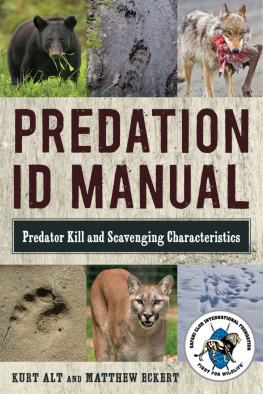

Copyright 2017 Kurt Alt and Matthew Eckert

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Tom Lau

Cover photo credits: iStockphoto

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-2251-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-2242-2

Printed in China

Contents

Purpose

THIS FIELD MANUAL is designed to help anyone determine whether an animal was killed by a large predator and which species was involved with the predation event.

It intends to improve the accuracy of identifying the predator responsible for killing an animal.

It intends to improve consistency among those using this manual when investigating predation events.

It intends to clarify and define the terminology used in classifying a predation event.

Ultimately, this manual intends to improve our understanding of predator-prey relationships, to inform science-based wildlife management decisions.

Acknowledgments

SAFARI CLUB INTERNATIONAL Foundation (SCIF) and the SCIF Hunter Legacy Fund sponsored the production and publication of this manual, demonstrating one of the many contributions hunter-supported conservation organizations have made to wildlife research and management.

Dr. Jerry Belant, Dr. Harold Picton, Jim Hammill, Dr. Bob Inman, and Dr. Jon Swenson provided key insight and review of portions of this manual. We thank Dr. James Halfpenny for key final content edits and graciously allowing the inclusion of thirteen pages from his 1986 publication, A Field Guide to Mammal Tracking in North America.

We thank those field professionals who from their years of experience, unselfishly and collectively contributed the content for this manual, providing a useful tool for those in the field conducting wildlife management and research. The basic knowledge and insight found in this manual was contributed from the following wildlife professionals:

Matthew Lewis, Director of Conservation, Safari Club

Bryan Aber, Carnivore Biologist, ID Fish and Game

Liz Bradley, Species Management Specialist, MT Fish, Wildlife & Parks (MTFWP)

Mark Bruscino, Large Carnivore Program Supervisor, WY Game and Fish

Peggy Callahan, Executive Director, Wildlife Science Center, MN

Kevin Frey, Species Management Specialist, MTFWP

Steve Gullage, Senior Programs Manager, Conservation Visions Inc.

Dr. Al Harmata, Affiliate Faculty, Montana State University

Ben Jimenez, Bitterroot Elk Ecology Project, MTFWP

Jamie Jonkel, Species Management Specialist, MTFWP

Nathan Lance, Species Management Specialist, MTFWP

Larry Lewis, Wildlife Technician & Fish and Game Peace Officer, AK Fish and Game

Shane Mahoney, President and CEO, Conservation Visions Inc.

Tim Manley, Species Management Specialist, MTFWP

Dr. Kerry Murphy, District Biologist, Bridger Teton NF, US Forest Service

Abigail Nelson, Species Management Specialist, MTFWP

Dr. Jennifer Ramsey, DVM, Wildlife Veterinarian, MTFWP

Dr. Tom Roffe, DVM PhD, Chief of Wildlife Health, US Fish and Wildlife Service

Mike Ross, Species Management Specialist, MTFWP

Dr. Toni Ruth, Research Scientist, Selway Institute

Dr. Doug Smith, Wolf Research Project Leader, Yellowstone National Park, US National Park Service

Dr. Frank van Manen, Supervisory Research Wildlife Biologist, Team Leader Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, US Geological Survey

Jennifer Vashon, Wildlife Biologist, Species Specialist for lynx and black bear, Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife

Preface

Understanding the relationships between predators and prey is essential for wildlife managers to make science-based decisions with managing wildlife.

Shane Mahoney, personal communication

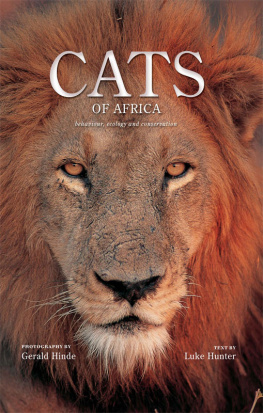

OUR UNDERSTANDING OF predator-prey dynamics is often limited by our inability to accurately identify what species of predator is responsible for killing prey. This understanding is crucial when developing management strategies for both predator and prey populations. It is also important for effective management of livestock depredation. While this manual may have multiple applications, it strives to distinguish the signs left by different large predators when killing and consuming wild prey.

It is unreasonable to expect even the most experienced biologists to solve every wildlife predation mystery at the scene of a kill. When an investigation of a kill site fails to solve the mystery, the upshot is commonly noted as Unknown Predator. The higher the percentage of kill sites in the same study or ecosystem noted as Unknown Predator, the lower our confidence becomes when concluding what predator species is dominant. Knowing to what extent a predator is dominant is central for estimating its holistic impact on a prey population. Our science-based approach in managing wildlife in predator-rich systems drastically improves when we understand the role of each predator. Thus, the more mysteries we can solve, the better, and the more guidance we have to solve the mysteries, the better. This manual consolidates the expertise of twenty wildlife professionals with over 420 years of collective field experience and offers it to the next generation of biologists to build on.

Introduction

FIELD BIOLOGISTS INVESTIGATE kill sites of animals to better understand the interactions between predators and prey. Mentally recreating the predation event from the stalking predator at a vantage point, the chase, the kill, and how the protein reward is consumed is exhilarating. Biologists live vicariously through this raw reality of nature and have their own glimpse at what it means to be wild.

While exciting, recreating a predation event only from sparse clues left behind is difficult and can be frustrating. Investigators spend hours second-guessing themselves while exhausting every possibility from inconclusive evidence. Nonetheless, the purpose is important, and in the end, each biologist is working towards a goal of improving the science in wildlife management.

Wildlife managers must consider many factors affecting wildlife, including cause-specific mortality from disease, starvation, trauma, and predation. Insights into causes of mortality are time consuming and expensive to obtain, yet essential in developing successful wildlife management strategies. Fortunately, cumulative knowledge and technological advancements have dramatically improved our ability to determine how and why an animal died.

Traditionally, physical evidence found on and around a carcass was used to determine whether and how an animal was killed. Commonly used evidence included age and condition of prey, signs that the animal was killed and consumed, prey caching, habitat type, hair samples, footprints found at the site, and so on. Since the late 1990s, our understanding of predator behavior has been enhanced through increasingly sophisticated research techniques. DNA technology now allows us to determine species involved by obtaining saliva samples from puncture wounds. Innovations in technology from GPS, mortality sensors, vaginal implant transmitters, micro transmitters that can be placed on neonates, trail cameras, and so on have allowed wildlife professionals to more fully understand and accurately assess predation at kill sites. However, even with technological advancements, the basics of field investigation are as important today as they were thirty years ago. Technology cannot replace how the human brain can collect all the clues to recreate the events that transpired at a kill site. We invest in new technology because it provides tools and information to improve our ability to conduct consistent and accurate kill site investigations.