Contents

Guide

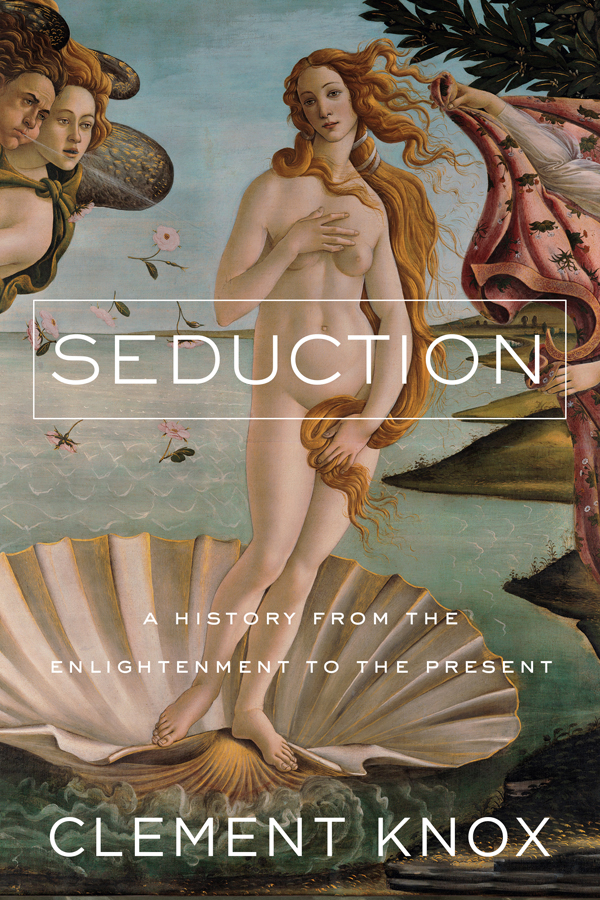

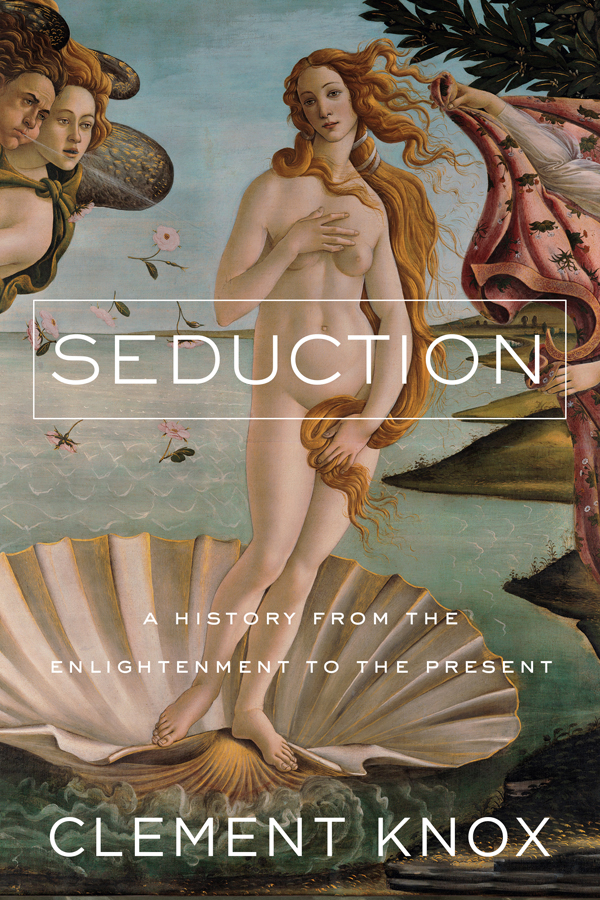

SEDUCTION

A HISTORY

FROM THE ENLIGHTENMENT

TO THE PRESENT

CLEMENT KNOX

SEDUCTION

Pegasus Books, Ltd.

West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2020 by Clement Knox

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition February 2020

Interior design by Sabrina Plomitallo-Gonzlez, Pegasus Books

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN: 978-1-64313-199-3

ISBN: 978-1-64313-384-3 (Ebook)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company

To My Parents

When we behold two males fighting for the possession of the female, or several male birds displaying their gorgeous plumage, and performing strange antics before an assembled body of females, we cannot doubt that, though led by instinct, they know what they are about, and consciously exert their mental and bodily powers.

Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man , Chapter VIII

I n 1873, a Georgia court heard the appeal of Myron Wood against his earlier conviction in a seduction case involving Emma Chivers. Wood was a reverend, schoolmaster, and Civil War veteran, a pillar of the community in Decatur, the seat of DeKalb County, in northeast Georgia. Chivers was fifteen when she first met Wood, who was her teacher at school and her pastor at church. She was the daughter of a destitute widow, so poor that Wood took the family into his own home to help relieve their poverty. But Wood had other motives. His own wife was terminally ill, and he seduced Chivers, promising her that he would marry her once his sick spouse died. Chivers trusted him, respected him, and probably somewhat feared him, and she submitted to his advances, the first time she had ever done so. A child was born, whereupon Wood went back on his word and denied all responsibility. This was the background to Chiverss initial, successful lawsuit. On appeal Wood adopted a new strategy. He did not deny that the affair took place, simply that Chivers was ineligible for protection under the seduction statute as she was a lascivious girl, sluttish, and primed for sin. Woods lawyers marshaled an array of witnesses willing to testify to Chiverss low morals and lustful nature. The sins of the mother were visited upon the daughter. A spinster was found who claimed that Chiverss mother was rumored to have consorted with black men and may have even run a brothel in Atlanta. Classmates took to the stand. They revealed that Chivers was not in the habit of concealing her legs as a good Christian girl was expected to do. Some had seen her hug and kiss young men. Others noted her penchant for unfruitful fruit-picking expeditions with local boys. Was it not true, the counsel for the defense asked her, that she was known to go blackberry hunting with young men and [bring] no blackberries back?

The state supreme court sided with Wood. Emma Chivers, the justices ruled, was not a seducible woman.

Seduction is normally conceived of as something that happens between individuals. The case of Myron Wood and Emma Chivers is one example among countless available that this is not the case. A casual survey of modern Western history reveals that as long as sex has been considered a private matter, seduction has been considered a public concern. For centuries, seduction had a legal dimension and today remains a perennial problem for human resource professionals in corporations and administrators at universities. For just as long, writers, dramatists, and filmmakers have relied upon the tales of seduction to titillate and provoke their audiences. The rise of seduction as a popular literary genre was simultaneous with the birth of modernity. Widely considered the first novel in English, Pamela (1740), is about the trials faced by a precariously employed young woman working for a wealthy and sexually rapacious young man. An absurd conceit for a book, one might say, though the immense popularity of this tale in its day is better understood when one considers its elements as being essentially indistinguishable from one of the great bestsellers of our own time, Fifty Shades of Grey (2011). Fictional seduction narratives entertain us in equal measure as they disturb us. Seduction draws into its dragnets a whole range of sensitive issues. To think about seduction as a social concern is to engage with matters of morality, philosophy, politics, class, race, and gender. If these subjects fascinate in fiction, then they scandalize in fact. Factual instances of seductionbroadly definedhave dominated the attention of headlines, courtrooms, and legislative bodies from the eighteenth century to the twenty-first. All this to say, seduction very clearly has a social and cultural existence that can be charted, yet its history has never been written. There seems to be no clear reason why that should continue to be the case.

Every aspect of human experience has its history; the problem is identifying how best to measure it. The unit of measurement for the history of seduction is that strange and powerful thing, the seduction narrative. The basic claim of this book is that the seduction narrative is a product of the modern world and serves as a vehicle for the exploration of modern values, modern experiences, and modern concerns.

This is not to say that seduction never existed in fact or fiction before the onset of modernity. The moons of Jupiter are named for four of Zeuss most celebrated seductions. The nymph Io he enshrouded in darkness and then turned into a snow-white heifer to conceal her from his jealous wife. Callisto, the Arcadian virgin [who] suddenly caught his fancy and fired his heart with a deep-felt passion, he approached in the guise of her mistress, the goddess Diana, before taking her in his arms and revealing his identity. To win the Phoenician princess Europa, he discarded his mighty sceptre and clothed himself in the form of a bull. Once he had lured her to sit on his back, he swam out to sea, taking her all the way to Crete, where they eventually had three children together. To secure the Trojan youth Ganymede, Zeus took the form of an enormous eagle and swooped down from the skies and carried him away to Mount Olympus. All these stories are recorded in the Metamorphoses , written by the Roman poet Ovid, who is arguably more famous for authoring the first-ever seduction manual, the Ars Amatoria , in the second century BC. Ovids frank treatment of seduction scandalized the emperor Augustus, and Ovid was sent into exile on the Black Sea. Whatever tribulations he experienced in his own lifetime, Ovids legacy endured. In the premodern world he was the paradigmatic writer on seduction, name-checked by Chaucer and Shakespeare and avidly read by every educated young man. Indeed, Ovids influence was so great that it became an inspiration for perhaps the first proto-feminist analysis of seduction. Writing in the early fifteenth century, Christine de Pizan mocked the clerks who lived by Ovids sexual commandments while lamenting that the sexual culture his writings had helped forged made life impossible for women. For a beautiful woman to keep herself chaste, de Pizan wrote, is like being in the midst of flames without getting burnt on account of her having to fend off the attentions of young men and courtiers who are eager to have affairs.