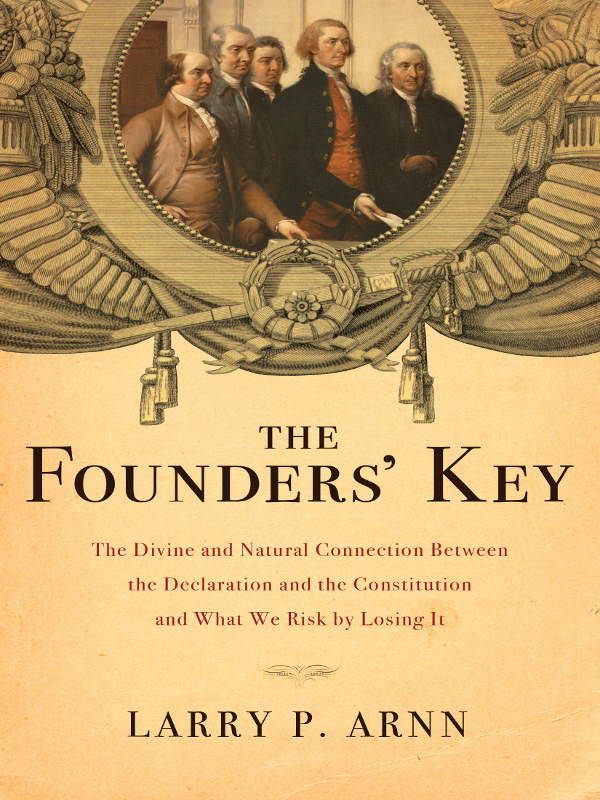

THE FOUNDERS KEY

The Divine and Natural Connection

Between the Declaration and the Constitution

and What We Risk by Losing It

Larry P. Arnn

2012 by Larry P. Arnn

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherexcept for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Thomas Nelson. Thomas Nelson is a registered trademark of Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Thomas Nelson, Inc., titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund-raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail SpecialMarkets@ThomasNelson.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Arnn, Larry P., 1952

The founders key : the divine and natural connection between the Declaration and the Constitution and what we risk by losing it / Larry P. Arnn.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-59555-472-7

1. United StatesPolitics and government. 2. Natural lawReligious aspects. 3. United States. Declaration of Independence. 4. United States. Constitution. 5. Constitutional lawUnited StatesReligious aspects. I. Title.

JK31.A76 2012

320.101dc23

2011041283

Printed in the United States of America

12 13 14 15 QGF 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Penny and our children,

Katy, Henry, Alice, and Tony

CONTENTS

Conclusion

by James Madison

PART I:

THE ARGUMENT

ONE

ETERNAL, YET NEW

The second day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.

John Adams writing to his wife on July 3, 1776,

the day after the Declaration of Independence

was adopted by the Continental Congress

IT IS NOT SO COMMON FOR NATIONS TO HAVE BIRTHDAYS. What is the birthday of England, for example? When did there begin to be a France or a China or an India? Old and wonderful places, their beginnings are lost in the mists of time. What they are today is connected to their past in ways we can hardly guess.

In the United States we have a birthday, the Fourth of July. This birthday is unusual simply for the fact of its existence, but also for another reason. On the one hand, it is a specific day, marked in memory of specific things done by specific people in a specific place. On the other hand, it is a day for the ages and for everywhere. What these people did, they did in the name of something universal and transcendent. In the combination of these two qualities, our birthday is unprecedented.

The story of our great nation has unfolded under the influence of this combination. Our great controversies and struggles have hinged on our allegiance to it. Our survival has sometimes hung by a thread of attachment to it. It does so right now. Our form of government, I will argue, was established in our Constitution to institute and to guard this combination.

The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution are commanding things for Americans because of this combination of features. On the one hand, they are ours, made by our own fathers. They provided the pattern according to which we have settled a continent and become a great nation, significant to all peoples. Our children, like our fathers and mothers, learn (even if not well) of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution as they grow up. The way we talk, the way we stand, the way we dance or singall are influenced by the laws of our land and the principles behind them, and our laws and principles spring from these two documents.

On the other hand, the document adopted on our birthday speaks with a voice far beyond our fathers and their particular situation, even though that situation was urgent to the point of life and death. Its language is so elevated that its meaning cannot be confined to the situation of its own time and place, to the situation of our own time and place, or to the situation of any time and place. This at least is what it says. If it is wrong about this, then it is wrong about the most important thing.

This universal feature of our birthday reinforces the strength of its calling. If your father gives you an instruction from your upbringing, and then he repeats that instruction in his will, this is powerful. If he himself has risked all that he has to sustain this instruction, and if he has lived his entire life in support of it, this is more powerful. If in addition this instruction claims that it is the right instruction, not just for his life and for yours, but for all lives and for all time, that is most powerful. And yet you cannot base your allegiance to the principle solely on the testimony of your ancestors. You must base your allegiance on the merits of the claim. You must adopt it because it seems sensible, and if it does not, you must discard itand with it your birthright.

This is the nature of the Declaration of Independence and of the Constitution written pursuant to it. They are our birthright. We Americans owe them a debt. They make a series of demanding claims. Although they leave plenty of room for adaptation to transient things, their core meaning is said to be absolute and fixed. To believe them is to take on the obligation to obey them, and then one must live in a certain way.

One can see how we might come to resent this burden. It is heavy. Its obligations come from more than one source, and therefore they command in more than one way. They command by blood, and they command by principle. They command with the authority of family, and they speak with the awesome force of nature and the God who presides over it. Who would blame us to ask why we should be trapped in this way? Our fathers were revolutionaries. Should we not be the same?

Moreover, we have made so very much progress from the time of the Revolution, from the time of the horse and buggy and the powdered wig. We face new challenges, but also we have all the new tools of modern science. Could we not come up with better principles than our fathers, just as we can now build taller and more momentous structures?

In relation to our beginning, our history has moved in two modes. Sometimes we have endeavored to embraceand sometimes we have endeavored to escapethe laws of nature and of natures God. They have been the source of our liberation, and they have seemed the source of our confining. Sometimes we would enjoy their blessings, but other times we would shrug them off as a curse.

Many of us today reject the universal and timeless claims of the Declaration, and therefore also we reject the forms of government established in the Constitution. We follow the notion, born among academics, that no such claim can be true and no such forms can abide. This belief is very strong among Americans now, and it has made vast achievements in changing our government. Because of this, we are near a moment of choice. This book aims to make clear the terms of that choice. The reader will not be surprised to learn that the author favors the keeping of the birthright, for its beauty and consistency, and for the failings of the alternative. Admitting this sharpens the obligation both of reader and of author to think as clearly, as truthfully, and as fairly as can be. We must do our best.

Next page