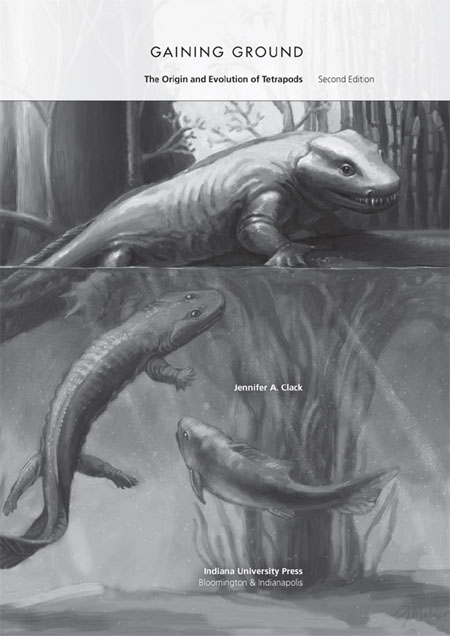

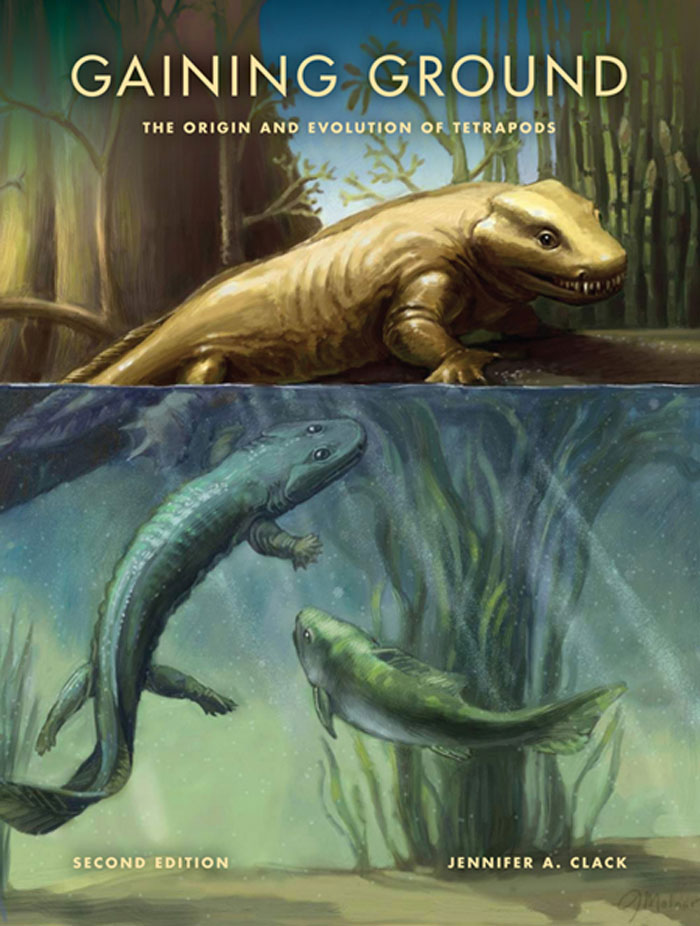

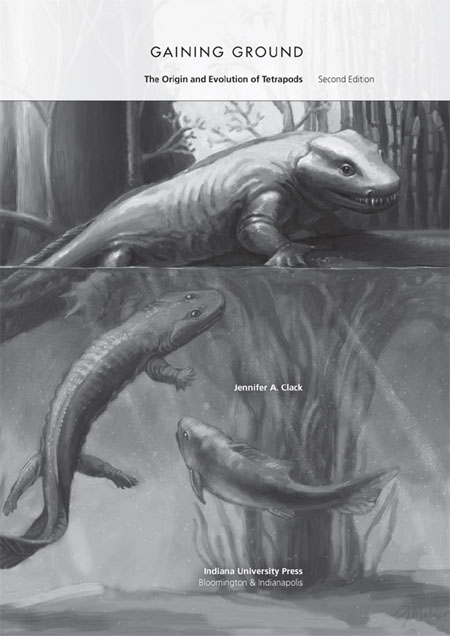

GAINING GROUND

Life of the Past James O. Farlow, editor

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47404-3797 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

2012 by Jennifer A. Clack

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the

United States of America

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Clack, Jennifer A., 1937

Gaining ground : the origin and evolution of tetrapods / Jennifer A. Clack. 2nd ed.

p. cm. (Life of the past)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-253-35675-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-253-00537-3 (e-pub) 1. Lungfishes, Fossil. 2. Amphibians, Fossil. 3. LegEvolution. 4. Paleontology-Devonian. 5. PaleontologyCarboniferous. I. Title.

QE852.D5C57 2011

1 2 3 4 5 17 16 15 14 13 12

Contents

Preface to the Second Edition

Since the first edition of Gaining Ground was completed, much has happened in the field of early tetrapod paleontology and in the wider world that has affected not only the ideas and conclusions presented in the first edition, but also what paleontologists are able to do with material, the techniques that they use, and how easily and quickly things can be done.

One of the most significant events worldwide has been the global spread of the Internet, which has not only allowed discoveries to be published more quickly, but has enabled rapid searches for material and references. The ease and speed of access to references by electronic means and Internet search have improved enormously, allowing information and citations to be readily found at the touch of a button. Its hard to remember that in the late 1990s and the first couple of years of the 21st century, when the first edition was written, online connections were often slow and limited. Today, the ease and availability of electronic techniques has greatly affected many aspects of producing and delivering a wide range of scientific output. I personally have been most affected by my familiarity with software packages such as Photoshop, which permits manipulation of scanned images to produce diagrams. Some of the diagrams in the first edition were admittedly clumsy, and I hope that readers will find these improved in the second. Digital photography, of course, is another boon.

Technological advances have affected many areas of study, and paleontology is no exception here. One of the techniques that has improved in availability, cost, and degree of resolution is that of X-ray computed tomography (CT), or micro-CT scanning. This is becoming the technique of choice for examining new aspects of fossil material previously inaccessible. Software programs build the serial sections produced by scans into three-dimensional images that can be easily manipulated and dissected. These have become more sophisticated but at the same time more amenable to being run on a moderately powerful desktop computer, as well as becoming more intuitive to use. Such advances have allowed new questions to be framed and answered. One stage up from micro-CT scanning with X-rays is the use of a synchrotron. This allows minute examination of tissue structure inside fossil material, from which, for example, three-dimensional images of growth patterns of bone can be built. For really high-resolution scanning to get these results, at present, the limitation of this technique is the small size of sample that can be examined at any one time. Larger specimens can be scanned at lower resolution, often higher than with micro-CT machines, but results still depend on the geological makeup of the material.

Micro-CT images of fossils are increasingly being used in biomechanical studies using an engineering technique known as finite element analysis (FEA). This allows study of the relative degrees and directions of stress that a structure, such as a skull, can withstand, thus permitting function to be inferred. Although FEA has not yet been widely applied to very early tetrapods, such analysis of lower jaw function, for example, should help reveal what the implications are for the changes in dental patterns seen across the fishtetrapod transition. Such work is in progress.

Digital imaging and suitable computer programs allow quantitative studies of, for example, skull proportions, or the way in which different bones contribute to skull structure in different groups. This study, known as geometric morphometrics, is being applied to groups of fossil tetrapods. It can help tease apart differences in shapes among a range of taxa to reveal phylogenetic or morphological relationships, and some of the results are included in this new edition.

New electronic techniques have also been brought to bear on climate modeling and atmospheric composition in past periods of Earths history, and these are highly relevant to understanding the late Paleozoic and events that occurred during that time.

Computers increased memory, faster processing power, and lower cost have allowed increasingly large data sets of taxa and characters to be used in phylogenetic analyses, and new search protocols and methods are beginning to provide alternative ways of processing the information. Some of these advances have been made in the field of molecular phylogenetics and in the incorporation of morphological and molecular data into combined analyses.

Cladistic matrices and the trees they generate are now being interrogated further in metadata analyses to produce hypotheses of overall evolutionary patterns: diversity and disparity curves, effects and results of evolutionary constraints or restrictions on taxa, episodes of character release (i.e., increasing the number of potentially varying characters) or decreased rates of character change, evolution of body size among clades, and many others (e.g., Ruta et al. 2006; Wagner et al. 2006; Laurin 2004).

The electronic age has seen a veritable explosion of information in the field of evolutionary developmental biology, or evo-devo. In its infancy in the early 1990s, it has more recently been asking questions in a phylogenetic context, incorporating ideas and data from phylogenies that have been drawn by means of both molecular and morphological data and that include fossil taxa. Paleontology has much to contribute to that endeavor, but similarly, researchers in evo-devo fields have been addressing questions on the basis of phylogenetically relevant species. Sharks, lungfish, and nonteleost fish are examples of these species, which have provided key information in studies such as the origin of limbs and digits.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.