Karl Kraus

The Last Days of Mankind

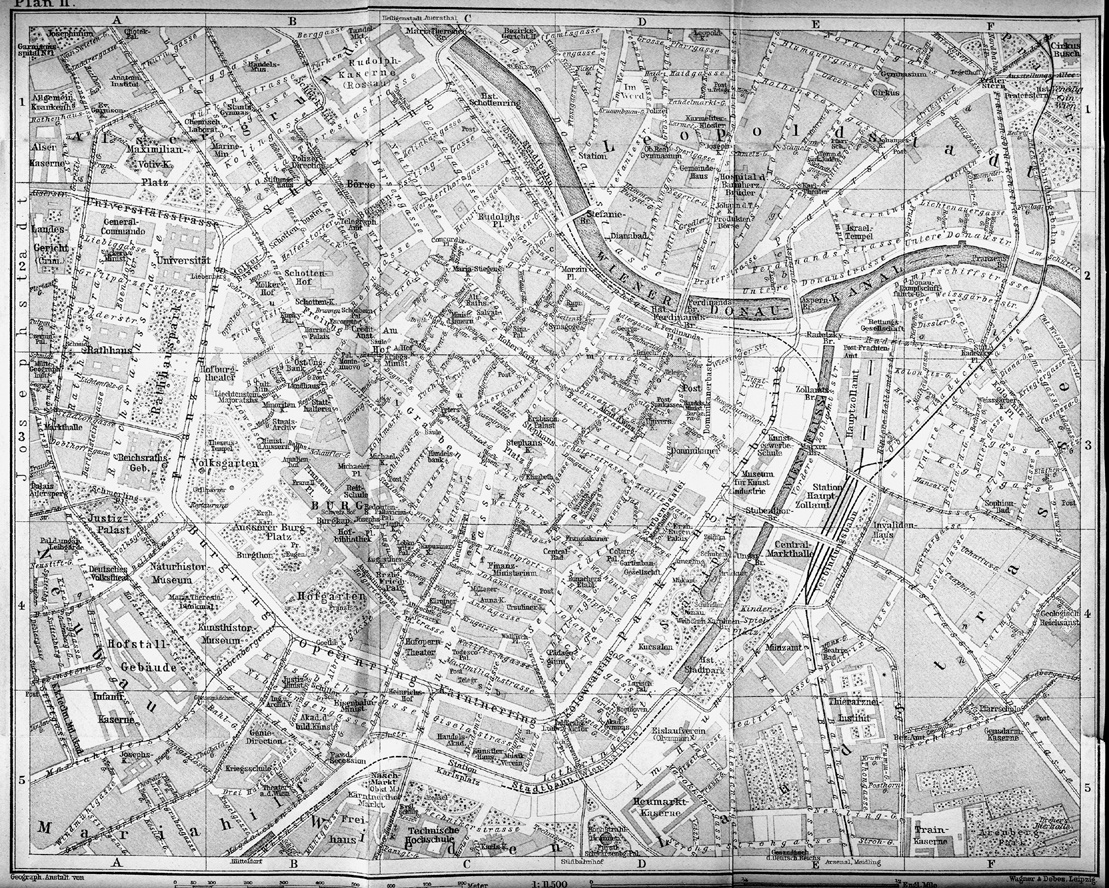

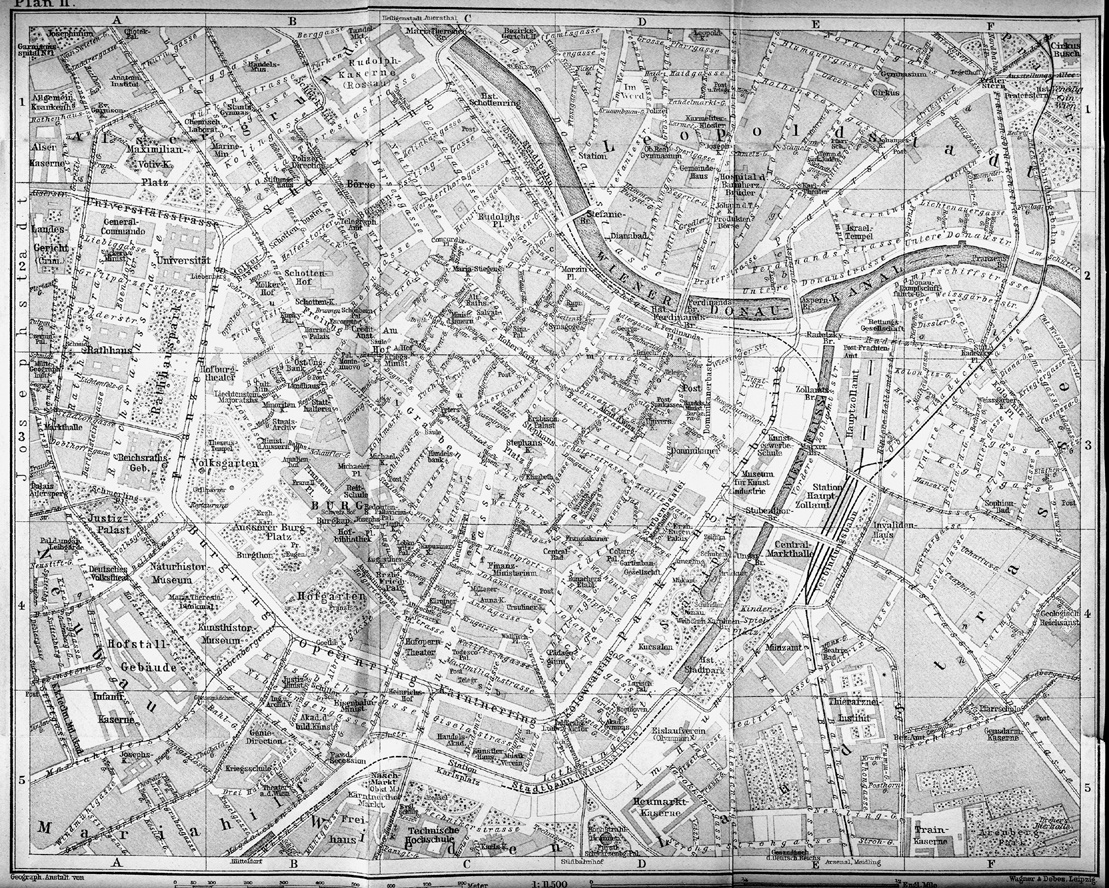

Plan of Vienna City Centre, 1905

INTRODUCTION: FALSEHOOD IN WARTIME

Edward Timms and Fred Bridgham

The early twentieth century was the great age of the newspaper press, as mass literacy endowed the printed word with unprecedented power. Newspaper production was revolutionized by rotary presses and linotype compositing machines, while modern roads and railways, together with the telephone, telegraph, and teleprinter, were transforming communications. In Western Europe and North America democratic institutions, social reforms, and scientific discoveries seemed to be laying the foundations for a new era in the history of mankind. But it was also a period of intense imperial rivalries, backed by highly trained forces and sophisticated armaments industries. Given the precarious international situation, it was possible at moments of crisis for journalists to tip the balance between peace and war. Liberal papers such as the Manchester Guardian (edited by C. P. Scott) and the New York Times (under Adolph Ochs) may have been committed to the peaceful resolution of conflicts, but wars were good for newspaper sales. Moreover, wealthy proprietors like Hearst and Northcliffe, Hugenberg and Benedikt, were imperialists capable of pressurizing governments into declarations of war.

Almost alone in the period before the First World War, the Viennese satirist Karl Kraus saw the press as an apocalyptic threat. In his magazine Die Fackel (The Torch), founded in April 1899, he would reprint prize examples of newspaper propaganda and expose their falsification of reality.1 His witty diatribes attracted a large readership, and with a print run of over 10,000 copies the magazine proved viable without having to rely on commercial advertising. To protect his independence Kraus created his own imprint, Verlag Die Fackel, which published book editions of his writings.

Where the editorials of the leading Austrian daily, the Neue Freie Presse, were celebrating the advances of German culture and the triumphs of European civilization, Kraus would expose the realities of conflict and suffering. He had a gift for dissecting the clich-ridden language of his contemporaries. Sonorous metaphors like standing shoulder to shoulder evolved into satirical leitmotifs, culminating in his indictment of the anachronistic ideals that sustained the Central Powers during the First World War. His own style, by contrast, was enlivened by an aphoristic wit and moral fervour that left his readers uncertain whether to laugh or cry.

The apocalyptic tone of Krauss bleakest visions appeared to leave little hope for mankind. Borrowing from the Bible in a prophetic essay entitled Apocalypse, published in October 1908, he identified Kaiser Wilhelm II as an apocalyptic horseman with the power to destroy the peace of the earth.2 Moreover, the dangers arising from autocratic power were intensified by a technology that was running out of control: ultimately, mankind lies dead beside the machines it has created, incapable of putting them to constructive use because so much intelligence has been expended on inventing them (F 26162, 15). This foreshadows the critique of mechanized warfare in Die Fackel of 191418, but it would be wrong to see Krauss satire as exclusively negative. It drew on a conception of human dignity shaped by the moral vision of Kant and the cultural ideals of Goethe. The satire of Die Fackel, which Kraus wrote single-handed from 1912 onwards, combined analyses of impending disaster with the advocacy of a better world.

Kraus was born on 28 April 1874 as the son of a prosperous Jewish paper manufacturer. Growing up in Vienna, he had to contend with the pressures of a deeply conservative and stridently anti-Semitic environment. A recent study by Paul Reitter has identified undertones of Jewish self-hatred in Krauss anti-journalism.3 His writings are certainly shaped by the impulse to construct an identity free of allegedly negative Jewish characteristics, but this is by no means the whole story. A further apparent constraint arises from the fact that Krauss satire is basically a collage of quotations, framed by his own ironic commentaries. This means that much of Die Fackel consists of reports clipped and reprinted from the newspapers of his day. This quotation technique gives his writings their historical density, but it would be wrong to see them as parochial. His satire certainly emerged from a specifically Austrian Jewish milieu, but like the work of Freud and Herzl, Mahler and Wittgenstein it has far-reaching implications.

How Is the World Governed and Made to Fight Wars?

During the years 190814 Krauss critique of the press acquired a new urgency as he highlighted the threat of war. The Austrian annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina precipitated a crisis in the Balkans, provoking a fierce reaction in the Serbian capital, Belgrade. By March 1909 the Austro-Hungarian army was poised to invade Serbia, hoping by this means to crush the political aspirations of the South Slavs within the borders of the Habsburg Empire. However, the government needed to find a moral justification for war and thus to ensure that the conflict remained localized. The Austrian Foreign Ministry accordingly orchestrated an anti-Serbian campaign, finding a willing ally in the patriotic historian Heinrich Friedjung. On 25 March 1909 the Neue Freie Presse published an article by Friedjung which purported to justify military action. Drawing on documents supplied to him by the Foreign Ministry, he accused members of the Croatian Diet (the administration of one of the Hapsburg provinces) of a treasonable conspiracy with the government in Belgrade.

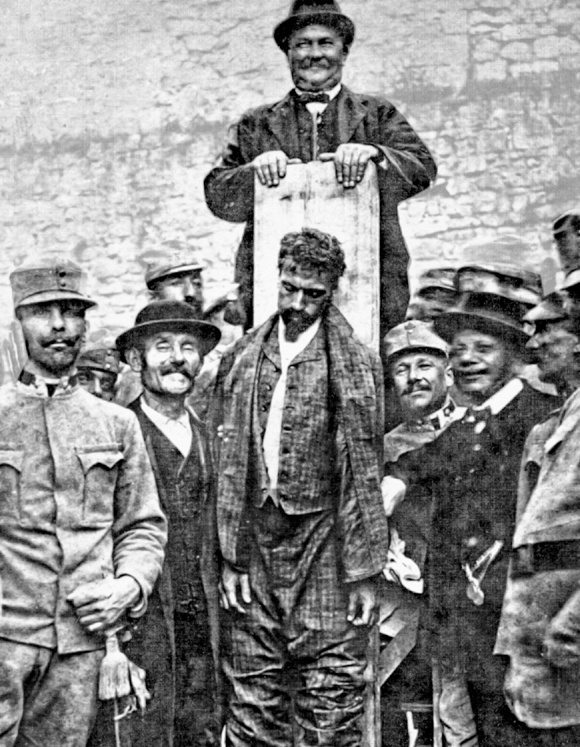

This article was intended as a fanfare for war, but at the last moment, under pressure from Russia, the government of Serbia backed down. The threat of war receded, and in place of the intended humiliation of Serbia it was Austrian foreign policy that was put on trial. Members of the Croatian Diet brought a libel action against Friedjung, which Kraus regarded as so important that he attended in person. The trial, which lasted fourteen days, was fulsomely reported in the Neue Freie Presse. It began with patriotic bluster as Friedjung produced copies of his documents, which identified the alleged conspirators by name. One of those named, Bozo Markovitch, a university professor in Belgrade, was surprised to discover from reports of the trial that he had held secret meetings with the Croatian conspirators and induced them to accept treasonable payments. Risking arrest, Markovitch travelled to Vienna to testify that at the time of the alleged meetings in Belgrade he had actually been in Berlin, attending lectures on jurisprudence. This testimony was greeted by judge and jury with incredulity until the Prussian police, famous for their meticulous record keeping, confirmed that Markovitch had indeed been in Berlin at the time of the alleged conspiracy. The documents were exposed as forgeries and Friedjung was humiliated.

Kraus responded with a trenchant analysis of the Friedjung trial, exposing the irresponsibility of the Foreign Ministry and the susceptibility of public opinion. In a deluded world, he wrote, Austria is the last to lose its credulity. It is the most willing victim of publicity in that it not only believes what it sees in print, but also believes the opposite, if it sees that in print too (F 293, 1). The case provided him with a model of political mystification, showing that the patriotic fervour whipped up by the press by no means lost its hold when its fraudulence was exposed. In other contexts Kraus may understate the role of governments as instigators of political mystification, treating the press in isolation, as if it were an independent force for evil. Here he does justice to all the main factors: the government as instigator, the press as its willing agency, the collusion of intellectuals, the gullibility of readers, and the impact of jingoistic slogans. He makes the probable consequences equally clear: a war in which thousands of lives will be lost.