Contents

Guide

Page List

Acer rubrum Halka.

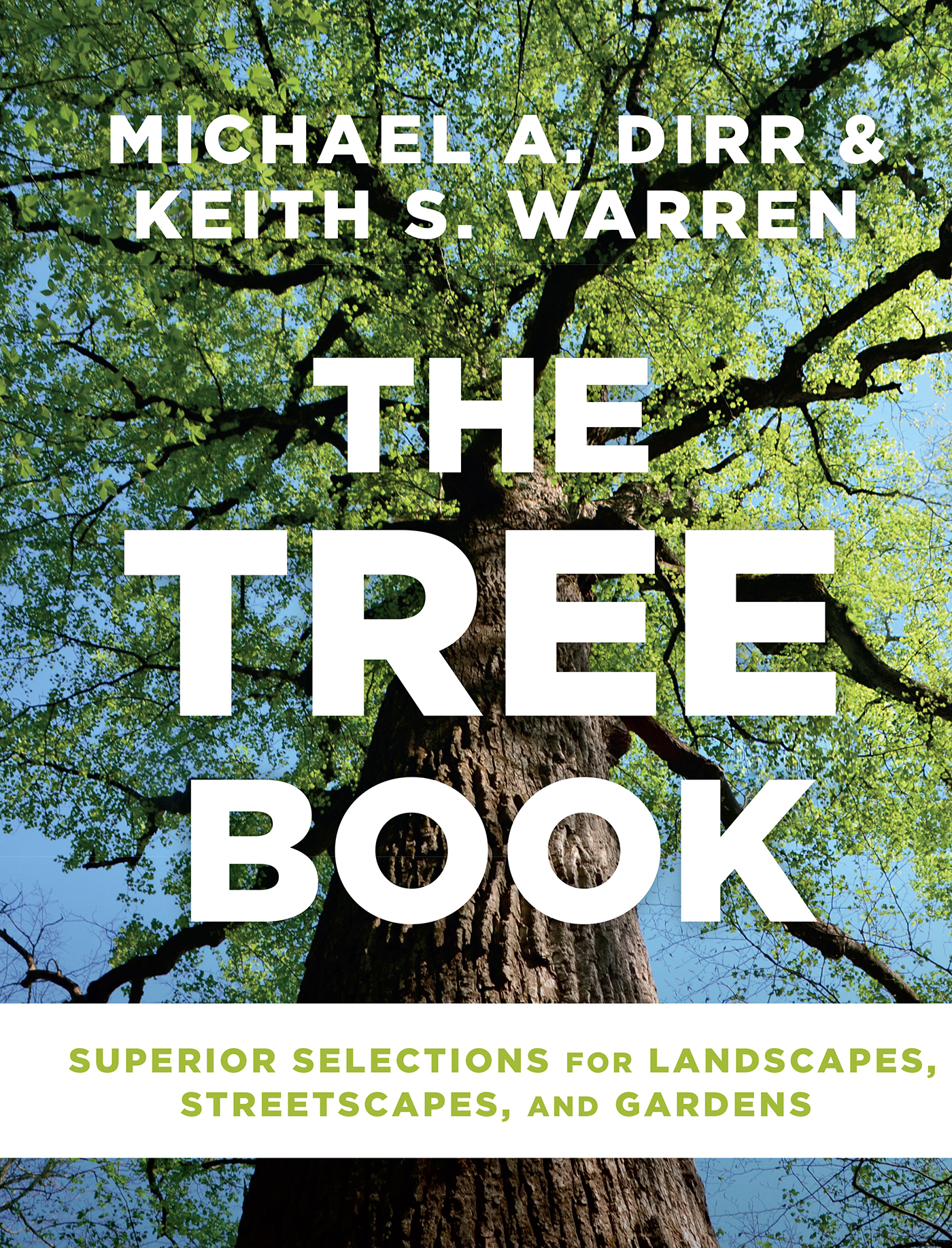

The

TREE

BOOK

Superior

Selections for

Landscapes,

Streetscapes,

and Gardens

MICHAEL A. DIRR

& KEITH S. WARREN

TIMBER PRESS

PORTLAND, OREGON

To our families,

with love, and to

those who plant trees,

with great appreciation

Contents

Introduction

We love trees. For both of us, this love affair began early in lifewith the deciduous monarchs of the Midwest (for Dirr) and the great coniferous rainforests of the Pacific Northwest (for Warren). We both spent our college years immersed in plants and began horticultural careers immediately thereafter, which we have each pursued for well over 40 years. One followed the path of an educator, as a university horticultural professor and researcher, and later, a plant breeder. For the other, the career path was in tree production as a nursery manager and researcher, and later, a tree breeder. Our paths began crossing some 30 years agouniversity horticulture research meets commercial nursery productionand the flow of both ideas and plant materials has increased steadily ever since. Our horticultural thoughts often cross-pollinated each other, and soon the idea of co-authoring this book germinated. We both view trees as noble works of nature, we are humbled by their greatness, and we hope our works and words, in this book, will enhance and increase their presence in our society.

Whether walking through the redwoods of California, admiring the massive structure of a Midwest oak, or perhaps (having exited a hot freeway) pulling into the cool deciduous shade of a tree-lined street in an eastern city, we never cease to be amazed by the majesty of trees. The authors feel this every day and wonder if it is not so for everyone. Doubtless our bond with trees is unusually strong, as the two of us feel kindred spirit with trees, but it would be hard for us to understand someone who did not share a little of this feeling. At least to us, it seems to be a part of our humanity.

The advance of civilization has been largely about turning the wild environment into what is now called the built environment, and we have to admit the conquest of nature has given us great creature comforts. But this comes at a price. At first, only a few voices, Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, and others, questioned the rapid conversion of wild to urban; today, organized environmental groups number in the hundreds, if not thousands, and are among the fastest-growing nonprofits. The worlds first national park, Yellowstone, was created in 1872; today, the United States has 59 national parks, and the concept has spread to countries around the world. Some 15% of our planet (much of it ocean) enjoys some form of conservation protection. It is clear that as people have urbanized their world, they still need and cherish nature.

Humans have certainly conquered the globe, living in every environment from the Antarctic ice to driest deserts. But conquest is almost always destructive, and populations prosper best in climates where trees are present. As civilization developed, trees were cut as a resource or cleared for agriculture. But soon after we did this, we realized we need trees, and we replant, selectively, to fill our needs. The woodsman cuts timber to make the lumber, then replants so the cycle can be repeated. The farmer clears for his crops, but then plants trees to break the wind and shade his house from the sun. As our urban centers have developed and grown, native trees are lost to houses, businesses, and endless miles of concrete. Then in our naked cities we feel the need for something natural, we miss the beauty, and so we plant our city streets, parks, and gardens with trees. People are attracted to a woodland environment, partly open with sunny meadows and partly closed with trees. We so often replicate this in our landscapes and city parks, partly open with grass and shrubs and partly closed in with trees for shade and screening. This seems to be where we want to live. We clear lots to build houses; then we plant trees for our homes.

Forests reconnect us with nature.

Research at Yale University estimated that the Earth holds 6 trillion living trees. But the same 2015 study also determined that the Earth has suffered a 46% loss in its tree population since the dawn of human civilization, and that humans are the main driver of that loss. The world is currently losing about 15 billion trees per year. Tropical and boreal regions hold the largest portion of the remaining tree population, with the temperate zone holding only 22%. Clearly, widespread reforestation would be good for the planet. But what we do in our cities is disproportionately important. Planting trees in human population zones, especially in cities, has a multiplier effect on its benefits, as urban and residential trees mitigate so many human-caused adverse effects on the environment.

Trees shade the city and soften the harsh rectangles of our buildings.

Beyond the aesthetic, trees bring us practical benefits. Environmental analysis confirms this, showing that deciduous trees on the south and especially the west side of a house can moderate the microclimate and greatly reduce energy consumption. As properly sited trees grow over time, their energy savings grow as well, making them incredibly cost-effective additions to the property. Mature trees add significantly to neighborhood home values, and research on the effect of tree loss due to the emerald ash borer has shown that crime rates and both respiratory and cardiovascular death rates have gone up with loss of the urban canopy.

Urban parks relieve stress, creating spaces for people to relax and enjoy their humanity.

A study led by Theodore Endreny, State University of New York, published in 2017, determined the value of trees to the worlds largest cities, megacities with populations over 10 million. Urban trees added a mean value of $505 million (2017 dollars) to each city, or $1.2 million per square kilometer of tree cover. Economic value was gained by air pollution reduction, stormwater abatement, reduction of energy costs, and carbon emission reduction. Significantly, by far the greatest value was found to be from the health benefits derived from air pollution reduction. Trees significantly reduce dangerous air particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers; these microscopic PM2.5 particles have an adverse effect on human health, notably to the respiratory and cardiovascular systems, and result in high health care costs and premature death. For health reasons, people need trees.