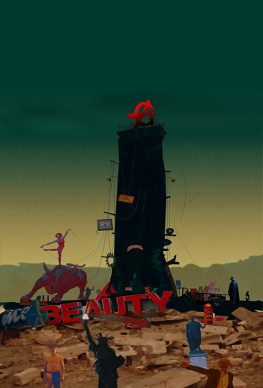

The Ballerina and the Bull

The Ballerina and the Bull

Anarchist Utopias in

the Age of Finance

Johanna Isaacson

Contents

The hacienda must be built:

DiY in the City

All citations are in MLA format. Page numbers appear in parentheses. Authors names are either in text or in parentheses.

Introduction

No Future

From the uprisings in Seattle in 1999 to the Occupy movement of 2011, our moment has seen a resurgence of an anarchist sensibility. Against the vacuity and drift of financialized capitalism, these insurgent movements have insisted that an alternative is possible. But the idea of possibility itself, and the ability to maintain a stable boundary between utopia and dystopia, shifts in an age of historical breakdown. As Fredric Jameson has recently argued, the power of the negative is intensified in our new moment of historical crisis an ominous perpetual present in which no one knows whats coming and indeed no one knows whether anything is coming at all (On the Power). This book makes a wager for jerry-rigged, DiY practices, social experiments, quixotic contestations against the capitalist behemoth that allow us to see the limits and hopes of our largely depoliticized moment. DiY offers an alternative to a narrative that says we have arrived at the end of history and that there is no alternative to the isolation and alienation of capitalist individualism. The title of this book, The Ballerina and the Bull, refers to the initial call for Occupy Wall Street in the pages of anti-corporate Adbusters magazine, which featured an image of a simply dressed ballerina perched on the symbol of Wall Street, a rearing bull. While Adbusters framed this as a kind of triumph of the ballerina over the bull, I take the dynamism of this duality as an emblem of the generative relationship between the prefigurative, utopian actions of anarchists as they come up against economic and social limits to transformation. This tension itself is a rich point of entry into political-cultural dilemmas and potentialities of our spectacular moment.

Periodizing the Present

With some reluctance, I am calling contemporary DiY postmodern, which, with Fredric Jameson, I see as interchangeable with late capitalism. Other interpretations of postmodernism see it as a post-Marxist moment. However, I follow Ernest Mandels periodization of late capitalism which suggests that capitalism has mutated and adapted to crises, rather than waned, becoming if anything, a purer stage of capitalism than any of the moments that preceded it (Jameson, Postmodernism 1). In this stage of late capitalism, the appearance of endless choice and endless identity positions creates the need for intensified scrutiny, modes of thinking that aim not at providing answers but at figuring out the questions to ask. Contemporary anarchism correlates to post-Sixties logic, as Jameson frames it, in which the unbound energies which gave the sixties their energy were harnessed to a new stage of global capitalism, giving way to an expansion of proletarianization and its resistance (Periodizing the Sixties 108-109). Looking at these struggles as both theory and practice offers us a point of purchase from anti-utopian, neoliberal capitalist realism.

This navigation of contemporary byzantine forms of reality requires the category of mediation and an epistemology that is able to move beyond surface phenomena. Although the category of the proletariat may seem outdated in a moment of widespread first world deindustrialization, I want to argue that a messily grouped emergent precariat, a word which Im using, following Aaron Benanov, as a placeholder for a multi-levelled and differentiated workforce that is nevertheless affected deeply and systematically by precarity, has the potential to occupy this standpoint from which mediation is accessible. The precariat can be seen as the majority of the globes occupants: those who lack a social contract with the welfare state, lack trust relations with capital, lack labor security, lack reliable and consistent status positions and attachments (Standing 10). This precariat has a special place in relation to knowledge, a standpoint from which it can embody both the position of a subject and an object. The standpoint of the precariat allows some purchase on immediacy and facticity by refusing to let facts stand for themselves, and instead interrogating the values of the society in which those facts exist. At stake in the concept of precariat epistemology against the empirical standpoint of power is an understanding that social relations arent only as they appear and are vulnerable to change.

The anti-utopian periodizations that frame the present as the end of history devolve from this empirical logic which accepts the facticity of power relations and cultural values unquestioningly. What Mark Fisher calls capitalist realism demands that we accept the present as eternal. The standpoint of the precariat keeps open the idea that static, fetishized forms of history and commodified life contain clues to the relationships which make social realization impossible under capitalism, and that the knowledge of these relationships is an essential element in transformation and realizing the possible. As zinester Johnny Sunset notes, By the very definition of who and where we are, we are made to imagine the possibility of a lawless world (7).

In this moment, subsumed by globalized capital, representation and aesthetics play a key role in providing what Alberto Toscano and Jeff Kinkle call cartographies of the absolute. This representational mapping, however, takes the form of negation, the gauging of that which is by definition invisible. This book looks at the way that DiY maps these disappeared and marginalized spaces and logics. I argue that anarchist utopian projects can be read simultaneously for their prefigurative and cognitive aspects. In both of these registers there is a shift from the emphasis on the proletariat and its context of the factory to the post-industrial precariat and its urban milieu. Here, the problem of representation is diagnosed in postmodern city-dwellers inability to map their own sense of place.

Implied in this dual view of anarchist utopia is also a critique of anarchist self-perception. Recognizing the limits and horizons of direct action does not constitute pessimism or cynicism. In fact, it does the opposite. A self-critical view of anarchist utopia along with a foregrounding of political economy allows for a true optimism that structural change is possible. This optimism in what I am calling DiYs expressive negation counters the pessimistic narrative of the end of history in which the perpetuity of capital is naturalized and seen as inevitable. This form of complacent realism finds its rhetorical center in a discourse of maturity set against an irresponsible youth culture. While there is nothing inherently revolutionary about the category of youth, and indeed, this figure can be seen to have analogous characteristics to a hedonistic stage of commodity capitalism in which consumerism and culture eclipse the serious business of building new social relations, a simplistic critique of youth and political passion will not suffice in an age of enforced austerity. The rise of austerity as an antagonist should teach us that maturity is a central ideologeme of the right used to coerce the global precariat to participate in her own oppression. The postmodern foreclosure of the concept of utopia and the narrative that foregrounds the end of grand narratives came at the price of an attenuation in the scope of political and historical vision. We should instead analyze youth culture generously with the goal of resurrecting and broadening struggle, following Marxs thesis on Feuerbach: Philosophers have hitherto only

Next page