A GREAT FEAR

ATLANTIC CROSSINGS

Rafe Blaufarb, Series Editor

Gabriel Paquette, Area Editor

The University of Alabama Press

Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35487-0380

uapress.ua.edu

Copyright 2019 by the University of Alabama Press

All rights reserved.

Inquiries about reproducing material from this work should be addressed to the University of Alabama Press.

Typeface: Caslon

Cover image and design: David Nees

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hawkins, Timothy, 1967 author.

Title: A great fear : Lus de Ons and the shadow war against Napoleon in Spanish America, 18081812 / Timothy Hawkins.

Description: Tuscaloosa : The University of Alabama Press, [2019] | Series: Atlantic crossings | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018026900| ISBN 9780817320041 (cloth) | ISBN 9780817392130 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: SpainHistoryNapoleonic Conquest, 18081813. | SpainForeign relations18081814. | Ons, Luis de, 17621827. | SpainColoniesAmerica.

Classification: LCC DP205 .H38 2019 | DDC 940.2/73098dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018026900

For Margaret, Nathan, and Philip

Con todo mi amor...

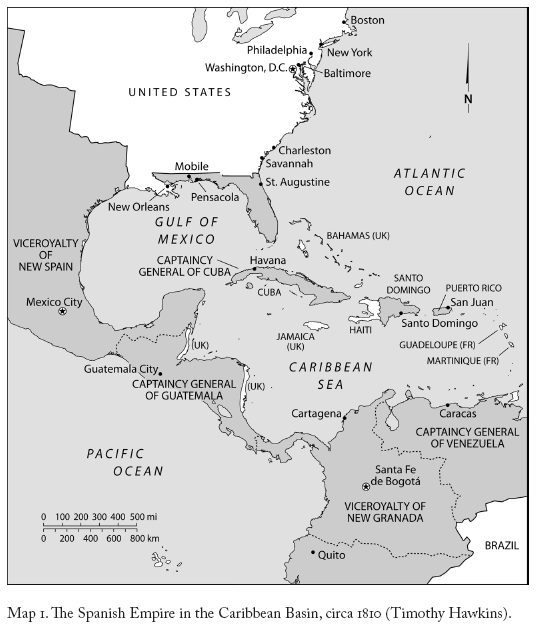

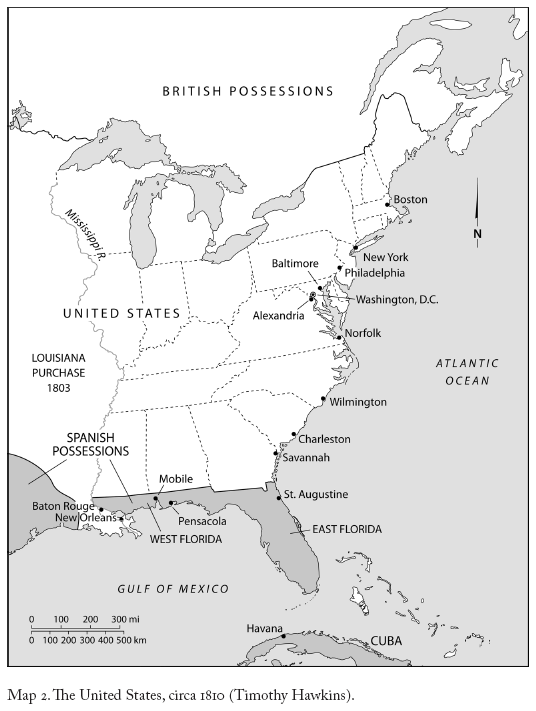

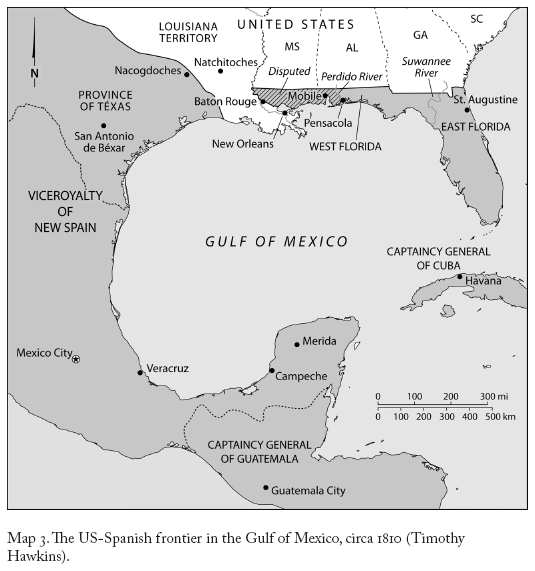

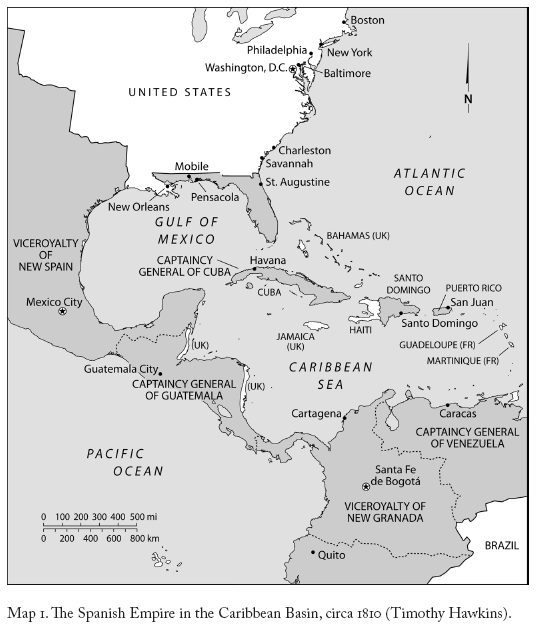

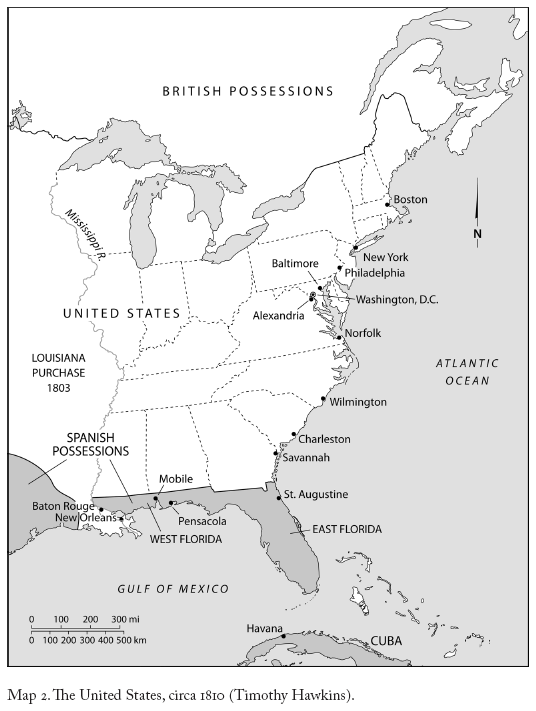

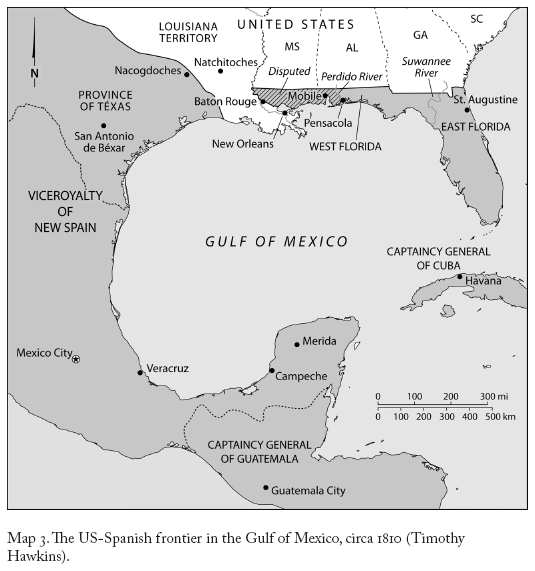

Illustrations

MAPS

FIGURES

Preface

As is the case with many second books, this project had a long gestation. The original idea for this book arose in the mid-1990s when I was deep into the research that eventually resulted in an earlier work, Jos de Bustamante and Central American Independence. As I explored the Guatemala City archives for information on the Spanish kingdoms response to the imperial crisis of 1808, I took note of the frequent expressions of concern on the part of local officials about French subversive activity. In some cases, the colonial administrative records included names of suspected French agents. Additionally, prosecutors who brought cases before Guatemalas various judicial institutions often emphasized links (or at least sympathy) between local malcontents accused of acts of disloyalty and foreign conspirators. The possibility that a French espionage network had in fact operated in Central America intrigued me, especially since the archival evidence left little doubt that Spanish officials governed as if one existed. Consequently, while my first book would make mention of the Guatemalan cases, I became convinced that a second projectdevoted to the origins, impact, and larger context of Napoleonic subversion in the Americaswas warranted. Fifteen years of following the emisario francs (French emissary) back and forth across the Atlantic has led me to this point.

I completed most of the research for this book in Spanish archives. The Archivo Histrico Nacional (AHN) in Madrid in particular stores the bulk of the diplomatic correspondence and government records used here. Documents from the Archivo General de Centroamrica (AGCA) and the Newberry Library are central to the case study at the heart of chapter 6. The George A. Smathers Libraries of the University of Florida, notably the Department of Special and Area Studies Collections, provided access to valuable material from its East Florida Papers and the Papeles de Cuba holdings from the Archives of the Indies (AGI). Details about the southwest borderlands came from holdings in the Latin American Library atTulane University and the Bexar Archives of the University of Texas. A visit to the Archivo General de la Nacin (AGN) in Buenos Aires allowed me to explore the unique history of the Ro de la Plata in the decades following the French Revolution. Microfilms of the National Archives Notes on the Spanish Legation provided a major source of information about both the American and Spanish diplomatic posturing during this period, as did the Thomas Jefferson and James Madison Papers. All scholars of the period owe a debt of gratitude to the librarians and archivists working at the National Archives, the Library of Congress, and various state archives, who provide public access to such valuable historical material through publications and online websites.

Acknowledgments

Numerous family members, friends, and colleagues supported me as I worked to bring this decade-long project to completion. The History Department at Indiana State University (ISU) was an ideal professional home during this period. A number of grants from ISUs research funds provided critical financial reinforcements for my trips to Spain and Argentina, while a Summer Library Grant from the University of Florida enabled me to spend two weeks at the Smathers Library. Chapters 4, 5, and 6 in particular benefited from the critiques of panelists and participants at the scholarly conferences where they were first exposed to public scrutiny. In this respect, I wish to recognize the thoughtful comments and valuable advice I have received over the years from Richmond Brown, Alvis Dunn, Laura Matthew, Blake Pattridge, Jordana Dym, Christophe Belaubre, and John Savage. Special thanks to Lyman Johnson and Mark Burkholder for helping me to work through my evidence and refine my argumentespecially that one time over lunch at the Acme Oyster Bar in New Orleans. I am grateful to Bill Nelson for the care he took in preparing the maps used here. I would like to express my appreciation to Wendi Schnaufer and the staff of the University of Alabama Press for their editorial assistance and unwavering support. Finally, I would like to recognize Alabamas anonymous readers for the time they spent reading, reviewing, and evaluating this manuscript. Their guidance and suggestions were invaluable.

Despite so much support and my best efforts to craft the perfect book, I am ultimately responsible for any errors of fact or interpretation found herein.

INTRODUCTION

Chasing Shadows

French Subversion in Spanish America

We must inform all priests and their assistants that reports have arrived which confirm that the French have entered Andalusia and that the Intruder King has sent emissaries, including four destined for this kingdom, to deceive, seduce, and win over to his authority the inhabitants of the Americas.

Isidro Sicilia, archdeacon of the Guatemalan Metropolitan Church, May 23, 1810

Between 1808 and 1812 Spanish officials loyal to the deposed King Fernando VII inundated Spanish America with warnings about Napoleonic emissaries, spies, agents, and other foreign provocateurs. While local governments ruled over subjects who offered frequent and passionate displays of loyalty to the Bourbon monarchy, colonial authorities nevertheless found their administrative policies and defensive measures shaped by a profound anxiety over French-inspired insurrection. Officials responded to this perceived threat by publicizing regular bulletins about suspected cases of espionage, offering rewards for information leading to the capture of spies, threatening severe punishment to afrancesados (Francophiles), and exhorting the public, often via the clerical establishment, to be on guard against revolutionaries. They instituted severe restrictions on travel, prohibitions on the use of Spanish American ports by French ships, and increased scrutiny of the transit documentation required of all foreign vessels. The governments of individual colonies called for the creation of new militia forces, sought fundseither through forced loans or