Contents

Guide

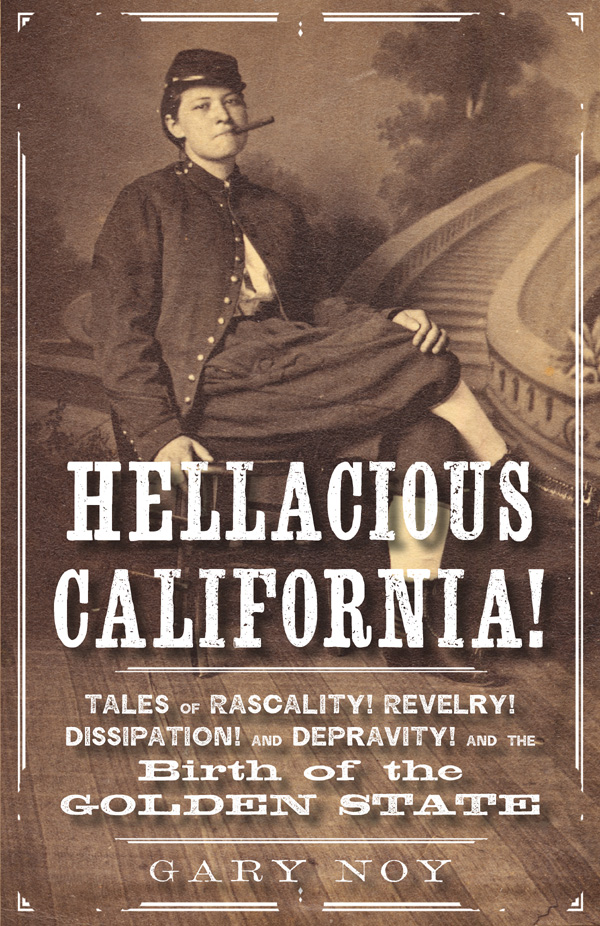

Copyright 2020 by Gary Noy

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

Cover Art: Portrait of Soldier, photograph by Jacob Shew, c. 1865.

Image courtesy of the California State Library, Sacramento;

California History Section, Digital ID: 2008-0327.

Cover Design: Ashley Ingram

Interior Design/Typesetting: Rebecca LeGates

Published by Heyday in collaboration with Sierra College Press

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, California 94709

(510) 549-3564

heydaybooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my Grandma, Mary Ethel Lewis Winkle, who sparked my fascination with nineteenth-century American history

It is my unbiased opinion that California can and does furnish the best bad things that are obtainable in America.

Hinton Rowan Helper,

The Land of Gold: Reality versus Fiction, 1855

CONTENTS

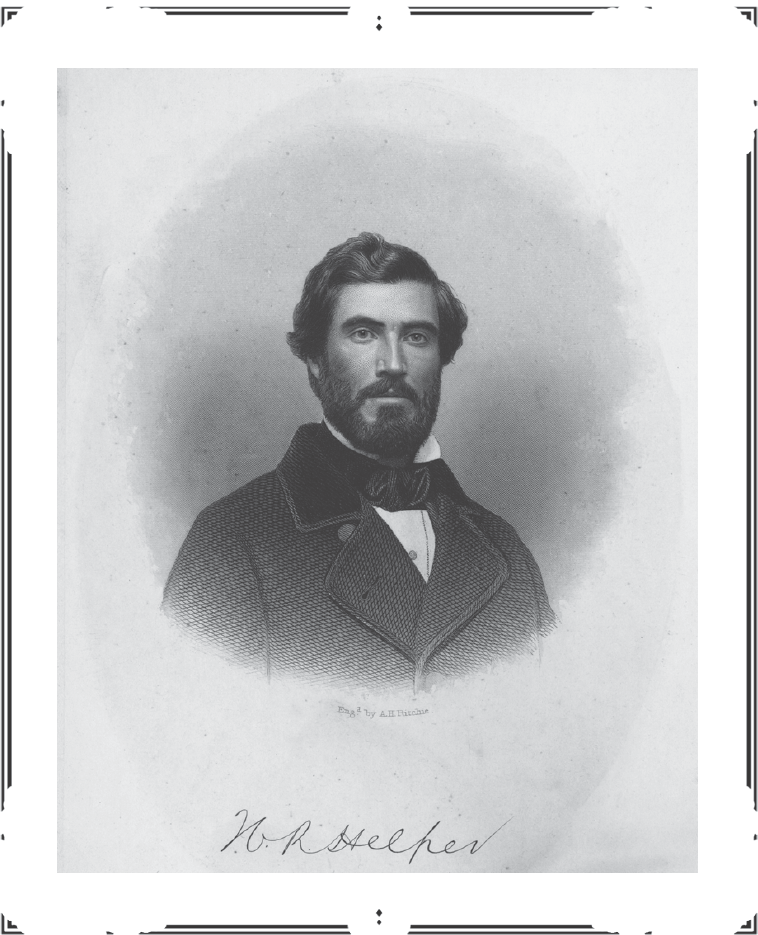

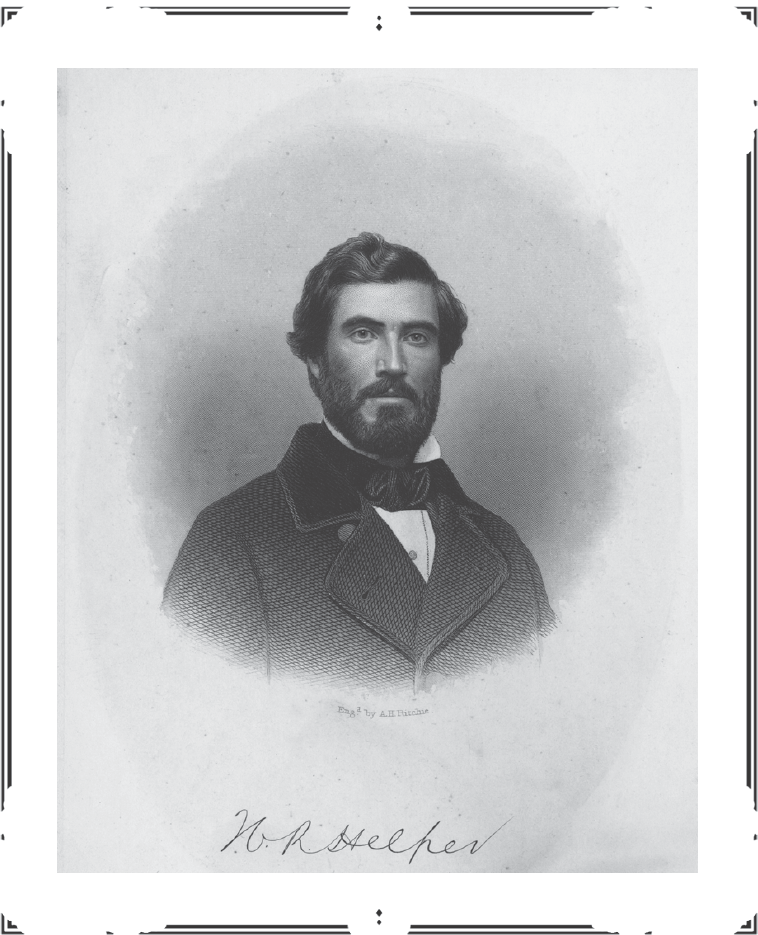

Hinton Rowan Helper, c. 1860. From Helper, The Impending Crisis of the South (New York: A.D. Burdick, 1860), frontispiece. Image from a volume in the authors personal collection.

INTRODUCTION

I n May 1851, San Francisco was a city in recovery. On May 3 and 4, a massive conflagration had swept through the bustling city, and for ten hours the fire raged, swallowing everything in its path. When finally quenched, the flames had destroyed two thousand buildings, representing about three-quarters of the city, and at least nine lives were lost. It was as if the God of Destruction had seated himself in our midst, and was gorging himself and all his ministers of devastation upon the ruin of our doomed city and its people, reported San Franciscos Daily Alta California. Most of the city was uninsured, and conservative estimates placed the damages at roughly $12 million (about $400 million today).

But San Franciscans were resilient. French argonaut Ernest de Massey, who had repeatedly witnessed both the destructive power of fire in Gold Rush San Francisco and the buoyant resurgence of the city, admiringly commented in a letter to his cousin in France: One calamity more or less seems to make no difference to these Californians. Rebuilding began immediately, and a chorus of hammers and saws filled the air for weeks. In the hyper-accelerated Gold Rush society, however, construction was often rapid, slapdash, and dodgy. On Sunday, May 25, 1851, the Alta California noted that a new building, recently erected on Central Wharf, was blown down by the force of the wind yesterday.

The weather that day was a great source of amusement in the paper:

There was great sport yesterday not withstanding it was Sunday, the streets being converted into race courses, and races being run between men and their hats. The weather was highly favorable, being gloriously windy, and tiles [hats] of all descriptions blew off the heads of their owners and filling with the breeze galloped off, making much better time than those in pursuit.

But the fierce gale and precarious edifices meant little to a hardy band of travelers on the sleek clipper ship Stag Hound, which dropped anchor in the harbor that breezy Sunday. This moment marked the beginning of their grand Gold Rush adventure and what they devoutly wished would be the dawn of a new life. They were intensely optimistic, expectant and energized, and inspired by the seemingly irresistible compulsion known as gold fever. The seven paying passengers aboard the Stag Hound had arrived that morning after an eventful journey of 113 days from New York to San Francisco via Cape Horn, a voyage that included both high adventure (they had deftly rescued a shipwreck survivor off the coast of Brazil) and deep discomfort (most of the passengers had endured weeks-long bouts of seasickness, due in part to a terrifying storm near Bermuda and seven days and nights of ferocious weather rounding the cape).

Among their number was a confident twenty-one-year-old from North Carolinasinewy, bearded, and possessed of a resolute gaze and a steely demeanor. His name was Hinton Rowan Helper and he was excited to begin his quest for golden glory, charged with the determination that animated the many hundreds of thousands of people who experienced the California Gold Rush. Helper presumed success and trusted that his stay in California would be brief, pleasant, and lucrative.

It was not. Hinton Rowan Helper hated California.

The young explorer spent three long, frustrating, tiring years in California. As did most, he failed miserably as a miner. Helper unhappily recalled that during one season, he realized a net profit of ninety-three and a quarter cents in three months... or a fraction over a cent a day. He hungered to escape from this private hell and longed to return to his romanticized vision of North Carolina, a world of gentility, grace, and agrarian virtues.

Broke and disillusioned, Hinton Rowan Helper returned home in 1854 and vowed to persuade others to shun California and avoid the appalling Gold Rush torment he had endured. To that end, he put his nose to the grindstone, weaponized the alphabet, and swiftly produced a vitriolic diatribe entitled The Land of Gold: Reality versus Fiction, published in 1855. Helpers venomous broadside had elements of truth, but the best-selling book was also hyperbolic, full of overstated statistics and dubious anecdotes, not to mention laden with the blatant bigotry and casual racism characteristic of the era. It is best remembered for his caustic commentary on nineteenth-century California culture.

While Hinton Rowan Helper found most of California reprehensible, he did tender this backhanded compliment:

I will say, that I have seen purer liquors, better segars [cigars], finer tobacco, truer guns and pistols, larger dirks and bowie knives, and prettier courtezans here, than in any other place I have ever visited; and it is my unbiased opinion that California can and does furnish the best bad things that are obtainable in America.

It is this Helper observation that provided the initial stimulus for the book you now hold: Hellacious California!: Tales of Rascality, Revelry, Dissipation, and Depravity, and the Birth of the Golden State. This book is designed to investigate the range of problematic pursuits that contributed to the California we recognize todaysome frightening, some amusing, some mystifying, all impactful. Old California was, in a word, hellacious, but even in that single word we find more than one meaning. It can, both separately or simultaneously, connote something (or someone) that is, on the one hand, astonishing or, on the other, appalling. In embodying that duality, it is a word that perfectly reflects the impressive and astounding yet disconcerting, disappointing, and, perhaps above all, complicated nature of nineteenth-century California.