By Robert W. Black

Published by The Ballantine Publishing Group:

Appendix B

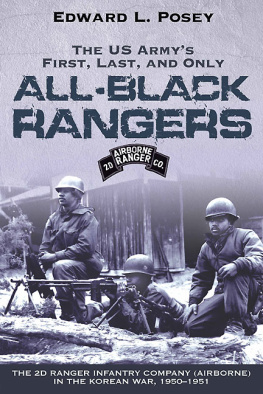

Insignia

At 1900 hours, Tuesday, 10 October 1950, the Department of Defense released a story titled Army Ranger Infantry Companies, Planned to Be Integral in Army Infantry Divisions, Was Announced Today by the Department of the Army. In terse sentences the plans for the rebirth of the Rangers was revealed. The final paragraph demonstrated that the Army was aware of recent Ranger history and wished to continue the tradition. The paragraph ran: Ranger Companies now being organized will be authorized to wear the shoulder insignia and otherwise continue the tradition of the Ranger outfits of World War II.

The red, white, and black scroll of the Rangers of World War II was highly respected, and the young men reporting for Ranger training were avid to win and wear the scroll. Plans came to a sudden stop, however, when a Washington-based staff officer discovered that the famous World War II insignia of the Rangers had never been authorized, and that another insignia, little known and less preferred, was what the Army had approved.

The story goes back to the year 1942, when Maj. William O. Darby, commanding officer of the 1st Ranger Infantry Battalion, sought a shoulder insignia worthy of his unit. He announced a contest, with an award of twenty-five dollars for the best design. A member of the Battalion Headquarters Company, Sgt. Anthony Rada of Flint, Michigan, won the prize with a design that featured an arc or scroll with a black background, red trim, and the inscription 1st RANGER BATTALION in white letters. The shape was based on the commando arc and demonstrated the close bond between the Rangers and commandos.

Why the colors black, red, and white were chosen is unknown, but some early reporters thought the black was actually dark blue and the colors of our flag had been selected. The Rangers, however, were insistent the color was black. One former Ranger said the colors were taken from the Nazi flag and were a calculated insult to Hitler. They intended to jam them down the Germans throats. The 1st. 3rd. and 4th Ranger battalions were proud of their scroll and wore it whenever permitted. They tried to get it approved, but the wheels of bureaucracy turned too slowly and approval did not come through.

On 1 April 1943 at Camp Forrest, Tennessee, the 2nd Ranger Battalion was activated. On 16 July 1943 the War Departments Services of Supply Headquarters published memorandum SPRMD 421.4 (19 June 43), the subject of which was, Distinctive shoulder patch. The memorandum stated that by order of the Secretary of War, all Ranger battalions in existence or in the future would wear a diamond-shaped blue patch bearing the word Rangers in gold-colored letters. The patch was to be also edged in gold. The blue diamond insignia met with disfavor. It resembled the gasoline sign of a blue Sunoco station, and when men wore the patch, other soldiers referred to them as Gas Troopers. This resulted in frequent fistfights.

When the 2nd and 5th battalions arrived in Europe, they began to wear the unauthorized insignia of the 1st, 3rd, and 4th battalions, adding only their distinguishing number. The 5th Ranger Battalion liberated a large number of German marks from a German paymaster, and with these they employed a group of nuns to make their scrolls.

When the 6th Ranger Battalion was formed in the Pacific, it too adopted the red, white, and black scroll designed by Anthony Rada. All the Ranger battalions of World War II wore the scroll, even though it was not authorized.

In 1947 the Army abolished the diamond-shaped insignia, leaving nothing approved for the Rangers. (No Ranger units were then on the Army rolls.) When, in 1950, the need for Ranger insignia returned, there was no approved insignia to turn to. In the eyes of those who were volunteering, the scroll was the oldest Ranger shoulder insignia and had the approval of the men.

Sometime around 19 September 1950 Colonel Van Houten made a visit to the Pentagon to discuss Ranger insignia with a representative of G-1. Van Houten did not like the diamond-shaped patchhe wanted an arc-type tab. Van Houten was equally opposed to an individual unit designation; he sought to build pride in being part of the Ranger family, rather than in being in an individual company. An arc tab was finally agreed upon, but G-1 wanted only a tab that said Ranger. Van Houten felt that as Airborne was a separate qualification, there should be a tab for each. He specifically desired an insignia with the word Ranger in white letters on a black background with red border. Most important to Van Houten was that the approved insignia be ready for issue to the first class of graduating Rangers on 13 November 1950.

The insignia design was done on a rush basis, and on October 30 the Department of the Army, G-1, informed Colonel Van Houten that the approved Ranger arc would be 2 3/8 inches wide and half an inch thick; the base color would be black with a yellow border and yellow lettering (later changed to gold). The word Airborne would also be authorized for wear.

The insignia did not find favor with the initial Ranger companies of the Korean War. Orders were that the black and gold Ranger tab would be worn above the division insignia of the division to which the company was attached. Even before the first companies had departed from Fort Benning, the shops of Columbus were selling a red, white, and black scroll that showed the company number and the word Airborne.

Those companies that served with divisions in the U.S. or that were under close watch by the inspector general wore the black and gold tab over the division (or Army) insignia while on duty. Those in Korea wore the black and gold Ranger tab stitched on their soft caps, but the scroll insignia was procured when men went on leave to Japan and worn on the shoulder.

The colors were not always consistent. The 1st Ranger Company sported a black and gold Airborne Ranger scroll. By the time the units were inactivated, red, white, and black with the company number was the norm. This insignia proliferated when the men were transferred to the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team at Beppu, Japan, and men could show their combat insignia on their right shoulder.

The red, white, and black scroll was now standard for those Rangers who served in Korea and those elsewhere who could get away with wearing an unauthorized patch. The Japanese merchants made an additional change. They frequently found themselves with a large stock of patches with one company number on it, and out of stock on the number the customer desired. The Japanese resolved this by removing the company number and inserting INF. Thus the patch read Airborne Ranger Infantry Company.

Many men who served as Rangers during the Korean War looked upon the black and gold Ranger tab as a qualification badgea demonstration that they had graduated from a particular form of trainingrather then as a unit insignia. The Army reinforced this view when the Ranger Department was formed on 10 October 1951. Army regulations of 23 January 1953 announced the tab, and in its 1965 Army regulation 672-5-1 instructed: the Ranger tab is a qualification shoulder sleeve insignia, therefore it is not authorized for wear on the right shoulder. Most Rangers who served in Korea wore their red, white, and black scrolls on their right shoulders in defiance of the inspector general. Later, in Vietnam, Rangers would once again wear the red, white, and black scroll.

In 1983 the Ranger veterans of the Korean War began a movement to win official recognition of this traditional Ranger insignia. The Rangers on active duty requested the change be made, and in 1984, and with the formation of a Ranger regiment, the traditional insignia of the Rangers finally became authorized.