous triangular banquet table, there is an elaborate place setting for thirty-nine iconic women from throughout history and mythology: Virginia Woolf is there, as is Georgia OKeeffe, Sacajawea, Sappho and Elizabeth I. Beneath the table, on a Heritage Floor, are ceramic tiles painted with the names of nearly one thousand additional women, some familiar, others obscure: Alice Paul, Carlota Matienzo, Florence Nightingale, Catherine II (The Great), Clare of Assisi, Hipparchia, Maria Luisa Sanchez, Rose Mooney, Teresa Villarreal. We dont always think of history in terms of physical space, but Chicagos piece suggests the difficult work of developing a canon of deciding who gets a seat at the table.

In the 1970s, with Womens Studies programmes in colleges still in their infancy, Chicago and her researchers compiled their list of women from haphazard sources, from second-hand books and library catalogues, and by asking each other: an extended network of intelligent, collaborative women (and some men). They were quite literally building the table. By the time I first visited the work, as a curious middle-school student with my parents, over two decades later, the women invited to sit seemed like obvious choices, even a tad too obvious, with reputations beyond dispute. However, the space accorded to women, at a table or in an exhibition or within an anthology, is never without dispute. These are not academic questions: it took some twenty-two years, despite sold-out shows around the world, for The Dinner Party to find a permanent home in a museum.

The transmission of stories about womens lives and choices from one generation to the next is nothing new. It seems likely women have always done it, in private spaces among one another, in gossip or whispered phrases or unsigned work. (In the 1929 essay A Room of Ones Own, Virginia Woolf supposes that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.) Around the time of the French Revolution, women began grappling with the state of their political lives in print; as the British intellectual Mary Wollstonecraft did in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), and as Olympe de Gouges, the French activist and playwright, did in her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen (1791). These were powerful and clear-eyed tracts about womens lot in life; forthright about changes that needed to be made. Still, they were written rather than spoken. The public sphere in many cultures, where lectures and debates took place, was a space reserved almost exclusively for men. At last, in the early 1800s, women, particularly in the United States and the United Kingdom, began speaking out in public about their own condition.

This was a revolutionary act; eggs were thrown, reputations were ruined. In 1829, when the Scottish-born abolitionist Fanny Wright gave an American lecture tour on subjects as innocuous as the importance of education before audiences of both men and women, she was met with scorn, denounced as a prostitute and called a red harlot of infidelity.

Many of the early speeches in this collection come from female abolitionists in the United States, who, speaking out against slavery, soon came to question their own status as second-class citizens. Maria Stewart, an African-American abolitionist, spoke courageously about womens potential as early as 1832. Angelina and Sarah Grimk, the daughters of Southern plantation owners, scandalized their family when they embarked on an anti-slavery speaking tour. In 1838, Angelina gave a passionate speech at Pennsylvania Hall, while an angry mob battered at the doors, and later burned the place down.