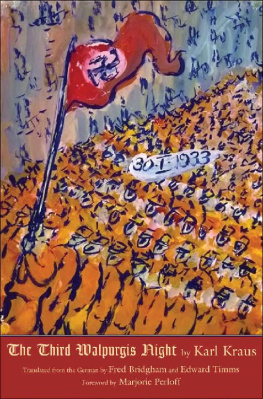

The Third Walpurgis Night

I am still compared favorably with Goebbelsnot a pleasant experience.

The Third Walpurgis Night

The Complete Text

KARL KRAUS

TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN BY

FRED BRIDGHAM AND EDWARD TIMMS

FOREWORD BY MARJORIE PERLOFF

The Margellos World Republic of Letters is dedicated to making literary works from around the globe available in English through translation. It brings to the English-speaking world the work of leading poets, novelists, essayists, philosophers, and playwrights from Europe, Latin America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East to stimulate international discourse and creative exchange.

English translation copyright 2020 by Fred Bridgham and Edward Timms. Preface copyright 2020 by Yale University. The English translation is based on the 1952 edition of Die Dritte Walpurgisnacht, published in German by Ksel in Munich.

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Set in Electra and Nobel type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

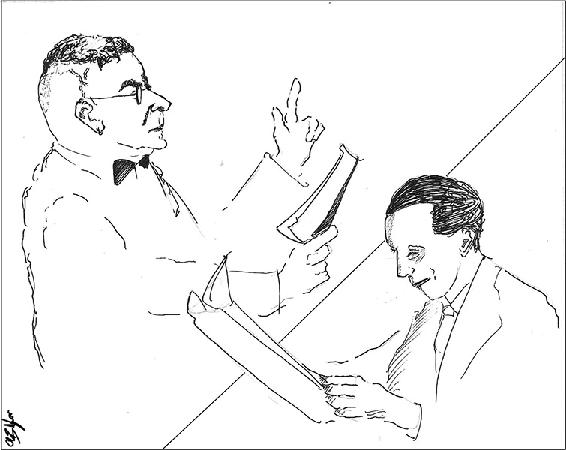

Frontispiece: Printed with permission by Otto Bridgham.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019952815

ISBN 978-0-300-23600-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

This, the first translation of the great political satire Karl Kraus produced in his final years, is a critical bombshell, a book that patiently and devastatingly documents the role of the medianewspapers, journals, radio broadcasts, speeches, pamphlets, even poemsin solidifying Hitlers control of Germany in the early months following his election to the chancellorship on January 30, 1933. Far from providing any sort of resistance, the German media almost immediately started providing cover and propaganda for the Nazi regime and did so with great cleverness and surprising literary skill. What we now call fake news (Falschmeldung) was the order of the daya frightening mlange of half-truths and distortions that played on the consciousness of ordinary citizens, convincing them that the new regime was doing the right thing. In the Age of Trump, Krauss book could hardly be more timely, although, as I shall suggest below, the differences between our time and the Nazi interregnum are also remarkable.

As the editor-translators tell us in their introduction, Die Dritte Walpurgisnacht was composed and typeset between May and September 1933, but Kraus put it aside, worrying that its publication might provoke terrible reprisals against the Jews of Germany (and, by extension, Austria). Kraus never witnessed the Anschlusshe died in 1936and then the war intervened: Die Dritte Walpurgisnacht was not published until 1952. Translation has proved to be a major challenge because the book contains so many local and arcane references to persons and places as well as many literary allusions: it presupposes a certain familiarity with everyday life in the Germany and Europe of the early 1930s as well as with Goethe and other German writers. But, as Edward Timms, until his death the leading Kraus scholar in English, and his expert collaborator Fred Bridgham have understood, once we grant Kraus his particular donnethat creative citation from documentary material can tell us more about a particular moment than can any objective historical accountKrauss essay becomes surprisingly accessible, especially for a contemporary audience accustomed to conceptual writing and art. Together with Krauss great documentary drama TheLast Days of Mankind, which Bridgham and Timms translated and published in 2015, The Third Walpurgis Night introduces us to a Karl Kraus who was much more than the author/editor of the wicked journal Die Fackel or the coiner of clever political aphorisms, as he is primarily known in the anglophone world. This Karl Kraus is a great Swiftian satirist.

The technique of The Third Walpurgis Night is almost entirely one of appropriation: Kraus gives us over a thousand excerpts from the political discourse of the first six months of 1933, interspersing hundreds of literary allusions, many of them from Goethe, but also dozens from Shakespeare, and other lyric and dramatic works. Even when we dont recognise the source of this or that citation, the impact of Krauss satire is extraordinary, and the contemporary reader will experience a shock of recognition on page after page.

Walpurgisnacht: the first recording of the word was by Johannes Praetorius in 1668, referring to the Christian feast day of the eighth-century abbess St. Walpurga, a feast traditionally celebrated with bonfires and fireworks on the eve of May Day (April 30), to ward off witches and demons. Kraus is of course referring primarily to the famous Walpurgisnacht scenes in Faust 1 and 2, but Goethes treatment of the demonic has none of Krauss ferocious political animus: Kraus once remarked that a second Walpurgis night was World War I, whose catastrophic outcome he predicted immediately in 1914 and satirized mercilessly in The Last Days of Mankind (1922).

The third Walpurgis night, in any case, is a scene of writingthe writing on the toilet wall, as Kraus put it, initiated immediately upon Hitlers assumption of power. The books famous opening sentence, Mir fllt zu Hitler nichts ein, is meant quite literally: Krauss focus is not on Hitlers Mein Kampf or on the Fhrers own speechesthat would be too easybut on what appeared, day by day, in print, on the radio, and in public forums. From reports in provincial German newspapers, to the seemingly liberal Austrian Neue Freie Presse, to the commentary of Hitlers famed Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels as well as the rhetoric of respected thinkers like Martin Heidegger and Gottfried Benn, the Nazi ethosand especially its virulent hatred for the Jewswas relentlessly and carefully promoted.

The case of Goebbels is especially interesting. In American war movies of the 1940s Goebbels and Goering (Hitlers deputy) were usually represented as sinister versions of Laurel and Hardy or Abbott and Costello. But Goebbels was no clown. The top student in his high school class and the holder of a Heidelberg doctorate in Romantic literature, Goebbels was a failed littrateur turned bank clerk, who had joined the Nazi Party as early as 1924. Well educated and just clever enough to be extremely dangerous, he paid lip service to avant-garde notions of Making It New, assuring his readers that Things are on the move. Radio, Goebbels is quoted as declaring, should never only play the ideological card, nor should art always beat the big drum. Appealing to educated readers, he vigorously denounced kitsch: no more electoral slogans on everyday crockery or the misuse of the Nazi symbol on every sheet of rolls of paper in places where the walls are already covered with the same symbol. The campaign against kitsch is then twisted to justify the call to arms against the un-German spirit, although in fact that campaign could hardly have been kitschier as when, for the Reich Chancellors first visit to Berlins City Hall, on both sides of the vestibule heralds in historical dress were to be lined up.

Next page