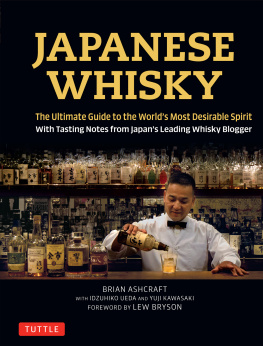

Single Malt

To Dad

New York London

2018 by Clay Risen and Scott & Nix, Inc.

Cover by Charles & Thorn.

Photography by Nathan Sayers.

First published in the United States by Quercus in 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to .

eISBN 978-1-68144-106-1

Produced by

Scott & Nix, Inc.

150 West 28th Street, Suite 1900

New York, NY 10001

www.scottandnix.com

Distributed in the United States and Canada by

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

www.quercus.com

Contents

It is never a mistake to begin a book on spirits with a quotation from Kingsley Amis, the novelist and renowned boozehound, but it seems mandatory when the books subject is whisky. For a man noted for his retrograde attitudes about women, class, and English politics, Amis was ahead of the curve in his love for single malt scotch. In the early 1980s, almost no one drank single malts; about 98 percent of all malt whisky produced in Scotland was mixed with lighter grain whisky to produce blended scotch. The world was in love with blends, but not Amis. Only the finest French brandy, a Cognac or an Armagnac, could surpass single malt scotch, he wrote in his 1983 book Everyday Drinking. As far as I know, no formal comparison or competition has ever been undertaken, but from my experience, the malt is the winner.

Things certainly have changed in the decades since. Today the scotch business is booming, and while blends still account for the bulk of its sales by volume, virtually all the growth is in single maltsthat is, the whiskies that are made by a single distillery, using only malted barley, yeast, and water, in a pot still. And while Scotland is the home of single malt scotchand where, by British law and international agreement, it has to be madeglobal demand is so high that 80 percent of it is exported. Single malts can be found on bar shelves from Melbourne to Moscow, and not just the bestsellers like Glenfiddich and Glenlivet, but everything from Aberfeldy to Wolfburn. There is not, as of publication of this guide, a distillery beginning with the letter Z, but give it time.

And yet the scotch we know today is a relatively recent development; until the early nineteenth century, it was simply whisky, and it was confined more or less to the northern and lower-class confines of Scotland. Heavily taxed, distillers produced most of their whisky using illegal stills. It was rarely barrel-aged, at least on purpose, and it was very often flavored with herbs and berries to soften its harsh edges. While exceptions abounded, it was only with a set of reforms in the 1820s, and the emergence of the blending industry in the mid-nineteenth century, that scotch emergedfirst as a popular drink for clubmen in Edinburgh and London, and then as a major export to the far-flung corners of the British empire. Blending, to produce a smoother and lighter drink, was a necessary step to winning over brandy and claret drinkers, and later bourbon and rye drinkers, but it often robbed the spirit of its aggressive nobility. The clubmen of London had little interest in a challenging dram.

It took a century and a half for distillers and consumers to turn to the single malts that make up most of the component parts of a blend. Though single whiskies had been available in small quantities in Scotland, it was not until 1963 that Glenfiddich launched the first single malta whisky made entirely from malted barley, in a pot still, at a single distillery, and bottled and marketed as such. By the time Amis wrote his paean to single malts, many of todays leading brandsGlen Grant, Glenlivet, Macallanhad their own expressions and were selling globally. Glenlivet got in early on the American market, and today holds the number-one single malt title. Glen Grant took over Italy, and still dominates. Cardhu was and remains the most popular single malt in Spain.

Yet for all its popularity, single malt scotch is a drink of contradictions. It is one of the worlds most popular spirits, yet it is often derided as the drink of the elite. It is the definition of sophistication, yet its roots are with the half-wild Highlanders of northern Scotland. It is made from grain, water, and yeast, yet most of its flavor and all of its color come from a fourth source a drinker never sees: the cask. It is a straightforward, if not simple, spirit, yet its marketing and cachet have obscured its forthrightness and made it appear more intimidating than it should be.

The goal of this book is both to dispel the myths around single malt scotch and to provide a useful guide to new and experienced drinkers. While I hope readers worldwide will find it helpful, it is aimed at an American audiencethe first single malt guide to do so. That means tasting notes that make sense to an American palate, and a focus on the whiskies available in the United States. While there are some expensive whiskies in this book, I have shied away from the truly exorbitantif you are considering The Macallan 25 Year Old (average price $2,000), you either know enough to appreciate it, in which case you probably dont need my advice, or you have enough money that it doesnt matter, in which case you dont need my advice either.

This book, then, is for the rest of you. Which is to say, almost everyone.

Simply put, scotch is whisky made in Scotland. By British law, in order to be called scotch, it has to be made from grain, water, and yeast and aged in an oak cask in Scotland for at least three years. Trace amounts of caramel can be added for color, but never flavor. Scotch-style whisky is the default for whisky distillation in most of the world; Japanese, Swedish, Australian, South African, and many other whiskies are all typically made according to similar basic principles (Irish, Canadian, and various American whisky styles are exceptions).

There are several subcategories of scotch. Malt whisky is made from malted barley alone; if any other grain is used, in combination with malted barley or not, it is called grain whisky. If you blend together malt whiskies from different distilleries, the result is blended malt whisky, or, in the case of grain, blended grain whisky. If you combine the twomalt whisky and grain whiskyyou have blended whisky, the category that accounts for about 90 percent by volume of all whisky made in Scotland today.

Next page