INTRODUCTION

O ver hundreds of years wallpaper has been used to decorate the most intimate and personal of the spaces we inhabit the home. The history of wallpaper is the story of changes in fashion and taste, industry and technology, and trade and empire. Thinking about wallpaper is a starting point for thinking about changes in the way we use the spaces in the homes in which we live.

But wallpaper has not always had the attention it deserves. It generally occupies the background rather than the foreground of our lives, but in doing so it can reveal a lot about who we are or who we would like to be. Wallpapers are frequently an expression of personal taste and a way of helping to define personal identity.

Wallpaper has been produced and sold in great quantities in Britain over the past few hundred years. Despite this it is not always easy to find out much about how people actually used it. It is much less permanent than other kinds of furnishings and it does not have the same status as furniture or silverware that can be more easily inherited or collected. Rooms tend to be papered and then re-papered on a regular basis. It is relatively rare to find old photographs or other records that show how wallpaper was used alongside other furnishings. (Even in the twentieth century people did not routinely photograph their own homes.)

When fragments of wallpapers survive in museums they tend to be separated from their context and displayed as art. This book looks at how wallpaper was made and sold and tries to put it back into the context of how it was used in the home. Wallpaper has also been used in commercial and institutional spaces such as hotels and hospitals, but the focus here is on its use within domestic spaces. What do we know about how wallpaper was used in Britain in the past? How was it used to demarcate different kinds of space within the home? This book draws on evidence of wallpaper in museums and stately homes, as well as advertisements and photographs of real domestic interiors.

The history of wallpaper is intimately connected to histories of trade and empire; the American War of Independence affected trade with North America in the eighteenth century, and rivalries with French manufacturers informed British industrial policies in the nineteenth century. As the British Empire spread around the globe, the export of wallpaper helped Britons living abroad to make a house feel like home, even on the other side of the world. Here, though, the focus is on wallpaper in homes within Britain.

Geometric wallpaper patterns such as this were fashionable throughout the 1930s. This paper uses an autumnal tints colour scheme of shades of orange, red, brown and green.

SEVENTEENTH- AND EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY LUXURY

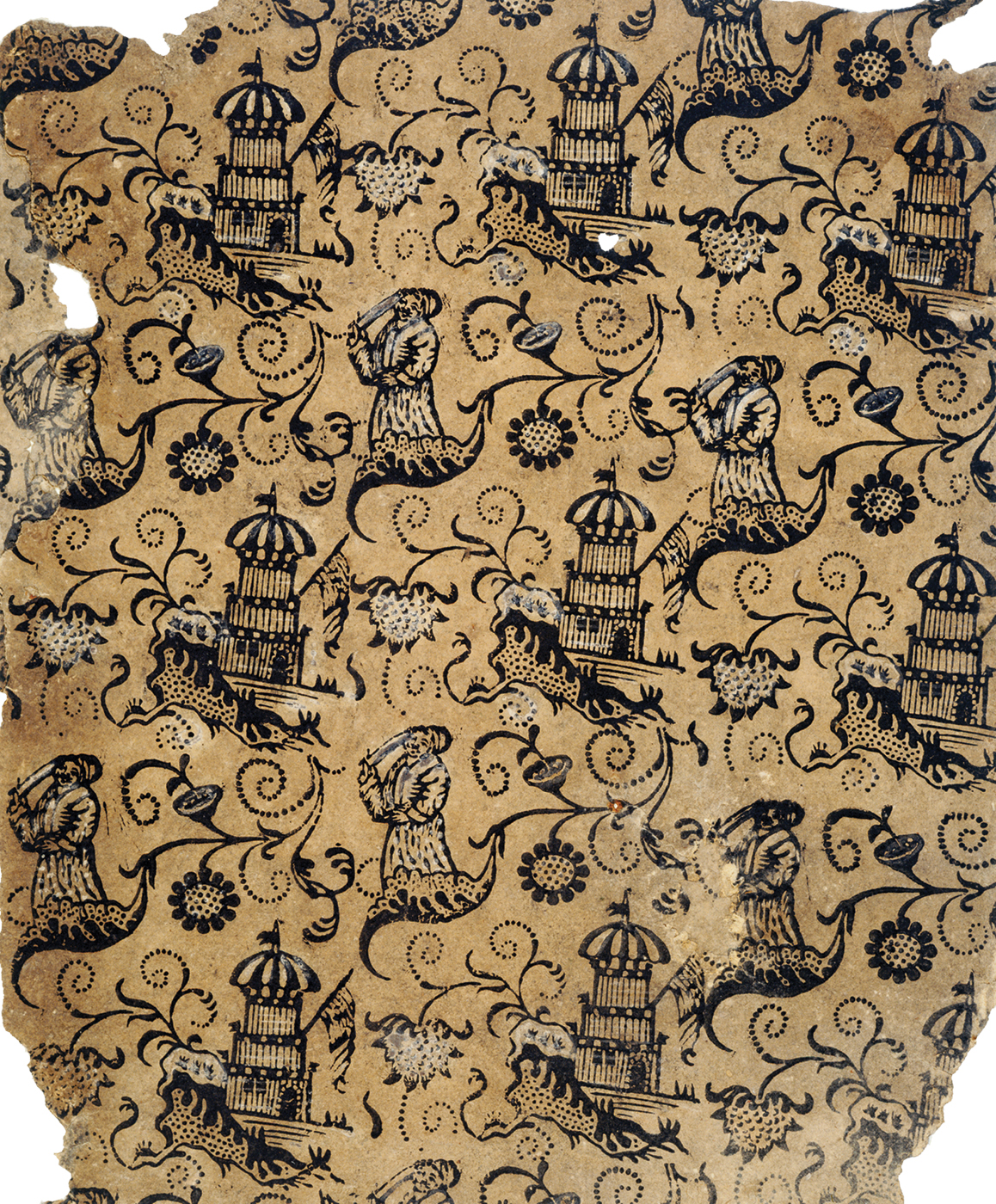

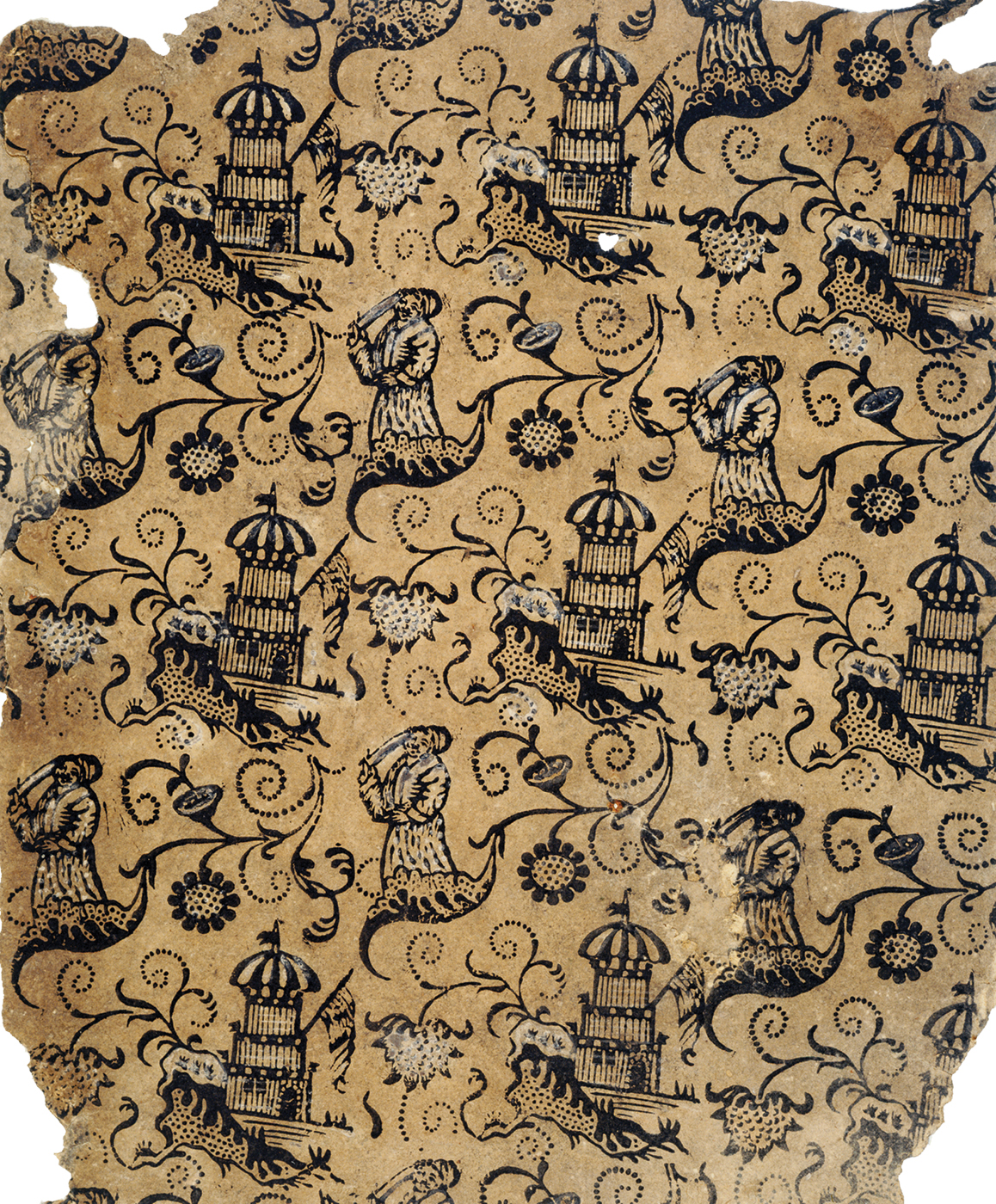

I n the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries wallpaper was expensive because paper could only be produced in small sheets rather than continuous rolls. Printing techniques were not well developed. One of the oldest known examples of wallpaper is a block-printed paper from a house in Lambeth, London, which dates from the 1690s. The house was in Paradise Row, a street quite close to Lambeth Palace.

Wealthy people frequently used textiles such as woven silks and tapestries to decorate their walls. But this was expensive, and throughout its history, wallpaper has been both celebrated and criticised for its ability to imitate other materials, especially textiles. The Paradise Row wallpaper was probably based on a textile design, and was perhaps a more economical way to achieve that effect than using actual textiles.

Flock wallpaper was another kind of paper intended to imitate textiles. To make flock paper the printer would first print a design onto paper with glue, then sprinkle it with finely chopped wool. The wool would stick to the glued areas only, creating an effect similar to a woven silk or velvet. It was a major innovation from around the 1680s and the technique was further improved by the 1740s. The addition of stencilled colour on parts of the pattern could make a flock wallpaper look more like a damask or velvet, and therefore even more impressive. Many of Britains stately homes still contain examples of flock wallpapers that were first hung centuries ago.

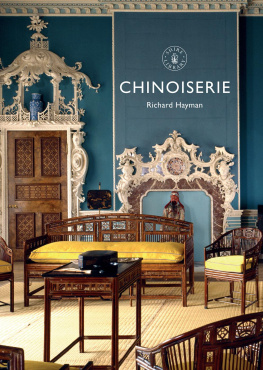

Hand-painted Chinoiserie wallpaper from Marble Hill House in Twickenham, chosen by Henrietta Howard.

The owners of Christchurch Mansion in Ipswich chose a magnificent red flock wallpaper to decorate the State Bedroom in the 1730s or 40s. Another example of flock wallpaper can be found at Ormesby Hall in Cleveland, now owned by the National Trust. Flock wallpapers like these have frequently survived in situ because they were high-quality, luxury products, and were installed in houses that have been preserved over the generations.

This wallpaper from Paradise Row in Lambeth dates from around 1690. The design features oriental figures and exotic buildings in blue on a buff ground.

In the eighteenth century Chinese wallpapers were popular with some of Britains wealthiest people. Chinese wallpapers were first imported by the East India Company in the late 1600s. By the early 1700s, they were frequently paired with other imported products such as Chinese porcelain and lacquer ware to create a whole decorative scheme. Initially the fashion was for painted silks that were hung on battens on the walls. These were gradually replaced by painted or printed papers, which were often large scale and scenic. As Emile De Bruijn points out in Chinese Wallpaper in Britain and Ireland, many of these Chinese wallpapers have survived and can still be seen in Britains historic houses, from Newhailes House in Scotland, to Saltram House in Devon, and many places in between.

Flock wallpaper was used to decorate the dressing room of Ormesby Hall in Middlesbrough. The Georgian mansion was the home of the Pennyman family in the eighteenth century.

Chinese wall hangings frequently featured landscape scenes rather than repeating patterns. Some elements were printed, with detail added by hand. Because of this they occupy a kind of half-way point between paintings and wallpaper. Chinese wallpapers were extremely expensive because they were hand-made by skilled artisans and imported from the other side of the world. Choosing a wallpaper of this kind was a statement of fashionable taste as well as wealth. Henrietta Howard, of Marble Hill House in Richmond, installed a magnificent hand-painted Chinese wallpaper in 1750. This cost 42 and 2 shillings, representing a huge expense. We can get an idea of just how expensive it was by comparison to the annual salary for the households cook, which was only 8 per year.

Block printing was the method most commonly used to print wallpapers in Britain in the eighteenth century. Wallpaper printers, or paper stainers, as they were known, used carved wooden blocks, first dipping them into pigment then pressing onto paper. The blocks generally measured around 24 by 32 inches, and weighed 3040lb (around 15kg), meaning that printers required considerable strength and stamina as well as skill. The techniques were similar to those used to print patterns onto fabrics. Wallpaper making required significant investment of equipment and space to dry the papers after they were printed.