For my mother, who has the same handwriting as Santa Claus

Pyrex Christmas Party Mug, Corning Glass Works, Charleroi, 1963. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York

CONTENTS

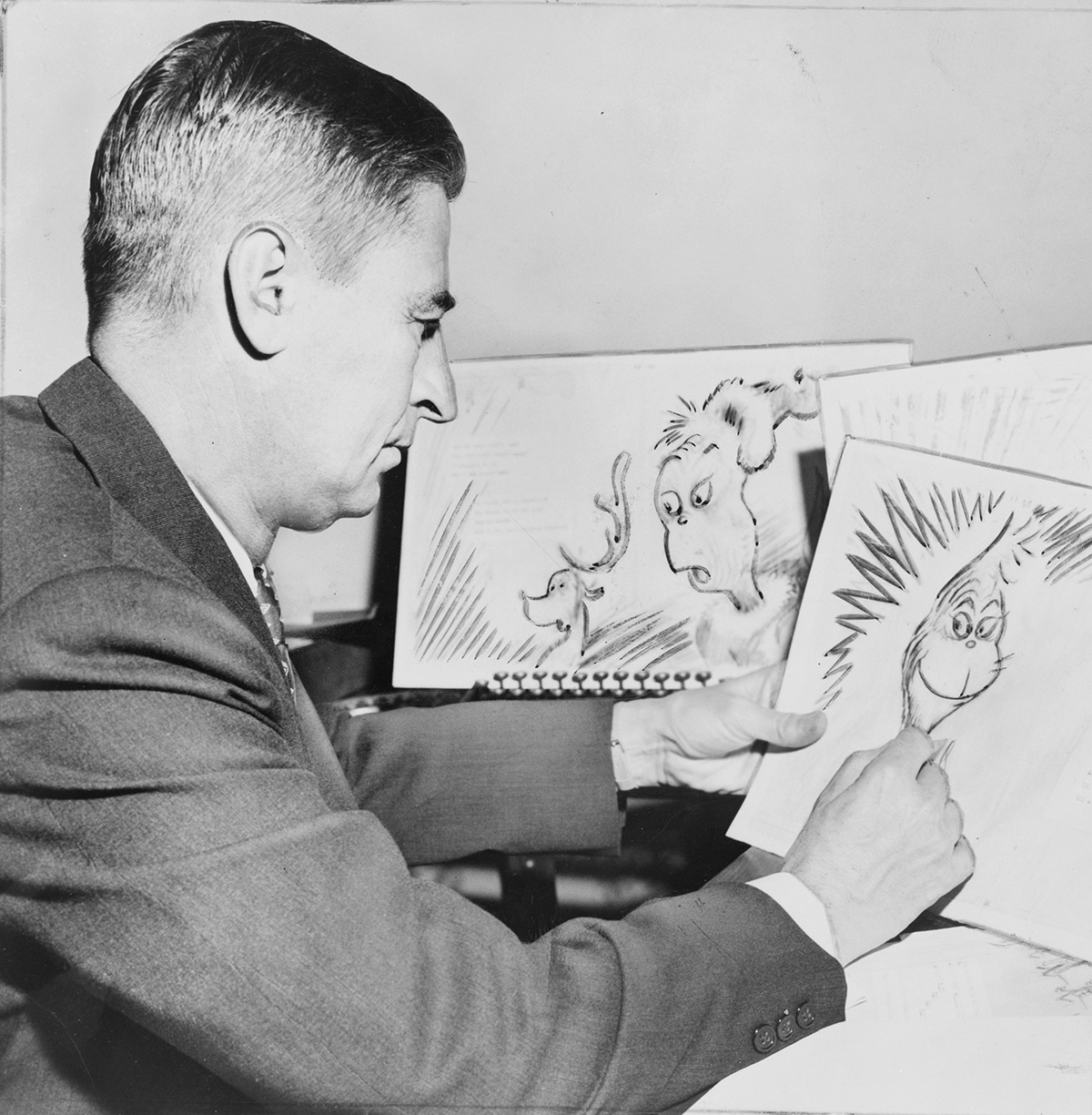

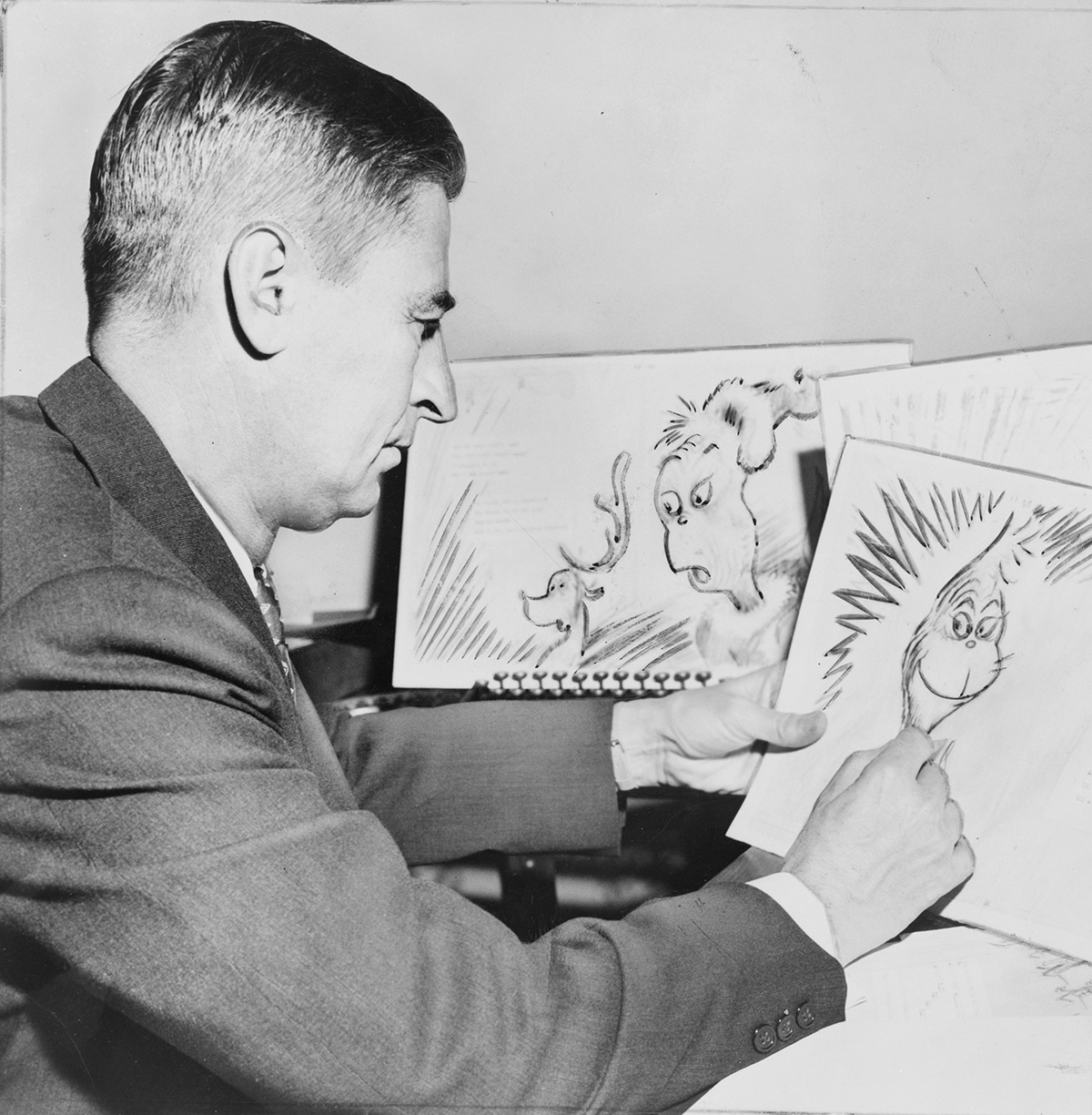

Theodore Geisel, American writer and cartoonist, at work on How the Grinch Stole Christmas, 1957. Photo by Al Ravenna, World Telegram and Sun. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Christmas trees and wreaths in store window display, 1941-42. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Alaskan reindeer pull Santas sled during the Pageant of Peace, Washington, DC, 1957. Photo by Volkmar K. Wentzel/National Geographic/Getty Images.

Christmas has a way of making us wistful for the past. Even when I was a kid, longing for an orange-and-black Garfield telephone during the gadget-obsessed 1980s, Santa Claus himself was pretty low tech. He may have brought us newfangled toys, but his accou-terments never seemed to change: the sleigh, the red suit, and the handwritten thank-you notes left near the tableau of cookies and carrots wed put out for him and his eight reindeer on December 24.

My memories are steeped in old-fashioned details: decorating our trees with vintage ornaments from different generations of my family (mercury glass from my grandparents, hand-stitched felt from my parents) and arranging our terra-cotta santons just so. Modeled on Provenal villagers, these figurines celebrate the baby Jesus in typically French fashion: by bringing wine, fresh baguettes, and other things to eat and drink. There were lots of contemporary touches, like plastic tinsel and certain beloved holiday specials like A Charlie Brown Christmas, but overall, the experience was almost like time travel back to a period in which people baked, sang, and generally made their own fun with a minimum of technology.

Thats why I was intrigued a few years ago when I stumbled upon an article about Soviet-era New Years cards that depicted Santa Clauss Cold War counterpart, Grandfather Frost, riding rocket ships and delivering presents from low orbit.

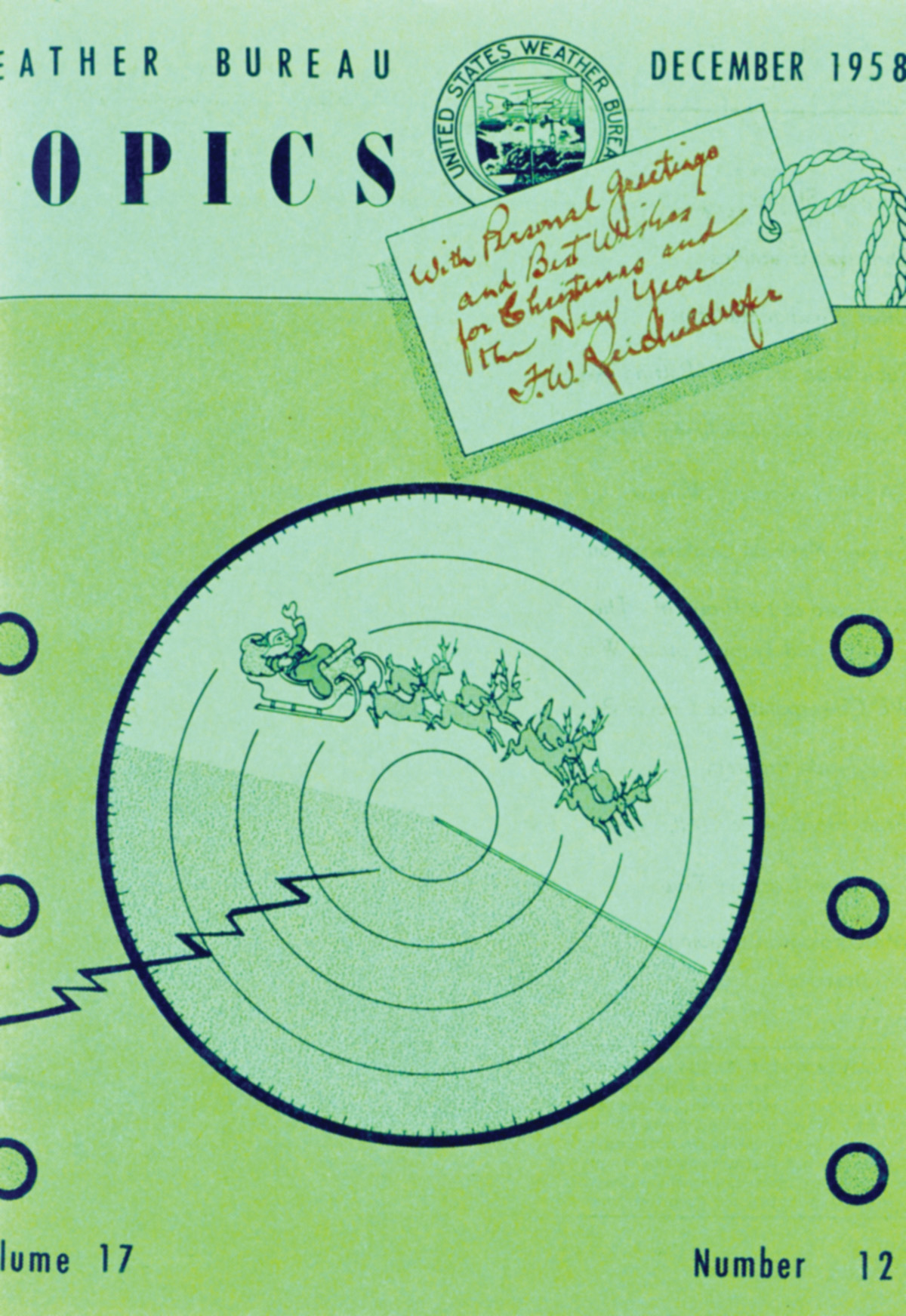

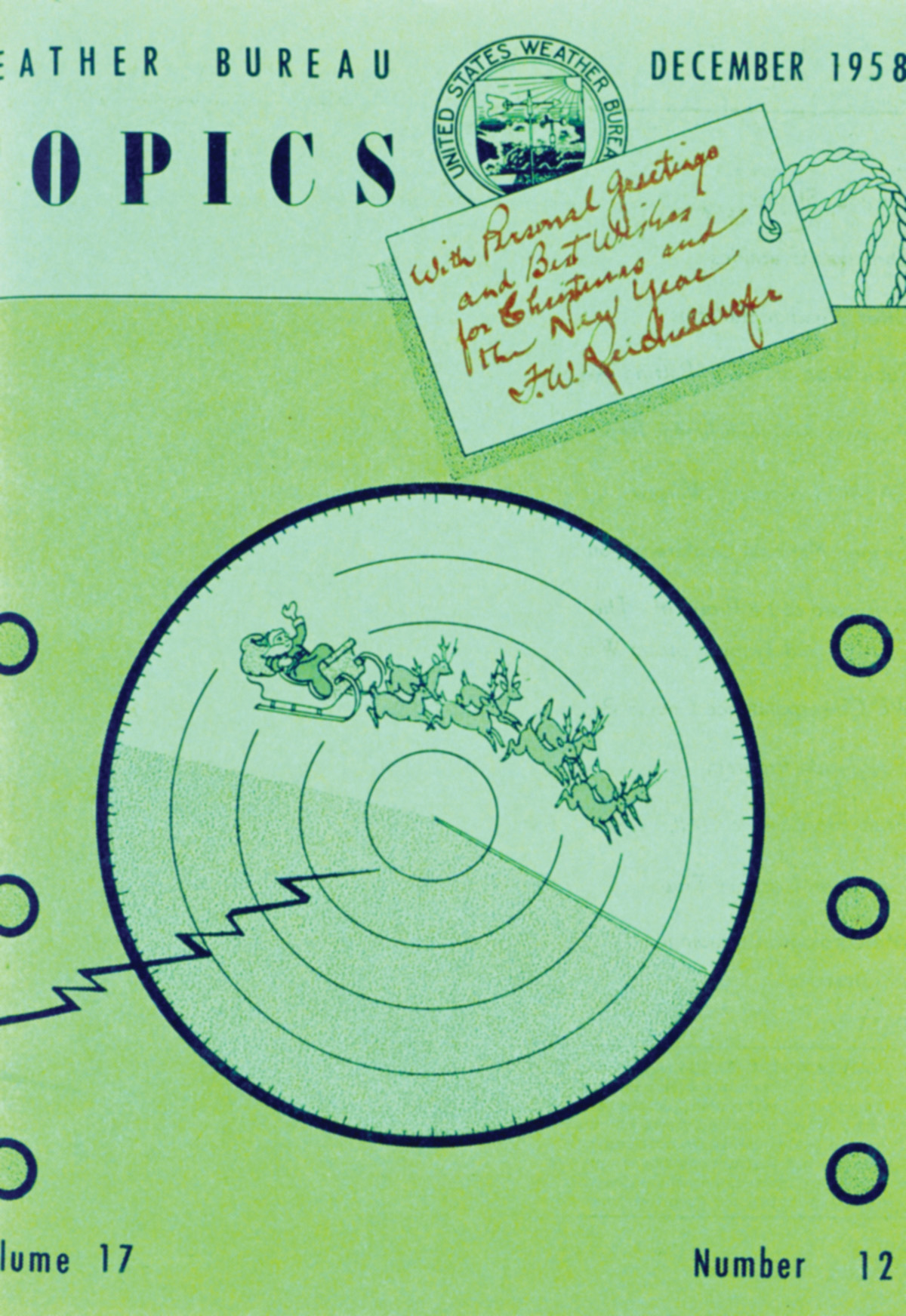

With a little digging, I started to discover that our own Santa Claus had dabbled in space travel, too. There are traces of it evident today: NORAD still tracks Santa on radar, as it has since 1955.

Cover, Weather Bureau Topics, December 1958.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Central Library.

The period from 1945 to 1970 took Christmas in America (and, indeed, New Years celebrations in the USSR) on a sharp detour away from the Victorian charm of the Christmases that so many of us remember, even those of us who grew up at the end of the Cold War or right after it. Its a funny exercise in futuristic nostalgia, like observing how the set and props of the original Star Trek series anticipate our present-day technologies, even as it all looks very dated. Fueled by a sense of optimism and widespread prosperity postwar Americans embraced a high-tech version of a holiday that had long been steeped in ancient lore and symbols of an old-fashioned way of life: sleighs, candles, handmade toys, and the worship of trees.

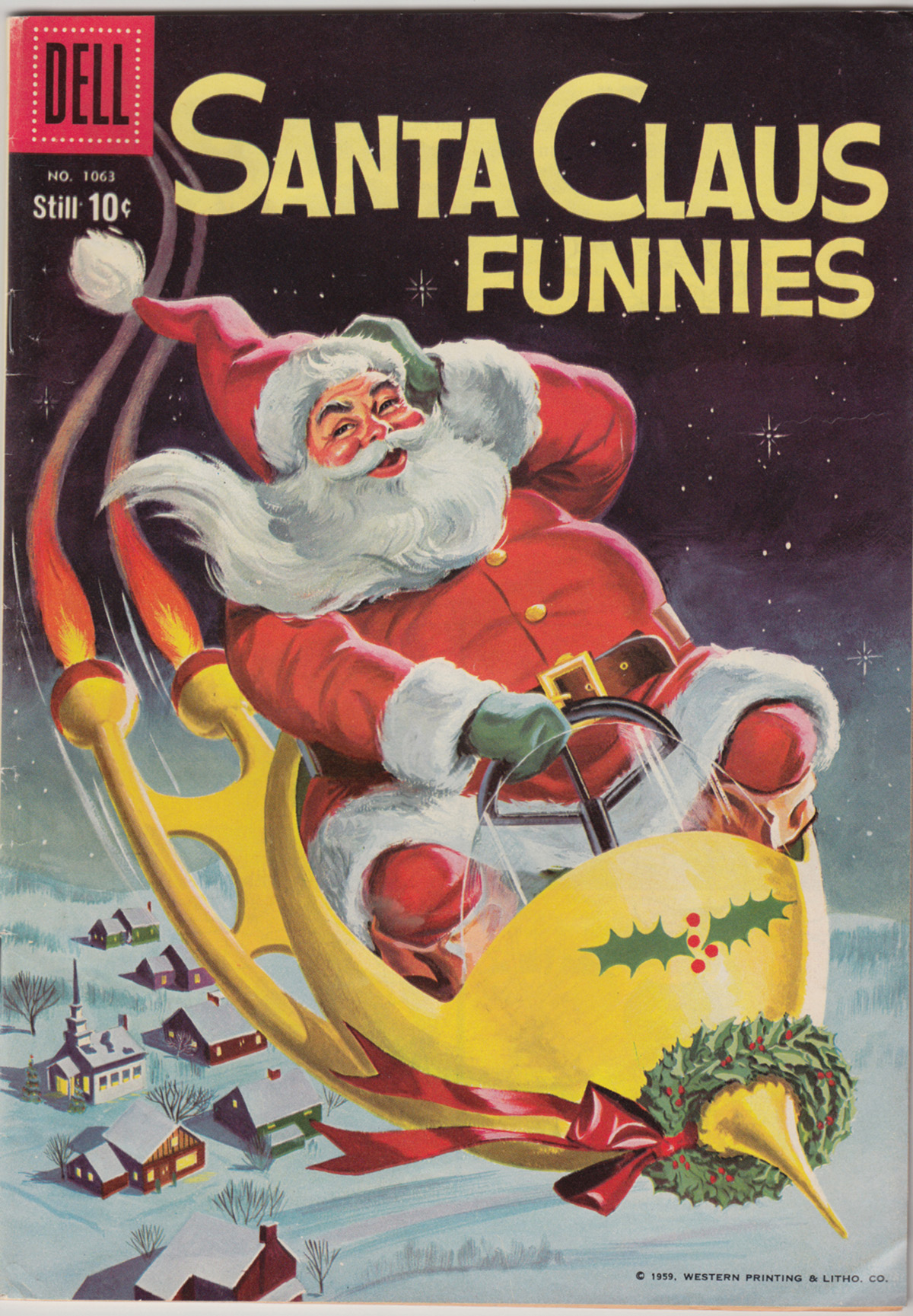

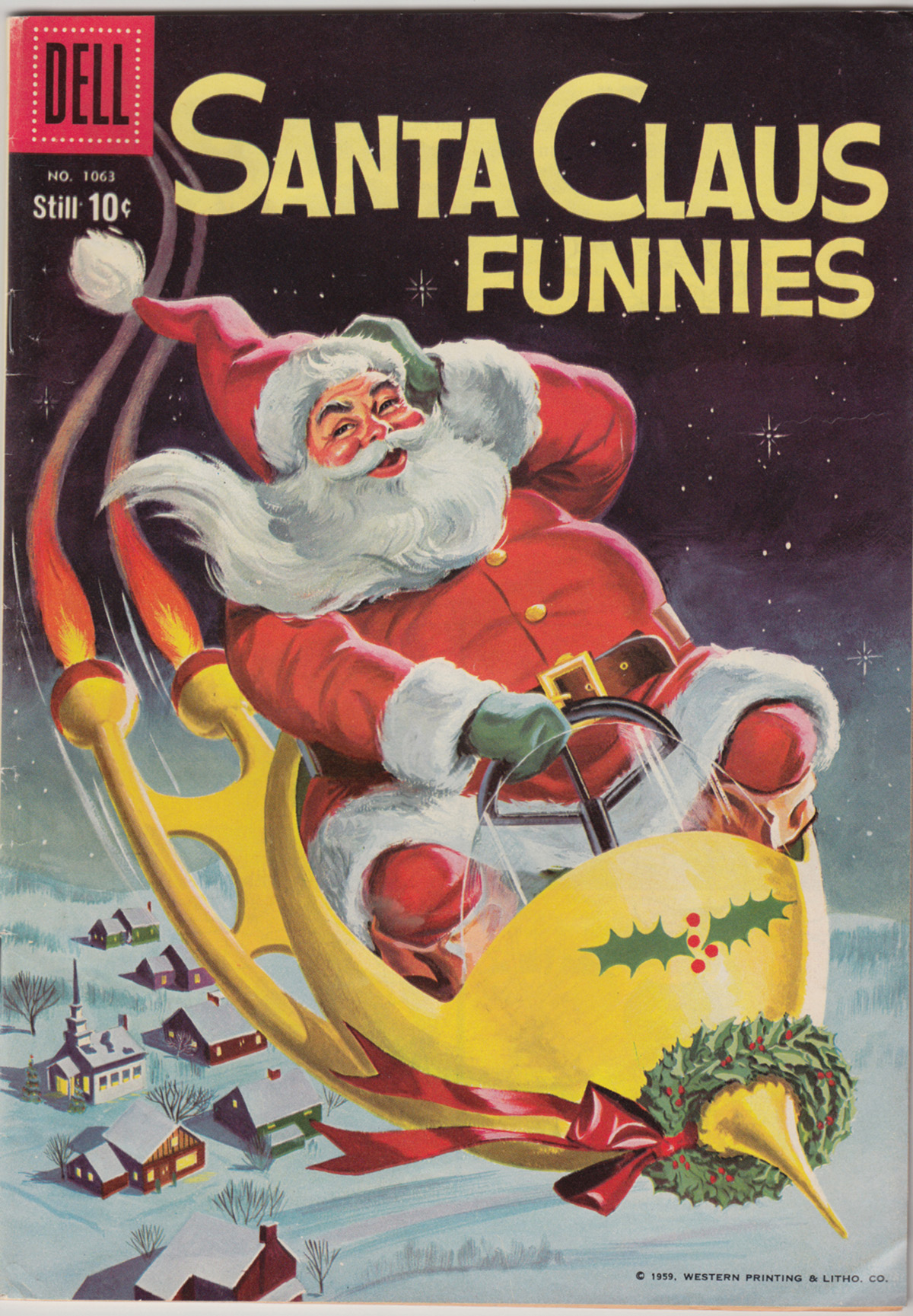

Cover of the Dell Santa Claus Funnies, December 1959, Western Printing & Litho Company.

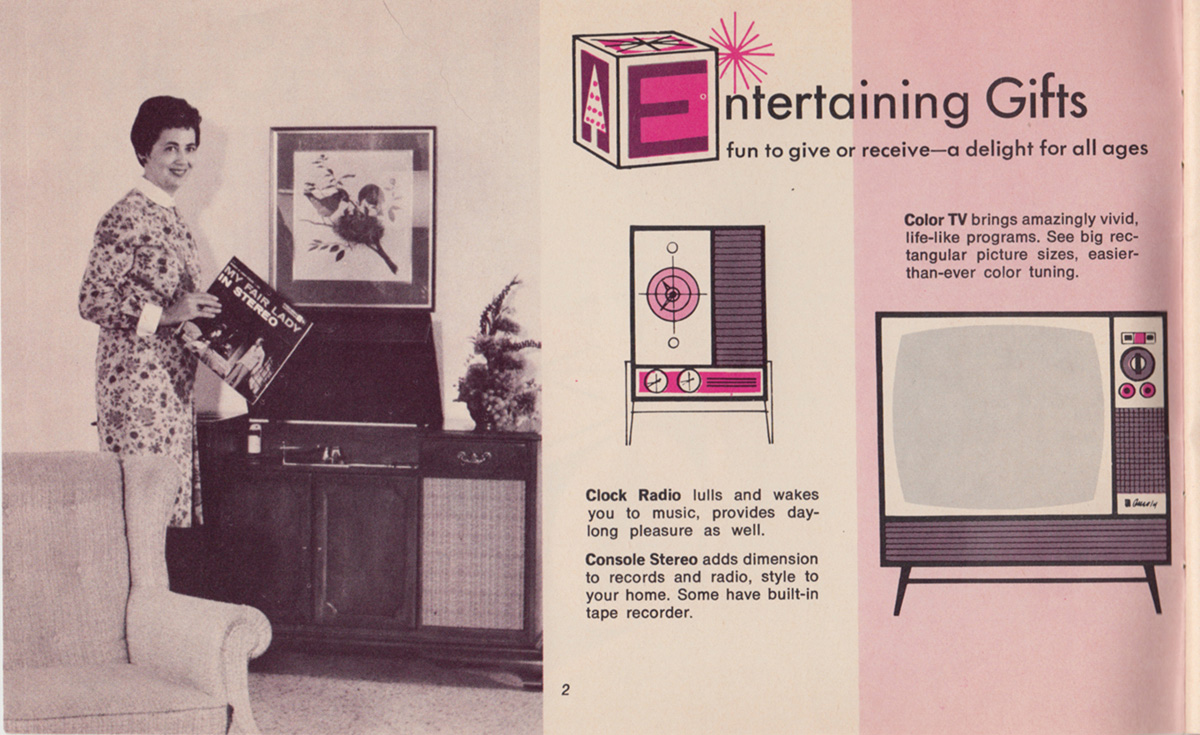

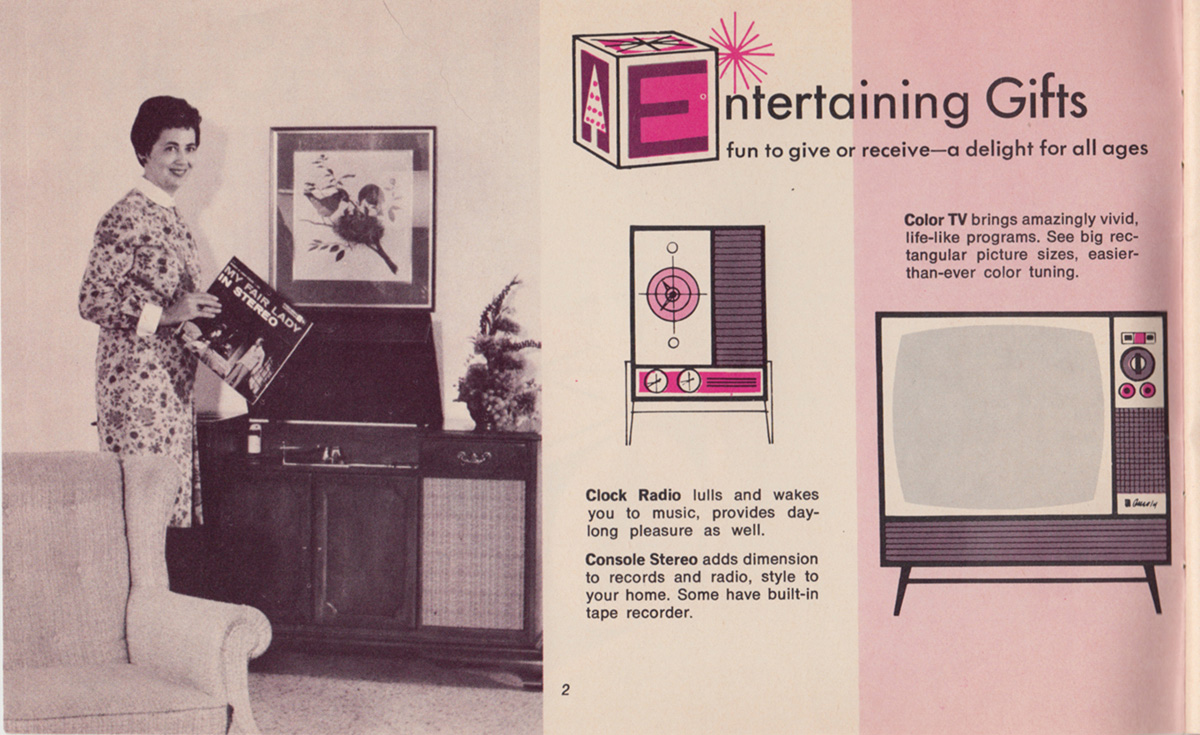

Treasury of Christmas Ideas, Western Light and Telephone Company Home Services Department, 1960s. Lincoln Electric System.

In the mid-1960s, a crackling Yule log glowed from Zenith television sets, and Christmas trees fashioned from shiny aluminum sparkled in the winter light. There are lots of reasons for this, but taken together, the enthusiasm for new materials, science, space travel, bold graphics, and a special love of convenience foods paint a picture of a society that was exhilarated by the possibilities of its new superpower status and a bit tentative, even frightened, of the postwar world it now occupied. The material culture and popular entertainment of the era put a brave face on it all, but the mysteries of space exploration, atomic energy, and the prospect of armed conflicts with the Soviet Union were very frightening to contemplate. This curious mixture of economic security and global anxiety made Americans want to nest like never before; the most extreme iteration of this impulse was the iconic home bomb shelter stocked with board games and canned goods.

In every era, the celebration of Christmas elicits a sense of wonder and childlike glee in adults and children alike. Each holiday season, the Christmas story reminds us that our own families and circles of friends are their own sorts of miracles to be celebrated. We cultivate a sense of magic around the holiday to remind ourselves of our good fortune, or to make manifest our hopes for better times to come. In the postwar era, a space-faring Santa, ultra-mod Christmas cards, wrapping paper, aluminum trees, and an array of scientific and domestically inspired toys gave tentatively optimistic Americans a way to make the Space Age their own, even familiar and cozy; something to behold in awe, not something to fear.

In 1957, Theodor Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, introduced American readers to their very own Atomic Age Scrooge: the Grinch, a sinister green critter who hated Christmas so much he vowed to steal it from the cheery citizens of Whoville, as though Christmas itself were a commodity for sale at a department store.

Geisels beloved holiday tale, which has since been adapted for television, film, and Broadway, was intended as a good-natured but serious critique of postwar Americas love affair with all the commercial trappings of the holiday season. The inspiring moral of How the Grinch Stole Christmas! is that Christmas isnt a thing to be stolen at all, but a celebration of family and good cheer that arrives on cue every December, presents or no presents.

Charles Dickenss 1843 holiday masterpiece, A Christmas Carol, gave us the classic Christmas antihero, Ebenezer Scrooge: a cruel taskmaster, ungenerous toward his sympathetic employee, Bob Cratchit, and his family. When Scrooge sees the light on Christmas morning after hes visited by the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future, he responds by sharing his material abundance with strangers and colleagues alike: gifts for the Cratchit children, a Christmas turkey, and a long-overdue raise for Bob. Its a happy ending that made perfect sense in Dickenss time, when things like unregulated child labor and urban poverty were pressing issues in Great Britain. Scrooges Christmas enlightenment underscores the idea-relatively new at the time-that material prosperity should be shared by everyone.

Next page