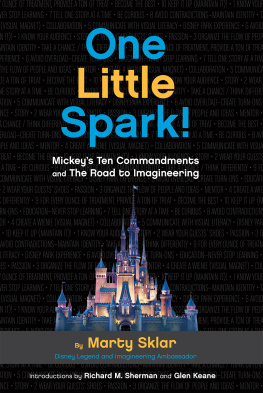

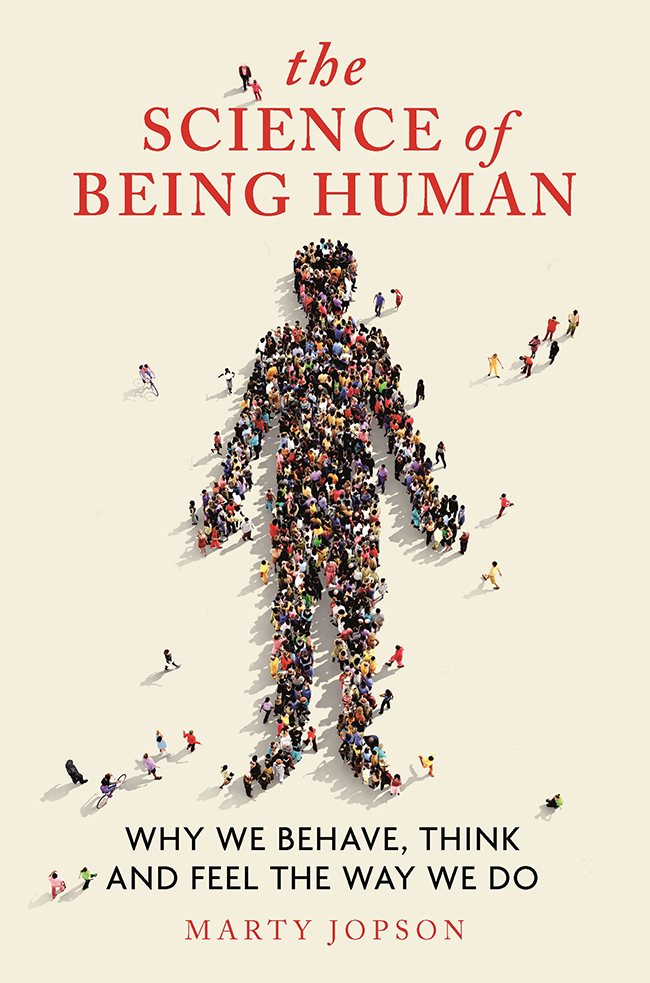

Marty Jopson - The Science of Being Human: Why We Behave, Think and Feel the Way We Do

Here you can read online Marty Jopson - The Science of Being Human: Why We Behave, Think and Feel the Way We Do full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Michael OMara, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Science of Being Human: Why We Behave, Think and Feel the Way We Do

- Author:

- Publisher:Michael OMara

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Being Human: Why We Behave, Think and Feel the Way We Do: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Science of Being Human: Why We Behave, Think and Feel the Way We Do" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Marty Jopson: author's other books

Who wrote The Science of Being Human: Why We Behave, Think and Feel the Way We Do? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Science of Being Human: Why We Behave, Think and Feel the Way We Do — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Science of Being Human: Why We Behave, Think and Feel the Way We Do" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

the

SCIENCE of

BEING HUMAN

Also by Marty Jopson:

The Science of Everyday Life

The Science of Food

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Marty Jopson 2019

Illustrations Emma McGowan 2019

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78929-164-3 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78929-168-1 in ebook format

www.mombooks.com

For my father,

who took me to museums.

CONTENTS

W e all share many things in common with each other. If you are a fan of spicy food, board games, long walks in the countryside or early twentieth-century horror fiction then you have at least something specific in common with me. One of the few things that is certain, though, is that we all share being human. What does it actually mean to be human and what is the science behind it?

To find the answer to this I have taken an eclectic approach and poked about in branches of science you may not have expected. I came across some interesting nuggets and quite a bit of maths.

I have tried to look at being human from a number of angles, starting with where we came from and, as with previous books, I have aimed to keep it up to date with the latest scientific research. This has proven challenging, as we are in a golden age of new discoveries about our deep evolutionary past and the quirks of being human. The influence of bacteria in our lives, for example, and how they might even change our behaviour, is a very hot topic for scientists.

I also wanted to explore the role and place of humans in modern societies. Clearly, our world is no longer like the one in which our ancestors evolved, but we still manage to navigate it. The digital realm features in several sections of the book, as I consider how Homo sapiens that evolved as part of a hunter-gatherer community copes with being hooked up to the internet twenty-four hours a day. The interactions between technology and our own bodies are not always, despite what the adverts tell us, as simple as they sound.

Lastly, this book takes a look at an area often overlooked by popular science focusing on being human. To paraphrase, none of us is an island and we all live out our lives surrounded by other humans. Given the way the global population is climbing, we find ourselves in groups of increasingly larger numbers. How humans interact with each other in these groups breaks all the laws of physics that we assumed would apply. New rules and new paradigms have had to be invented to explain what happens when humans get together.

Which brings me onto the one big, take-home message I have truly appreciated in writing this book. Biology is messy. Physicists, engineers and, to some extent, chemists study the world with equations and the certainty of mathematics. Biological systems and, by extension, human beings, are gloriously, unnecessarily and inexplicably complicated and counter-intuitive. This is the reason I find some scientific topics more compelling than others, and to my mind there is nothing more fascinating than the science of being human.

JUST WHO DO YOU

THINK YOU ARE?

I am a member of the species Homo sapiens. This is not, I hope, too controversial a statement. Furthermore, I assume that you are also a member of Homo sapiens. It is the scientific way of saying you and I are both part of the human race. However, what does that really mean? It seems clear that we are all human and yet, once you begin to pick at this statement, it becomes a bit less certain.

The two words Homo sapiens form just the last part of the biological taxonomic system that allows a scientist to nail down precisely what type of animal, bird, reptile or plant is being talked about. The system was invented back in 1735 by one of the great scientists of the eighteenth century, a Swedish naturalist called Carl Linnaeus. Linnaeuss work was in Latin, which is why biological names still use this language. The system starts with the Kingdoms of Life. You may think this would be the easy bit, but unfortunately everything in the Linnaean system of classification has undergone, and is still undergoing, periodic change. We started out back in 1735 with just two Kingdoms of Life: animals and plants. That number has since grown, shrunk, grown again, shrunk back and is currently standing at seven recognized Kingdoms of Life. Starting with the tiny things, we have the kingdom of Bacteria and the kingdom of Archaea, which are a distinct and primitive form of bacteria. The next kingdom of Protozoa is made up of all the single-celled creatures like amoeba, larger and more complex than bacteria. The kingdom of Fungi is fairly straightforward, although far bigger than you may imagine, and plants are now divided into the kingdom of Chromista, where you find the algae and seaweeds, and the kingdom of Plantae, where trees and grass and such can be found. Lastly is our own place, in the kingdom of Animalia.

Once you have found your kingdom, you work down through phylum, class, order and family before finally reaching genus and species. In our own case, after the kingdom of Animalia we are in the phylum Chordata, all of whose members have some sort of spine and spinal cord. We are in the class of mammals or Mammalia and following this comes the self-explanatory order of Primates. Then, our taxonomic family is Hominidae, or great apes, that only includes the various orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos or dwarf chimpanzees and ourselves, humans. Finally, we get onto the last two bits of our classification, our genus, Homo, and species, sapiens. Traditionally, so that they stand out in text, these two are always printed in italic and the genus is capitalized and sometimes abbreviated. The genus represents a very closely related group of different species. For example, Panthera leo is the lion and Panthera tigris the tiger. This double-barrelled naming system allows scientist to be precise and yet provide more information. Without knowing anything about Panthera onca, you can immediately gather that this species is probably some sort of big cat (its the South and Central American jaguar). Similarly, if I tell you the domestic cat is Felis catus, you can see it is not that closely related to the lion as the jaguar.

But what does all of this mean in practical terms? Our genus Homo contains just one species at the moment, and thats us. In the past, there have been more species in the Homo genus definitely another six and possibly another nine species on top of that but they are all now extinct. What is a species and how do we draw the line between them? It turns out to be a much trickier problem than you may imagine. When Linnaeus first concocted the idea, it was primarily just an aid in identifying different types of plant when you were out in the field doing some botany. The basic concept was that a species breeds true. Which is to say that if the offspring of an organism are the same as the parent they qualify as a species. Even with this simple definition, other scientists argued with Linnaeus and with each other about how to identify a species. One important implication of this idea is that species are fixed and unchanging.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Science of Being Human: Why We Behave, Think and Feel the Way We Do»

Look at similar books to The Science of Being Human: Why We Behave, Think and Feel the Way We Do. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Science of Being Human: Why We Behave, Think and Feel the Way We Do and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.