Table of Contents

For Donna, Elise, Andre, Stephane and Gabriel

Liquor went out across the Great Lakes region to the hot spots of Chicago, Buffalo, and Cleveland. The towns of Leamington, Belle River, Wheatley, Port Lambton all funneled liquor across to the U.S.

(Drawing by Peter Frank of Gale Research)

Foreword

The peaceful Detroit River. A great centre fielder might just be able to throw a baseball across, Windsor and Detroit are that close. Roy Haynes, U.S. Prohibition Commissioner, said there was no better spot than the Detroit River for smuggling liquor. The Lord probably could have built a better river for rum smuggling. But the Lord probably never did!

The Detroit River became the primary transfer point for Canadian liquor and beer into Michigan, Ohio and points further afield. And Windsorites took almost immediate advantage of the opportunities Prohibition presented. In the first days of Prohibition, Canada Customs noticed a huge increase in the demand for motorboat licences, and issued a warning that contraband liquor might soon find its way across the rivers and lakes into the U.S. In the first seven months of 1920 the start of Prohibition more than 900,000 cases of liquor were shipped to the Windsor area for what was termed private consumption. Sure enough, in one week alone in May 1920 the police court collected more than $10,000 in fines from rumrunners.

It became evident that a new age had been born, and as Larry Englemann writes in Intemperance , the Prohibition dream had become an American nightmare. It was also a wild and hysterical period, that ushered in its own language speakeasies, flappers, rumrunners and introduced a colour and excitement difficult to match at any other point in recent memory. It left its mark on the memories of everyone who lived through it. If you werent involved in the actual traffic of liquor, you were buying and drinking it. If you werent drinking, you were campaigning against it. If you werent parading and carrying placards, you were privately sipping ale with cherished delight.

Some recall it with a smile and a wink. You can almost hear knees being slapped at the telling of these stories, brimming with exaggeration, a blend of gossip and fact, blessed with an affinity for the spectacular.

These are the reminiscences of people who guided jalopies across the ice, carting wooden crates of bourbon and good Canadian whiskey to blind pigs and warehouses on the American side; of those wide-eyed bystanders who unobtrusively stood at a counter drinking shots, trying to catch the eye of some giggling gal with kiss curls who kicked and waved on the glistening ballroom floor of a border roadhouse; of the people who paid dearly for the occasional bottle from someone who was reputed to be associated with the masterminds behind the liquor trade; of the innocent participants from that era who had an Uncle Jake and Aunt Gertie who kept a healthy supply of booze under the floorboards of the back shed.

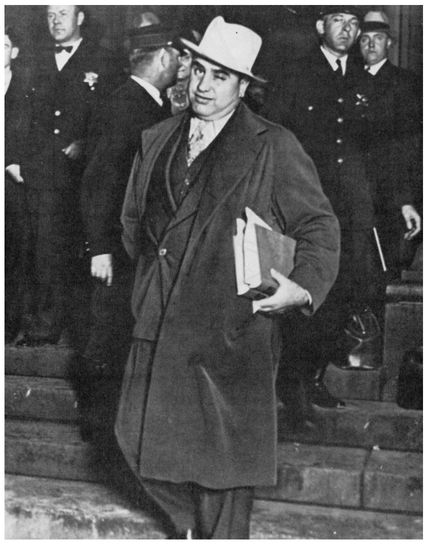

Al Capone developed most of the rumrunning activities in the United States, and is said to have accumulated up to $100 million per year from contraband beer sales alone. He is said to have engineered countless killings, but when finally sent to prison in 1931, it was for tax evasion.

All of these characters have an exclusive flag over the territory in their memory they call the Prohibition Era.

The liquor being sold in the U.S. was for the most part smuggled across the border from Canadian ports. The majority of this passed through Windsor, or the Border Cities, as the ports surrounding Windsor were then called. Police estimated that nearly four-fifths of all the liquor smuggled into the U.S. passed across the Detroit River. The traffic was so heavy and frenetic that this route came to be known as The Windsor-Detroit Funnel.

One would have thought Prohibition would have put an end to liquor consumption, but it had just the opposite effect. Less than a year after its introduction, the per-capita consumption jumped from a pre-war level of 9 gallons to 102 gallons. This liquor, of course, wasnt for private use, but was shipped across the river to blind pigs and warehouses.

One Windsor widow, who lived on Pitt Street, just one street up from the Detroit River, was suspected by the police of selling liquor to smugglers. She had purchased forty cases of whiskey and nine barrels of liquor over a six-month period. Upon being brought to court, the protesting woman said she had taken up serious drinking since the war and now downed at least five quarts of whiskey daily. The magistrate proved unsympathetic and ordered police to confiscate the remainder of her household supply.

Though Prohibition failed, for the owners of the blind pigs, for the bootleggers, the rumrunners, the gangsters, the roadhouse proprietors, the police, the magistrates, the spotters, the boaters and armies of others, it was a roaring success. It meant work. Employment. Easy money. Cash in the pocket. Good times. Shiny new cars. New suits.

But these bootlegger tales by no means eclipse the recollections of the hard-driving temperance soldiers who worked tirelessly to win the battle against strong drink, who actively campaigned to bring in the laws that put liquor under lock and key and hoped to eradicate Demon Rums ugly effects, which they claimed destroyed not only minds but families. For them those in The Dominion Alliance, the Womans Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), the Womens Legion for True Temperance, the staunch and pompous Methodists, the saloon busters and the angry evangelists Prohibition represents lost years, fatal years. Little did the enemies of moonshine and the saloons realize that by putting liquor out of the reach of the general population, they had in effect created a monster. For instead of society turning reflectively upon itself to ponder the common good, as they had hoped it would, it plunged itself headlong into one of the wildest, most violent and colourful of times the Roaring Twenties.

It was during this era that North America gave birth to some of the largest crime syndicates and most vicious criminals. It was a time when Al Capone, Bugs Moran, Johnny Torrio, the Purple Gang, Pete Licavoli, and the Little Jewish Navy (sometimes called Jew Navy) became household names.

Unemployment during this period became a myth as legions joined the forces of both the temperance groups and the bootlegging industry. As an example, Detroit boasted that during those years, sales related to liquor profits from smuggling and in blind pigs made booze the second largest industry in that city, exceeded only by the manufacture of automobiles. The Detroit Board of Commerce speculated that more than 50,000 people were involved in the booze business. Actual sales of over the counter liquor in Detroit amounted to more than $219 million, while wine sales surpassed $30 million.

The number of people working in the liquor trade in Canada is much harder to estimate, but in the early days of Prohibition, it was said that 25% of the population near the Detroit River was involved in booze smuggling. Nearly a quarter of a million dollars was collected in fines by Windsor courts from boaters illegally possessing liquor during the first seven months of 1920.