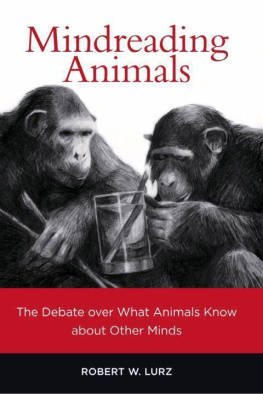

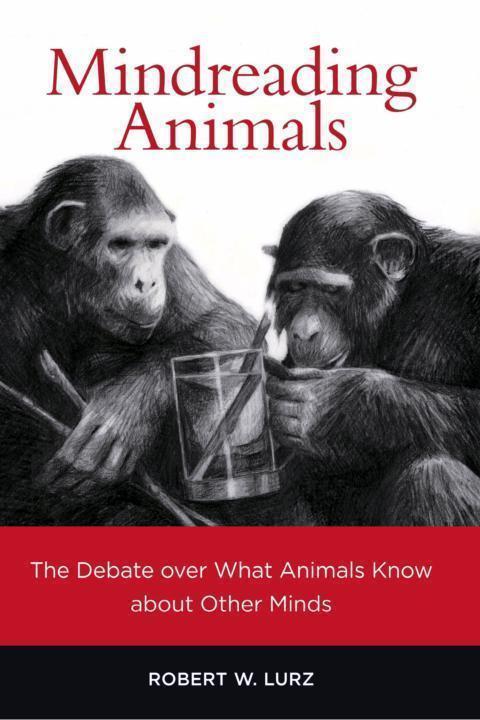

The Debate over What Animals Know about Other Minds

Robert W. Lurz

For Mary Jane, William, and James

Is this a dagger which I see before me,

The handle toward my hand? Come, let me clutch thee.

I have thee not, and yet I see thee still.

Art thou not, fatal vision, sensible

To feeling as to sight? or art thou but

A dagger of the mind, a false creation,

Proceeding from the heat-oppressed brain?

-Shakespeare, Macbeth, act II, scene i

A tactic for embarrassing behaviorists in the laboratory is to set up experiments that deceive the subject: if the deception succeeds, their behavior is predicable from their false beliefs about the environment, not from their actual environment.

-Dan Dennett from "Conditions of Personhood"

Many animals live in a world of other minds. They live and interact with offspring, conspecifics, predators, prey, and owners, many of whom feel, see, hear, intend, know, and believe things (to name but a few states of mind). What is more, animals' well-being and survival often depend critically on what is going on in the minds of these other creatures. However, do animals know this about these other creatures? Do they know or even think that these other creatures have minds? Perhaps they simply see them as mindless, self-moving agents that behave in predictable and sometimes unpredictable ways (e.g., much as we might see the behavior of an ant or a toy robotic dog). How would we know? We cannot, after all, ask them to describe how they think about these other creatures.

The question of whether and to what degree animals know something about other minds has been a hotly debated topic in philosophy and cognitive science for over thirty years now. This book is focused on this debate, and it proposes a way to solve one of its long-standing problems.

I was led to the animal mindreading debate some years ago while working on a series of articles on issues related to animal consciousness, and I quickly became engrossed with its content. It became clear to me, after much study, that there were two fundamental issues that defined the debate: (i) how best to conceive of mental state attribution in animals and (ii) how best to test for it empirically. And I soon became dissatisfied with the answers that philosophers and scientists tended to give to (i) and (ii).

Regarding (i), two approaches to understanding mental state attribution in animals dominated the discussion. Many researchers, influenced by functionalist theories of the mind, assumed that if animals attribute mental states to other creatures, then they must attribute functionally defined inner causal states (sometimes referred to as 'intervening variables') to these other creatures (see Whiten 1996; Heyes 1998; Penn & Povinelli 2007). Another group of researchers, with instrumentalist leanings, argued that all there could be to animals' attributing mental states was the fact that their behavior patterns were usefully grouped and predicted by researchers under the assumption ('stance') that they did (Dennett 1987; Bennett 1991).

I was unconvinced by either of these approaches. Functionalist definitions of our own mental state concepts were notoriously problematic (Nagel 1974; Block 1978; Thau 2002), and so I found it difficult to believe they would do any better at capturing what animals meant by their mental state concepts. And the instrumentalist position struck me as too counterintuitive to take seriously (as well as being incompatible with the kinds of causal explanations that empirical researchers sought to provide with their mindreading hypotheses). After all, whether an animal attributes mental states is surely not something that is determined by someone else's stance-not even a researcher's-any more so than whether you attribute mental states is.

And as for (ii), the kind of experimental protocol generally used to test for mental state attribution in animals (principally, apes) was a type of discrimination task in which the animal was required to choose between two objects (typically, containers) depending on whether another agent in the experiment (usually an experimenter) had or lacked a particular mental state (e.g., saw or did not see the object in question placed inside a container). However, this sort of method for testing mental state attribution in animals struck me, as well as others, as problematic. First, these types of protocols simply could not control for the possibility that, in making their choices between the objects, the test animals were merely using the observable cues that were differentially associated with the other agent's mental state and not the agent's mental state itself. And it became clear that simply adding additional controls to such experiments would not solve the problem. The problem was, as Hurley and Nudds (2006) came to remark, "a logical rather than an empirical problem" for such experimental approaches (p. 63). It was a problem that was solvable only by changing the logic of the protocols used to test for mental state attribution in animals, not by adding further controls to the existing type of protocol. For this reason, this methodological problem has come to be called the "logical problem" in the literature (Hurley & Nudds 2006; Lurz 2009a). A principal aim of this book is to show how this problem might be solved.

In addition, I was suspicious of the fact that these discrimination studies were not directly testing an animal's ability to predict or anticipate another agent's behavior, which arguably is what mental state attribution in animals is designed to help animals do (see Santos et al. 2007). And so I came to agree with Gil Harman (1978) that "[t]he fact that the chimpanzee [or any other animal] makes certain distinctions, no matter how complex, does not show that it has the relevant expectations [of the other agent's behavior] and so does not show that it has a theory of mind" (p. 577). The standard experimental protocol used in animal mindreading research, it seemed to me, was the wrong kind of test to use to elicit mental state attributions in animals. The protocols, rather, should directly test an animal's ability to predict or anticipate another agent's behavior, not its ability to discriminate between objects that only distantly have anything to do with the other agent's mental states.

I therefore came to believe that progress could be made in the debate over mental state attribution in animals by making two substantive changes. First, a bottom-up approach to understanding mental state attribution in animals was needed, one which built a conception of mindreading in animals out of already existing cognitive abilities in animals rather than one that appealed to a preconceived view of the mind deemed applicable to mental state attributions in humans. And second, a new type of experimental protocol was needed that was free from the above problems which beset current experimental approaches, a type of protocol that could solve the logical problem. In a series of papers (Lurz 2001, 2007, 2009a), I began to make a case for these changes, and the current book is the culmination of this progress.