Table of Contents

PRAISE FOR THE FIRST EDITION

Hart and Sussman have written a highly readable book, with jazzy subtitles such as Will the First Hominid Please Stand Up?, Before the Age of Ulcers, and My, What Big Teeth You Have! Their argument that human beings and their predecessors, during almost the entire period of their evolution, have been preyed on rather than predators is entirely persuasive.American Anthropologist

Donna Hart and Robert Sussmans observations of how living primates cope with constant threats bring to life their interpretation of our extinct human relatives and ancestors, along with the role that predation has played on our social and cognitive evolution. Surprise, surprise, it has always paid to have friends and allies.New Scientist

Hart and Sussmans book presents a good synthesis of pertinent ethological observations and a summary of theoretical framing, along with a healthy dose of anecdote.Evolutionary Anthropology

Man the Hunted... is accessible and interesting.... The authors describe and debate the common view of Man as the evolving hunter and present their own view of Mans evolution as an adapting prey by integrating fossil records and behavioral data from living predator-prey interactions involving human and nonhuman primates.

American Journal of Human Biology

Contrary to the familiar image of the aggressive, spear-wielding caveman, our hominid ancestors were more hunted than hunters, more preyed upon than slayers of large predators, contend wildlife conservationist Hart and anthropologist Sussman.... [T]he authors novel proposals merit serious consideration.Publishers Weekly

In an agile, knowledgeable presentation, the authors contest a popular conception about human evolution: that ancestral hominids were hunters.... To make their case, which eminent paleoanthropologist Ian Tattersall extols in a preface as the first comprehensive synthesis of the information available about predation on humans, Hart and Sussman marshal both fossils and behavioral studies of living primates. The authors prose is wryly irreverent, as if intended to keep a lecture class awake and interested.Booklist

Their thesis is far more complex than merely changing one letter to transform man the hunter into man the hunted. Hunt and Sussman are looking at the whole of human history in a light thats quite different from what most of us have been taught, and... their overall effort is thought-provoking and pretty persuasive.St. Louis Post-Dispatch

[R]eaders will eagerly proceed through chapters about the interaction of primates with felines and canines, reptiles and raptors, even sharks. Those are far from dry scientific presentations. The writing is rich with well-crafted stories drawn from the fossil record and from modern observations of predation on our fellow primatesand humans.

The Dallas Morning News

FOREWORD TO THE FIRST EDITION

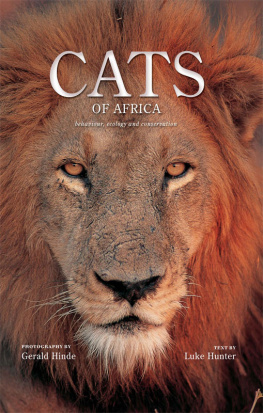

Students of human evolution (like hapless skiers attacked by mountain lions) have always held equivocal views about the place that Homo sapiens and its predecessors have occupied in the food chain. And as a result they have tended to straddle or shuttle between extremes when attempting to reconstruct the behaviors and lifestyles of our earliest ancestors. Two diametrically opposed traditions in the artistic representation of early hominid lifeways run right back to the very beginnings of paleoanthropology in the mid-nineteenth century. Some of the many artists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who specialized in re-creating prehistoric scenes typically depicted small groups of puny and vulnerable early humans huddled nervously around a campfire while big cats circled, awaiting their opportunity to pounce. Others preferred to represent the noble savage, proud and erect and usually armed with a hunting spear or a stone axe (and sometimes with a dog at his heels), striding out in search of quarry. The discovery in 1879 of the astonishing animal images adorning the ceiling of the cave of Altamira, Spain, taken early on to consist of straightforward if powerful and stylized representations of the prey animals of the Ice Age hunters who made them, gave a huge impetus to interpretations of the latter kind. Still, the duality of interpretation lingered well into the last century, possibly because both interpretive schools had in common a tendency to emphasize the importance among humans, then as now, of social cooperation, either as an essential ingredient in defense against predators or as an integral component of successful hunting. Another frequent element in these rather anecdotal scenes displayed the use of intelligence and guile by hominids to compensate for their relative lack of strength and of such inbuilt weapons as dagger-like canine teeth. Understandably for those days when the human fossil record was tiny, ancient and extinct kinds of humans were most commonly viewed somewhat as junior-league versions of ourselves, with at least echoes of our own vulnerabilities and strengths.

Perhaps unexpectedly, when serious scientific attention began to be turned specifically to the matter of how early hominids had lived and thrived within their environments, this attention was focused not on the lifestyles of humans in the late Ice Ages, but rather on the behaviors of truly ancient human precursors. During the second quarter of the twentieth century, Raymond Dart presented the first diminutive hominid bipeds as murderers and flesh hunters, whose violent proclivities had inevitably led to the blood-spattered, slaughter-gutted archives of human history. Based largely on an interpretation of patterns of bone and tooth breakage at ancient australopith (archaic, small-brained hominid biped) sites in South Africa now known to date between about 3 and 1.5 million years ago, Darts vision of humanitys origin in a group of vicious, tool-wielding predators seized the public imagination in mid-century when it was popularized by the scenarist Robert Ardrey in his beautifully crafted book African Genesis. Significantly for the recent history of the human sciences, this dramatic view of Man the Hunter influentially held the stage during the period when many of todays senior figures in paleoanthropology and primatology were being trained.

Inevitably, though, the Dart/Ardrey view of mankinds bloody birth ultimately produced a reaction that swung interpretation toward the opposite end of the spectrum of possibilities. Studies by Bob Brain during the 1960s and 1970s of South African australopith assemblages clarified how the fossils came to be jumbled and fragmented as elements washed into underground cavities, or as body parts accumulated by predators or scavengers, rather than as a result of murderous breakage by hominid killers in their lairs. Dramatically, Brain demonstrated that twin punctures in a skull fragment of a juvenile australopith were perfectly matched by those of a fossil leopard, whose relative had doubtless dragged the hapless hominids body into a tree, as leopards still do with the corpses of impalas and other unfortunate prey.

Still, some of the South African australopith sites, notably that of Sterkfontein, cover a period of well over a million years. And in his detailed examination of this site in his 1981 book The Hunters or the Hunted? Brain suggested that while at about 2.5 million years ago the cats apparently controlled the Sterkfontein cave, dragging their australopithecine victims into its darkest recesses, by a million years later hominids had not only evicted the predators but had taken up residence in the very chamber where their ancestors had been eaten. This set the stage for a more nuanced view than Darts of early hominid lifestyles, and one which emphasized the vulnerability of the small-bodied early hominids who first quit the shelter of the forest and ventured out into the expanding woodlands and grasslands. Still, Brains book envisaged an almost inexorable progression by hominids toward predatory behaviors.