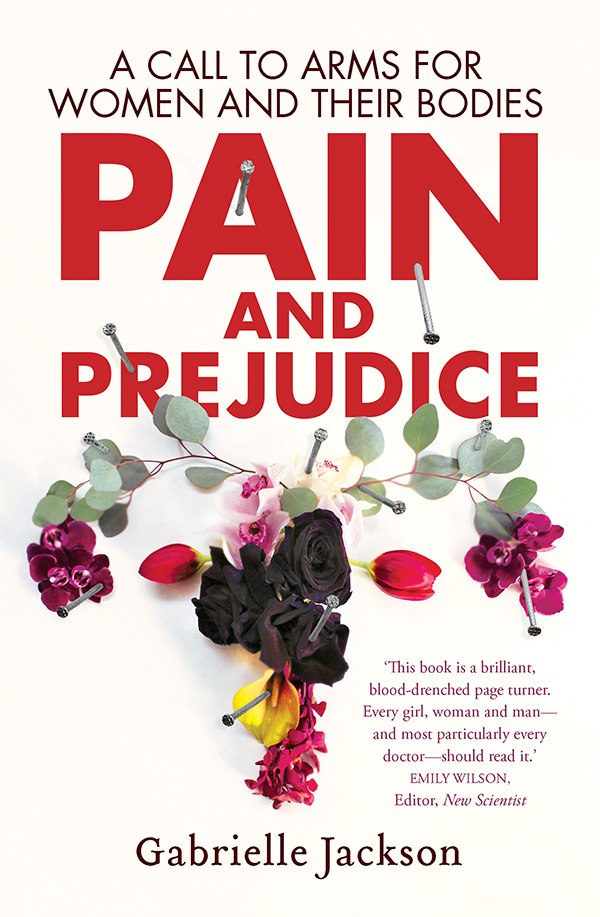

PAIN

AND

PREJUDICE

A major contribution to feminist writing of the 21st century. Jackson takes her own story of endometriosis, a neglected and mistreated condition, and builds around it a careful analysis of how womens pain has been ignored or belittled over centuries by a sexist medical profession. She then turns to recent developments, reporting on evidence-based research that is starting to bring better options to women experiencing chronic pain. Well written, and sometimes hilarious, with excellent chapters on womens anatomy and physiology, this is highly recommended reading for all women, their partners and familiesand their doctors.

CAROLINE DE COSTA, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, James Cook University

Gabrielle Jackson deploys facts to tear away the destructive myths that surround womens health and to unpick the sexism woven so tightly into the medical system. On behalf all the women who continue to suffer unnecessarily, she demands change.

LENORE TAYLOR, Editor, Guardian Australia

This book is a brilliant, blood-drenched page turner. Every girl, woman and manand most particularly every doctorshould read it. Gabrielle Jackson has made it her personal mission to end the rampant ignorance around women and the pain they suffer every day as a normal part of being alive.

EMILY WILSON, Editor, New Scientist

Gabrielle Jackson is an associate news editor at Guardian Australia, and was previously opinion editor there. Before that, she was a senior journalist at The Hoopla. Gabrielle has lived and worked in the USA, UK and Australia as a journalist and copywriter. She currently lives in Sydney and commutes regularly to the Riverina district of New South Wales. Gabrielle was first diagnosed with endometriosis in 2001. In 2015 she was also diagnosed with adenomyosis. After writing about endometriosis for The Guardian in 2015, she became interested in how womens pain is treated in modern healthcare systems and has been researching and writing about the topic since then.

Gabrielle loves cooking and is a kebab connoisseur. In 20112012, she spent eight months travelling from Europe through the Middle East to Asia researching the history of kebabs and their journey to the western world. She returned to Australia after being run over by a train in India.

Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

First published in 2019

Copyright Gabrielle Jackson 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Extracts from Andrew Scull, Hysteria: The disturbing history, Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009 are reproduced with permission of the licensor through PLSclear. Extracts from Sander L. Gilman, Helen King, Roy Porter, G.S. Rousseau and Elaine Showalter, Hysteria Beyond Freud, University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA, 1993, reproduced by permission of University of California Press and Copyright Clearance Center.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76052 909 3

eISBN 978 1 76087 213 7

Illustrations on pages by Ngaio Parr

Index by Garry Cousins

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover photograph: Sandy Cull (flowers); Shutterstock

CONTENTS

I was watching my young nieces swimming lesson when the familiar pain hit. It began with the usual ache in the gut that travelled down my legs and up my back but became sharp so quickly I doubled over. I felt beads of sweat accumulate at my temples and under my arms. A weakness overcame me and I knew I had to get to the toilet fast. After telling my sister I didnt feel well, I hobbled off to the public bathroom. I didnt have any painkillers on me and the nausea just got worse. I sat on the toilet bent in half at the waist. I had diarrhoea but it didnt make me feel better. I was sweating a lot.

My nieces lesson finished. She and my sister showered, changed, ate a snack and were ready to go. My sister was calling for me. I hobbled out of the cubicle, trying not to worry anyone. I vomited in the carpark and held back tears. The pain was so severe, I could barely talk to answer my sisters questions.

At her place she gave me some painkillers and prepared a hot water bottle for me as I vomited again in the toilet. She rang our mum for advice and kept asking me, What can I do? But there was nothing she could do. Being at her house was at least better than having to lie down in a public bathroom alone.

Now I never leave home without a bag filled with painkillers, anti-inflammatories, and drugs to prevent abdominal cramping, nausea and diarrhoea. Ive grown used to the sudden onset of overwhelming pain and nausea, and the embarrassment that causes. Ive become expert at pinpointing the exact moment I need to get homewhen the beads of sweat begin to form at my temples, under my arms and at the base of my spine. Around the same time, a weakness in my legs gives way to stabbing pains in my lower abdomen. When that happens, I know I have half an hour to take some painkillers and anti-nausea drugs, fill a hot water bottle and be still.

If I cant get home in time, things can get ugly.

_________________

I have a disease that I know nothing about.

I thought I knew everything, or at least a lot about itbut that turned out to be very far from the truth and also very bad for my health.

That was the first sentence of a feature I wrote for The Guardian about having endometriosis. I was 38 and had suffered with various health problems since my teens. Id always thought of myself as weak; I was jealous of the energy my friends could muster. I knew I had a disease but didnt want to be seen as sickI didnt want to be a whinger or thought of as no fun. At some point I normalised most of my pain, and I believed my constant back and hip aches were the result of a skiing accident Id had at nineteen.

But if I was cursed with endometriosis, I was blessed with a cheery disposition and an almost pathological optimism. This enabled the central paradox of my life. I was never one to suffer in silence; people close to me knew of my ongoing physical ailments while having little comprehension of their emotional toll. Like me, my loved ones didnt ascribe all my loud complaints to the burden of a chronic disease. I gave myself the title of hypochondriac before it could become a complaint whispered behind my back.

I lived in cycles. For months at a time Id be incredibly busy with work and social commitments, then Id become exhausted: in intense physical pain, emotional and always on the verge of tears. During these periods, I locked myself away at home, took long baths and lots of painkillers, and fortified my body and mind for the next cycle. My only excuse was, Im just so tired.