FOREWORD

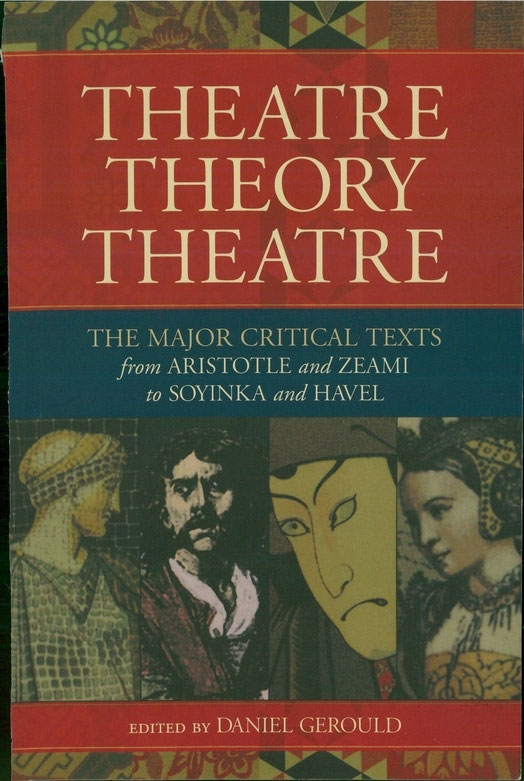

The aim of this collection is to present in a single volume of not more than 500 pages essential theorists and theories of theatre. What is innovative about the anthology is its scope and its emphasis. As we navigate the turn of the century and enter a new millennium, our perspective on the development of theatre and the theories that have shaped it is more inclusive that ever before. Natya in Sanskrit means both theatre and drama, and in the Natyasastra, one of the earliest and greatest theoretical works, both are considered together. Drama and theatre can no longer be studied in isolation one from the other, nor can Western theatre be separated from Eastern. The ideal of a world literature (first advanced by Goethe at another turn of the century) has evolved from earlier concepts of national literatures and is particularly applicable to theatrical theory.

Theatrical activity has traditionally been central to the life of the community and nation. The theory of the theatre is a reflection of politics and of international relations. It is shaped by attitudes to authority and power, the status quo and social change. The politics of theatrical theory is accordingly the focus of my introduction.

A simple set of principles has guided me in putting together this anthology. My goal has been to chart a main course through what for many readers is unknown territory and to provide a clear road map for the journey. I have chosen basic texts by the major artists, poets, playwrights, and philosophers who have shaped the ongoing theoretical debate about the nature and function of theatre. Wherever possible I have given complete essays and coherent, consecutive selections, rather than highly edited snippets. With longer works and the voluminous Natyasastra and Commentary on The Poetics of Aristotle by Castelvetro, this was not feasible. Brackets containing three periods [...] indicate that there has been an omission.

Because such a comprehensive anthology must cover many centuries, inevitable constraints of length have made it impossible to establish a beachhead on the rugged and highly contested terrain of contemporary Anglo-American academic theory. Recent theoretical approaches to theatre within the academy, addressed to a specialized readership and written in a professional jargon, belong in a seperate volume. Such a valuable collection could aptly supplement the basic texts found in Theatre / Theory / Theatre, which are designed not as a final resting place, but rather the point of departure.

Constraints of length also precluded the inclusion of footnotes elucidating the rich fabric of quotations and allusions to authors, works, ideas, and events embedded in each of the selections. Hundreds and hundreds of such notes would be required to documents adequately the incredibly diverse and dense tissue of references to be found in the forty-one texts by thirty-seven theorists. Such scholarly apparatus would make Theatre/Theory / Theatre half as a long again and change the nature of the collection. Instead of annotated versions requiring constant interruption to consult notes at the bottom of the page, the anthology presents texts to be read, savored, and pondered.

The translations are a mixture of old and new. For the sake of clarity, I have made a few corrections and minor revisions in several of the non-contemporary translations. Sometimes a version from the same period as the original captures the spirit of an older work, as is the case with the anonymous eighteenth-century rendering of Rousseaus Letter to DAlembert. Verse translations are essential for the poetry of Horace and Lope de Vega. John Coningtons mid-nineteenth century version of the Ars Poetica in heroic couplets, recalling Alexander Pope, gives Horace the right jaunty and witty tone, and Marvin Carlsons new rhymed version of The New Art of Writing Plays captures for the first time in English Lope de Vegas irony and ambivalence.

Many friends and colleagues have helped me first in the conception and then in the realization of this anthology; among them Jarka Burian, Harry Carlson, Marvin Carlson, Alma Law, Jim Leverett, Benito Ortolani, Joanne Pottlitzer, Eszter Szalczer, Michel Vinaver, Stanley Waren, and Glenn Young deserve special mention. I also wish to acknowledge the dedicated work of Marla Carlson, Lars Myers, Richard Niles, and Alissa Roost, my students in the Ph.D. Program in Theatre at the Graduate School of the City University of New York who assisted me in preparing the manuscript.

New York

August 1999

Daniel Gerould

INTRODUCTION:

THE POLITICS OF THEATRE THEORY

A Pocketful of Theory

On September 9, 1920 the twenty-two-year-old Bertolt Brecht noted in his diary, A person with only one theory is lost. He must have several, four, many! He must stuff his pockets with them as if they were newspapers, always the latest, one can live nicely among theories, one can be snugly housed among theories. If one is to get on, one needs to know that there are lots of theories.