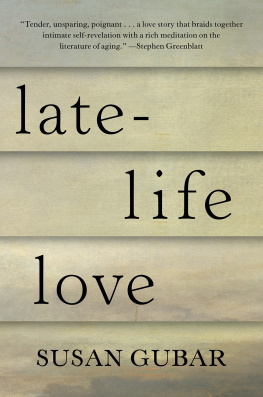

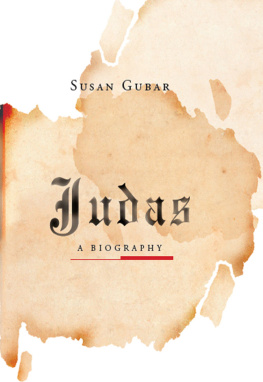

ALSO BY SUSAN GUBAR

Memoir of a Debulked Woman: Enduring Ovarian Cancer

True Confessions: Feminist Professors Tell Stories

Out of School

Judas: A Biography

Lo largo y lo corto del verso Holocausto

Feminist Literary Theory and Criticism

(with Sandra M. Gilbert)

Rooms of Our Own

Poetry After Auschwitz:

Remembering What One Never Knew

Critical Condition: Feminism at the Turn of the Century

Racechanges: White Skin, Black Face in American Culture

Masterpiece Theatre: An Academic Melodrama

(with Sandra M. Gilbert)

MotherSongs (with Sandra M. Gilbert and Diana OHehir)

English Inside and Out: The Places of Literary Criticism

(with Jonathan Kamholtz)

For Adults Users Only: The Dilemma of Violent Pornography

(with Joan Hoff)

No Mans Land, 3 vols. (with Sandra M. Gilbert)

The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women

(with Sandra M. Gilbert)

Shakespeares Sisters: Feminist Essays on Women Poets

(with Sandra M. Gilbert)

The Madwoman in the Attic (with Sandra M. Gilbert)

Copyright 2016 by Susan Gubar

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Ellen Cipriano

Production manager: Louise Mattarelliano

ISBN 978-0-393-24698-8

ISBN 978-0-393-24699-5 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

For those who survive

and

those who do not

Contents

READING

AND

WRITING

CANCER

D O WRITING AND READING about cancer right some of its grievous wrongs? In Reading and Writing Cancer , I answer this question with a resounding yes and then ask: why and how? I believe that engagement with cancer literature and art can alleviate the loneliness of the disease while enhancing our comprehension of how to grapple with it. These convictions arose from recent and not so recent personal experiences.

At the worst times, writing helps us remember. Only the paper napkins handed to me by a nurse enabled me to recall the moment I regained consciousness after the horrific debulking operation that ovarian cancer patients initially undergo. On the paper napkins I recorded my reactions to the rhythm of swabbing and swallowing: a morphine drip had chapped my lips and dried my mouth, and I spent the night with an oddly triangular plastic lollypop, a Styrofoam cup of ice chips... and the mounting pile of napkins. After that botched surgery in 2008 and throughout frightful reoperations and radiological procedures and cycles of chemotherapy, I always carried a pen and pad to record even the less dramatic protocols to which cancer patients are subjected. What would have been lost in a miasma of distress could be retrievedwith the preliminary and scanty jottings.

Although in my previous book, Memoir of a Debulked Woman , I recounted medical treatments that seemed worse than the disease, using my notes and writing the manuscript helped me immeasurably: not only to recall the gruesome events I had endured, but also to serve as a patient-advocate, protesting the so-called gold standard of treatment. More, the process of composition turned out to be as uplifting and inspiring for me as meditation is for others: a way of steadying myself, gaining perspective, quieting anxieties, and shifting my attention from my ailing body to words, to sentences, and (best of all) to the experiences of other people. For between drafting and revising, I avidly devoured accounts composed by men and women confronting different cancers. In illness, Virginia Woolf believed, words seem to possess a mystic quality.

For the past two years, I have been kept alive by a clinical trial and by the New York Times . The regular appearance of my blog, Living with Cancer, has been as life-enhancing for me as the packets of an experimental drug I receive at the Indiana University Simon Cancer Center. Actually, because I have control over the drafting and revising of the essays, they play an even more miraculous role than the pills in revitalizing my existence. This venture has convinced me that writing is an effective complementary therapy for cancer patients coping with the consequences of a ghastly disease.

At the same time, doing research for the blogs has persuaded me that reading the vibrant works of others eases the anxiety of cancer and clarifies what we are going through individually. Now that I have been granted the benefits of a less debilitating targeted drug in a clinical trial, I am able to reflect on these processes. In my absorption with words, I resemble many patient-writers, who have produced journals, poems, graphic memoirs, op-ed columns, sociological books, and performance pieces to challenge and change medical protocols; to help heal, fortify, or renew themselves; and to forge an ongoing cancer canon.

Reading and Writing Cancer explores a unique phenomenon in contemporary times: an explosion of responses to a particular group of diseases not by medical specialists (who have been writing about cancer for centuries) but by patients, caregivers, and artists. For the most part, their work is personally expressive rather than scientific, historical, policy-driven, or polemical. Diaries, essays, memoirs, short stories, and novelsas well as photographs, paintings, movies, television series, and blogsplay a major role today in shaping public understanding of various cancers. Taken together, these productions establish an evolving tradition that has not yet been recognized or charted. I begin by describing writing as a form of therapy and then consider how patients and caregivers, as well as people I am tempted to call civilians or bystanders, have made use of a range of inventive forms that can stimulate and solace us during hard times.

Obviously, writing cannot cure patients, but it facilitates the progress of repairing the damages done. Words have the power to mend spirits abiding within damaged or incurable bodies. Yet some authors of cancer narratives, in thinking about their productions, would undoubtedly object to the term therapy, since it can feel frightening and painful, rather than restorative, to examine the catastrophic repercussions of a cancer diagnosis and its resultant treatments. Like many responding to trauma, such writers would instead describe what they were doing as testifying or bearing witness. Others, especially self-defined artists, might feel that the word therapy erases the rigorous craft involved in framing evocative structures, metaphors, scenes, and arguments to heighten the effect of their productions.

However, therapy is commonly defined as rigorous as well as painful work. Even when engaged in the labor of crafting, or of testifying and bearing witness, cancer patients frequently find that writing about the disease eventually performs a therapeutic function, especially if they have experienced themselves as robbed of who they were before diagnosis or, worse yet, evacuated of any sense of self during treatment.

Surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy can cause patients to feel so invaded, so bombarded, so infused that they lose a sense of their own agency, of subjectivity, even of language. The writing process enables a reconstitution of the selfprobably not the same self that existed before diagnosis, but nevertheless another authentic self and a voice. Be it angry or sorrowful, defiant or resigned, courageous or fearful, this emergent voice helps us understand who we are becoming.

Next page