The Bare Bones

Life of the Past

James O. Farlow, editor

THE BARE BONES

An Unconventional Evolutionary

History of the Skeleton

Matthew F. Bonnan

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2016 by Matthew F. Bonnan

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bonnan, Matthew F.

Title: The bare bones : an unconventional evolutionary history of the skeleton / Matthew F. Bonnan.

Description: Bloomington : Indiana University Press, 2015. | Series: Life of the past | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015020766| ISBN 9780253018328 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780253018410 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: SkeletonEvolution.

Classification: LCC QL821 .B66 2015 | DDC 599.9/47dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015020766

1 2 3 4 5 21 20 19 18 17 16

TO MOM AND DAD without your early encouragement, this would not have happened.

MY CHILDREN, QUINN AND MAXWELL may you always appreciate and respect the vertebrate animals that form our greater family tree.

JESS BONNAN-WHITE as always, for your love and support.

So have a toast and down the cup, and drink to bones that turn to dust.

OINGO BOINGO, No One Lives Forever

Everybodys got mixed feelings about the function and the form.

RUSH, Vital Signs

Contents

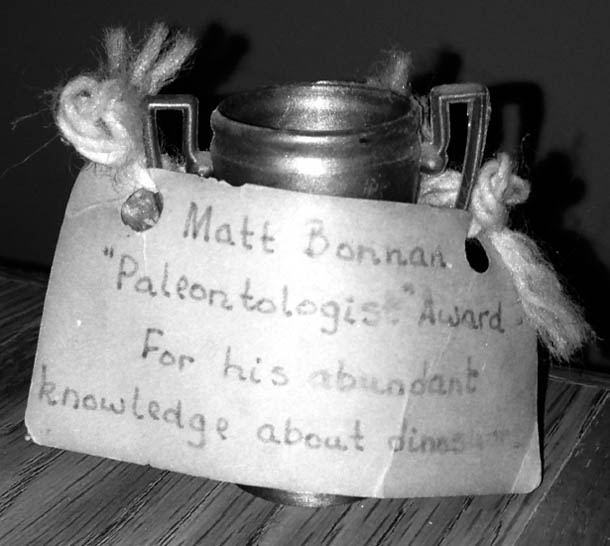

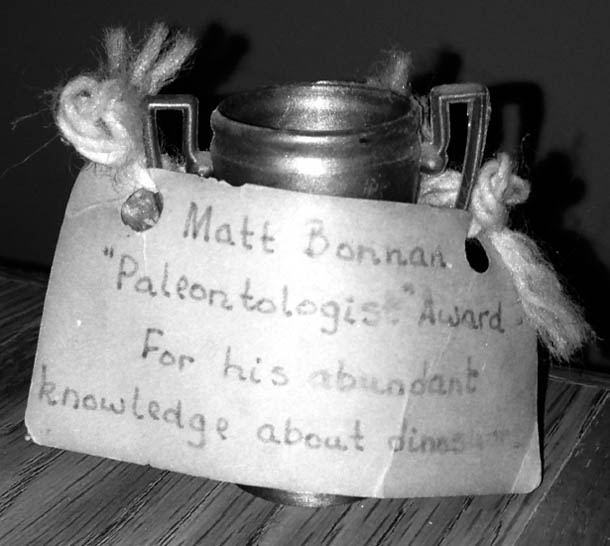

The authors first paleontological award.

Preface

I DONT KNOW WHY IT STRUCK ME, BUT IT DID WITH SUCH FORCE that my lifes trajectory was forever changed. Im speaking, of course, about my passion for dinosaurs, big dead reptiles that have captivated me since the tender age of five. I was that annoying kid in the first-grade classroom who knew all the dinosaurs and corrected the teachers on their pronunciation. I was even given a Paleontologist Award by my first-grade teachers for my, ahem, abundant knowledge about dinosaurs. I did have varied interests outside of dinosaurs, including everything from human anatomy to science fiction to role-playing games to music editing (Im not suggesting these were cool interests). In fact, I even did a stint at a radio station in college (WDCB, Glen Ellyn, Illinois), where I played songs that sounded interesting (at least to me) in headphones. Yet, over time, the allure of fossils kept its pull.

I was never so much into the treasure-hunter aspect of paleontology, but rather the thrill of reconstructing long-dead animals and breathing life into old bones. In other words, I am a zoologist and anatomist at heart who happens to be fascinated by dinosaurs. I see dinosaurs as living animals, and I want to reconstruct how these animals moved and behaved when their bones were still pulsing with blood. As time has gone by, I have come to have a deep appreciation and fascination with all the backboned (vertebrate) animals, their collective natural history, and their evolution. I have come to realize that the questions about dinosaurs that I began to pursue in earnest in graduate school have a broader and more powerful context across our vertebrate family tree.

I was inspired to write this book when I began teaching my own vertebrate evolution and paleontology course for undergraduate students. What I found was that many of these students were fascinated by vertebrate evolution, but that few, if any, went on to careers in museums and academe. Instead, many of my students were future teachers, doctors, veterinarians, and perhaps even politicians. There are many excellent books available on vertebrate paleontology, many of which I consulted in writing this book, but their focus tends to be strongly taxonomic and linearly chronological: who is who, who is related to whom, and in what order do we find them. However, the books that had truly inspired me to become a paleontologist were those that tackled the issue of functional morphology and paleobiology: what does the skeleton tell us about how the animal moved, fed, and behaved? This is the type of questions that motivated me as a student to learn about vertebrate history.

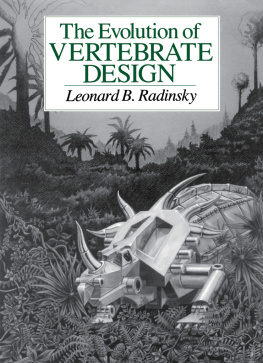

During my formative years and into my undergraduate days, I read a number of books that inspired the more colloquial approach I take here. First and foremost, The Dinosaur Heresies by Robert T. Bakker, After Man: A Zoology of the Future by Dougal Dixon, and Archosauria: A New Look at the Old Dinosaur by John C. McLoughlin were the books that truly lit the fires of my imagination in junior high. The stories these books told about past life or possible future evolution, combined with engaging artwork, solidified my desire to be a professional scientist. I even corresponded with Dougal Dixon, and his letter of encouragement to a thirteen-year-old budding paleontologist was inspirational. However, during my undergraduate days, I stumbled upon a small book called The Evolution of Vertebrate Design by the late paleontologist Leonard Radinsky that would truly influence my approach to writing. Radinsky took a complex subject like vertebrate paleontology and, using cartoons and brief but informative language, distilled the essence of our evolutionary story into a format that was friendly and approachable. In fact, I initially used his book in my vertebrate paleontology and evolution courses because it served as a jumping-off point for exploring the rich tapestry of vertebrate life past and present.

Given that Radinsky passed away in 1985, his beautiful book was never updated. Despite its appeal to my students, with each passing year the stack of articles I was assigning to supplement the understandably dated material was becoming larger than the book itself! Simultaneously, as my research developed into understanding the evolution of dinosaur locomotion, I was beginning to question why I had never paid more attention to classical mechanics in my physics courses. When I took physics, I found the course to be absolutely dull and dry. However, if you can understand the way that the machines and tools that surround us in our daily lives work the way that they do, you can approach the skeleton the same way. And then I thought, what if I tried to write a book about the evolution of the vertebrate skeleton as if I were someone trying to teach my younger self about classical mechanics and physics? Using Radinskys book as an inspiration and launch point, I began writing the book you now hold in your hands: what I hope is a friendly but somewhat unconventional introduction and exploration of the history of the skeleton, using machine metaphors, for those who want to learn but do not (yet) have the chops for anatomy.

Next page