CONTENTS

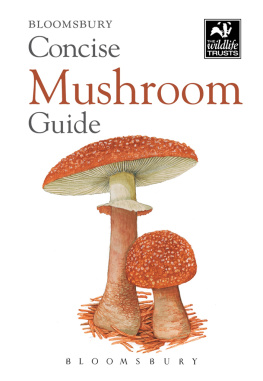

Although practically everyone realises that the mushrooms they see in the supermarket are fungi, relatively few shoppers know how they fit into the overall scheme of living things, and how they are related to the fruit and vegetables nearby on the same shelf or to the animal carcasses on the butchery and fish counters. The truth is that mushrooms are not related to either, although there has been a tradition of teaching what little is taught about fungi in plant science rather than animal science courses largely because, like plants, they often grow from the soil and do not move. It is now recognised, however, that living things can no longer be placed in two simple Kingdoms of plants and animals. Over the past fifty years, others have been added, and for some time Fungi have been referred to as the Fifth Kingdom, although some of the latest scientific thinking recognises six or even more to accommodate the wide range of microscopic organisms now known to exist. Nonetheless plants and animals are still the major groups with which most people are familiar.

Fungi are not related to plants or animals because they differ from them in many important ways. Whereas the basic structural elements of plants and animals are cells which, en masse, form tissues, fungi are built up of uniquely different microscopic tubular thread-like bodies with multiple nuclei called hyphae; and collectively hyphae form, not tissue, but mycelium (although the word cell is used widely in relation to small fungal structures that look like cells). The reproduction of fungi also differs greatly from plants in that they produce, not seeds, but microscopic structures called spores.

Fungi are also uniquely distinct in relation to their mode of nutrition. Plants photosynthesise, a process in which solar energy is absorbed by green chlorophyll and used to bring about the formation of nutrient substances from the raw materials of atmospheric carbon dioxide and water. No fungus can photosynthesise, and even the few species that sometimes display a green fruit body colouration or green spores do not contain chlorophyll. Fungi also have a mode of nutrition different from animals in that while animals eat, digest and then absorb the digested matter internally, fungi secrete enzymes externally from their hyphae into the environment where organic matter is broken down and then absorb the resulting chemicals from there. Like animals therefore, fungi are dependent for their nutrient source on other organisms, either living or dead. And this dictates where they grow: typically on soil, using humus and plant remains for nutrition; directly on wood or other plant matter; or sometimes parasitically on still living plants.

Fungal nutrition is a complex subject but one aspect of it is nonetheless of particular importance in relation to their occurrence in the field. Anyone who has ever collected toadstools will have noted that many, perhaps most, occur in particular types of woodland, beneath particular types of tree or consistently in company with certain types of plant. This is not mere chance, nor the result of two species requiring a similar ecological niche. It is because of an intimate association called a mycorrhiza, which means that under certain circumstances the one cannot exist, or can do so only inadequately, without the other. A mycorrhiza is a symbiotic association between fungal hyphae and the roots of higher plants, and also, to some extent, of some Pteridophytes (ferns and their allies) and the rhizoids of Bryophytes (mosses and liverworts). The fungal mycelium forms an outer sheath around the fine rootlets and this can be seen if the rootlets are examined closely with a lens. Penetration of fungal hyphae into the root is limited and occurs only between the cells of the cortex. Precisely how the mycorrhizal mycelium assists its host plant, and vice versa, is still imperfectly understood, but it seems that the fungus obtains much of its necessary supply of carbon from the roots and, in return, acts as an intermediary in the uptake of nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphate and potash from the soil. The mycorrhizal fungus seems better able to achieve this uptake, especially from poor soils, than does the plant acting on its own.

The naming and classification of fungi

Living organisms are given names and are classified into groups; fungi are no exception. The scientific names used for organisms today are based on a binomial or two-name system based on Latin and other languages and using Latin grammar derived from one devised by the Swedish biologist Linnaeus (Carl von Linn, 17071778). The binomial of each organism does more than signify its uniqueness, however, as it also attempts to indicate its relationship to other similar forms. Whilst each group of basically identical individuals is called a species, designated by the second of the two names, the larger groups to which similar species are considered to belong are called genera (singular genus) and it is the genera that contribute the first name. So, the fungus genus Lepiota includes species like Lepiota lilacea, Lepiota magnispora and Lepiota obscura. The specific or trivial name often attempts to give some information about the organism, for example lilacea signifies a lilac-coloured fungus and magnispora one with large spores, although sometimes, as in obscura, it does no more than recognise some undefined peculiar feature.

The category above the genus is the Family and above that is the Order. Names of families always have the ending -aceae. Names of orders end in -ales and above them in the fungal taxonomic hierarchy is the Subclass ending in -mycetidae and the Class, ending in -mycetes. A few fungal scientific names have given rise to widely used general terms. The name agaric is often used to mean any fungus with a shape roughly like most of those in the Order Agaricales the familiar umbrella-like toadstools with gills beneath the cap. A bolete is a comparable toadstool with pores like those in the Order Boletales, especially the family Boletaceae, while a polypore is any fungus belonging to the Phylum Basidiomycota (apart from the stalked, toadstool-like boletes) that discharges its spores through pores and not from gills; most of them are bracket-shaped. Finally, a corticioid fungus is one that forms a thin, skin-like, fibrous or membranous fruit body, usually growing on wood it takes its name from the Order Corticiales to which many of them belong.

Fungi are able to exploit most of the natural and many of the artificial raw materials of the world as nutrient sources; and to tolerate most of the environmental variables the earth can offer. Of all the natural habitats able to support life of any type, almost all are inhabited by some species of fungi. But whilst many genera of larger fungi certainly occur predominantly in one type of habitat, there are few that are wholly characteristic of individual types of woodland, grassland or other community. Nonetheless, there are certainly some fungal genera, and, more significantly, some associations of genera, that do give each habitat a characteristic mycobiota. Amanita, Lactarius and Russula for instance, which are mycorrhizal associates of trees, are predominantly woodland genera, while Hygrocybe is usually found in grassland. And a species list including Mycena capillaris, Russula fellea, Craterellus cornucopioides and Boletus satanas conjures up an image of a beech wood to a mycologist in much the same way as a list including bramble, dogs mercury, foxglove, holly and violet helleborine might to a botanist.