Contents

Guide

Page List

How to Teach Philosophy to Your Dog

Exploring the Big Questions in Life

Anthony McGowan

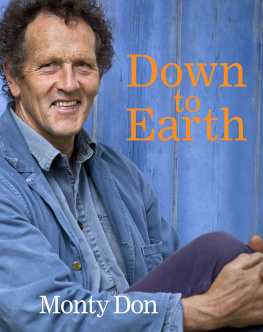

To Monty, of course, who has brought so much love into our family.

Contents

Therefore the brutes are incapable alike of purpose and dissimulation; they reserve nothing. In this respect the dog stands to the man in the same relation as a glass goblet to a metal one, and this helps greatly to endear the dog so much to us, for it affords us great pleasure to see all those inclinations and emotions which we so often conceal displayed simply and openly in him.

Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Idea, Volume II, Chapter V, translated by R.B. Haldane and J. Kemp

Outside of a dog, a book is a mans best friend. Inside of a dog, its too dark to read.

Attributed to Groucho Marx

How to Teach Philosophy to Your Dog is intended as a welcoming introduction to the world of philosophy. As with walking the dog, there are always different routes you can take in this sort of enterprise, varying in the direction, the distance, and even the purpose. Is it exercise, entertainment, or merely a quickie to get your business over and done with as efficiently as possible? Some introductions to philosophy simply start at the beginning, with the speculations of the earliest Greek thinkers in the sixth century bce, and gradually work their way through the ages, until we reach whatever the now is for that author. Others are more biographical, sugaring the pill with anecdotes about the eccentricities and oddities of the philosophers. More recently, it has become popular to take a purely thematic approach, breaking the subject down into questions or themes, with an emphasis on topics that are still hot.

These different approaches reflect the fact that philosophy has an oddly hybrid nature its less of a purebred Afghan, and more of a labradoodle. English literature is a subject that essentially consists of its history. Chaucer and Shakespeare and Austen and George Eliot are not read for their historical interest, but because their writings are still living works of art. Furthermore, their greatness lies not in some ideas that could be abstracted and summarized, but in the language: the words and sentences and paragraphs and longer, deeper, musical movements of the texts.

Mathematics and physics, on the other hand, are subjects that can be taught without ever mentioning the backstory. To calculate the area of a circle, you dont need to know that pi was first roughly computed by the Ancient Egyptians and Babylonians, and then brought to seven decimal places by Chinese mathematicians in the first millennium ce: you just need a pocket calculator. And Newtons laws of motion have a meaning and importance that have nothing to do with the words in which he expressed them. Aristotelian physics, with its abhorrence of the void, its straightforwardly wrong conception of motion and its ingrained cosmology, with the Earth at the centre of a static universe frozen into a series of concentric crystalline spheres, is of no use whatsoever to a modern scientist, other than to make her feel superior.

Philosophy spans both these worlds. Its certainly possible to discuss the ideas of Plato, Aristotle and Wittgenstein without ever quoting them. In this sense, they are like Newton. However, the problems of philosophy tend not to get solved. They are news that stays news. Professional philosophers today still engage with Aristotle and Descartes, still argue with Locke and Bentham, in a way that no scientist would think to dispute with Archimedes or Copernicus. And so the history of philosophy never goes away, never becomes irrelevant.

Its also a fascinating story in its own right. And so, in this book I have tried to capture that crossbred labradoodleness of philosophy. The form I have adopted tips a hat to the history of the subject. It is structured as a series of walks, which connects to Aristotles practice of teaching while on the move a habit that gave the name Peripatetic, from the Greek word meaning to walk about, to his school. And on these strolls my dog Monty and I, in the dialectical tradition of Socrates, discuss the central problems in philosophy, taking the broad subject divisions of the field as our guide.

After the introduction, the first three walks are about ethics and moral philosophy. We then have a couple of minor side-strolls, one dealing with the concept of free will, and another on logic. Next, there are three walks in which we discuss metaphysics, those knotty questions around the nature of reality and existence. After that we stroll our way through three walks on epistemology, or the theory of knowledge. Four walks, really, as theres also a discussion of the philosophy of science. Finally, theres a chapter on the meaning of life, which also briefly examines some of the proofs for the existence of God.

Although this broad structure is thematic, within each subject we look at what the great philosophers have had to say about it. My hope is that this will both help the reader to understand the problem, and also to give a real sense of the history and development of thought.

I should say that this is a very partial history of ideas, in that I have concentrated on the Western philosophical tradition. This is not because of a parochial disdain for Islamic or Chinese or Indian philosophy, but simply because these are vast and complex fields in which I have no expertise, and it would have been insulting to add snippets, merely to make this work seem more diverse. Each of the great non-Western traditions deserves a Monty of its own

Finally, this is not one of those introductions to philosophy that gives the reader bullet points to help revision. It is arranged as a series of walks, and just as on a walk, there are times when we wander off the path, beat around for a while in the undergrowth, disturb a rabbit, feed the ducks. There is the occasional dead end. And sometimes, you have to walk beside a busy road, or through a field of stubble, before you get to the good bits, that lovely clearing in the woods, or the stream with the kingfisher.

I have a dog, a scruffy Maltese terrier, called Monty. I say have not to suggest ownership, particularly, but more in the way youd say I have dandruff or a cold. Monty looks like a failed cloud that has fallen to earth and rolled around in the muck for a while. He has inscrutable black eyes, a black nose and a nicotine-stained moustache gained from sticking his snout into aromatically enticing nooks and crannies, both biological and geological.

When it comes to intelligence, Maltese terriers are generally described as middling: slower-witted by far than highly strung poodles and chess-playing collies, but a notch or two up from the bewildered boxer, staring in bafflement at a tennis ball in the hope it comes back to life, or stoner Afghans, intellectually exhausted by the effort of not swallowing their own tongues. Monty has no tricks, and he doesnt come, or even sit reliably; although he will wait passively for you to approach him if the world has nothing more interesting to offer. His greatest triumph came when he won Best Boy Dog at the Cricklewood, or, rather, Cricklewoof, dog show. A rabbit was runner-up. Third prize went to a teddy bear.

Although Ive been a little harsh on his intellectual accomplishments, Monty has a sort of earnest, quizzical look to him, as if hes methodically striving to understand some secret code, or seriously pondering the hidden meaning of the universe. I think of him as a sort of Dogter Watson no, dont worry, this isnt going to be one of those books full of awful puns, there will be no more. If hes Watson, does this make me Sherlock? Alas, I fear that Monty and I are like one of those double acts made up of two straight men we are both Watsons, both of us huffing and puffing our way to a truth that more agile minds might reach with greater speed, if not accuracy.