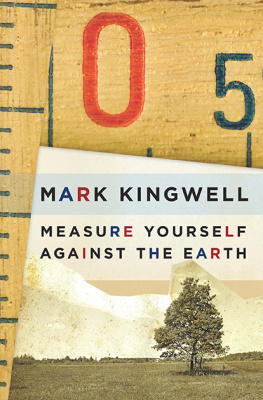

Table of Contents

Also by Mark Kingwell

Nearest Thing to Heaven: The Empire State Building

and the American Dream

Nothing for Granted: Tales of War, Philosophy, and

Why the Right Was Mostly Wrong

Classic Cocktails: A Modern Shake

Catch & Release: Trout Fishing and the Meaning of Life

Practical Judgments: Essays in Culture, Politics, and Interpretation

The World We Want: Virtue, Vice, and the Good Citizen

Marginalia: A Cultural Reader

Canada: Our Century (with Christopher Moore)

Better Living: In Pursuit of Happiness from Plato to Prozac

Dreams of Millennium: Report from a Culture on the Brink

A Civil Tongue: Justice, Dialogue, and the Politics of Pluralism

for Molly

The situation of consciousness as patterned and checkered by sleep and waking need only be transferred from the individual to the collective Architecture, fashionyes, even the weatherare, in the interior of the collective, what the sensoria of organs, the feeling of sickness or health, are inside the individual. And so long as they preserve this unconscious, amorphous dream configuration, they are as much natural processes as digestion, breathing, and the like. They stand in the cycle of the eternally selfsame, until the collective seizes upon them in politics and history emerges.

Walter Benjamin

Hard and Soft

i. Beautiful Concrete

The next time it rains, go out and touch some.

Find a wall or a bench or just a stanchion, and run your hands along the spongy, almost-smooth surface.

Feel the tough, wet muscularity of it. Skim your fingers over a few of the thousand small holesbubbles reallythat notch the outside. Pebbles and other tiny bits are lodged in the surface, looking like you might just pry them out. You will not.

Trace the little runnels that cut between the slabs, or the little circles of the snap ties. Imagine the iron rebar skeleton inside, the bones for this rugged flesh.

But before you do any of that, just look at it. Look at the chiaroscuro patterns the rain is painting on the micro-pitted planes, the way the wall seems to be weeping its way from light to dark, in running streaks, like mascara. We call it gray, as if that were one simple color, but concrete is dozens of shades at once, from various off-whites through to charcoal. It has swirls and patterns, little islands and continents stained on the extended map of its face. Concrete is beautiful, never more so than in the rain.

Yet it is a material people love to hate, for reasons lodged often in conventional disregard and a prejudice for more natural materials such as wood or finished stone. Mostly, though, it is because we have not been given the opportunity to see concrete properly. There are many spectacularly egregious examples of its abuse: squat Soviet-style blocks full of bureaucrats, and those windswept, boxy warehouses for intellectuals we call modern universities. Surely much of the hostility we feel toward concrete is owing to the brutalist annexation of its loveliness, the way it was taken over and made into those thick, tough slabs that block out the sky. Any material becomes the sum of its treatments, and concrete has been made to look leaden, solid, heavy. The standard view is summed up by the words of one architectural critic who noted that concrete has figured heavily in numerous architectural monstrosities, not least because the cheap, durable substance oozes despair and seems to suck up light.

Concrete is the basic material of the urban moment, and not just on the outside of big institutional edifices or office towers, the concrete jungle of the alienated metropolitan imagination. Witness Esther Greenwood on page one of Sylvia Plaths The Bell Jar, describing one summer in New York: Mirage-grey at the bottom of their granite canyons, the hot streets wavered in the sun, the car tops sizzled and glittered, and the dry, cindery dust blew into my eyes and down my throat. The streets themselves, particulated, rise up and cling to your skin, the windowsill, pieces of paper left undisturbed too long. A fine soot envelops every surface and recess. We begin to feel not merely dirty but as if the city is attempting, all unnaturally, to render us into its own material form.

Concrete is cheap to produce and easy to use. When in doubt, pave or pour. Perhaps too cheap and too easy. Thus the urban death maze of concrete canyons, harsh and impenetrable; the toxic city, with invisible death rays emanating from the materials palette itself, crumbling blocks of disease; the barrier or fence, blocking movement or imprisoning ethnicity. Concrete may even be implicated in a species of architectural war crime as urban planners are co-opted by the total mobilization war machine to create insurgent cities, or to destroy invaded ones more effectively: concrete as strategic intervention.

This understanding of the material is not wrong, exactly, just one-sided. In the right setting, brutalism has its own peculiar appeal, and sometimes bunker-style institutions or looming office buildings are just what we want in a hard-bitten urban landscape. Stock denunciations of concrete cloud the issue: There are lots of ugly brick and wood buildings too. More to the point, concrete is not inherently cold, inhuman or brutal. Like many good things, it can be bent to bad purposes, but we should not blame the material. Try this instead: If you treat concrete well, it will reveal new layers of possibility, new aspects of beauty.

Concrete is also expressive and rewarding, a human material for all its toughness. It is capable of making a complex statement, exciting a nuanced reaction. Concrete now decorates the interiors of downtown offices, setting off traditional high-end polished wood and frosted glass with its appealing density and strength of purpose. It provides a different, firmer kind of grace note in otherwise lush parks and public squares.

You can have it inside your home. There is concrete-patterned wallpaper, realistic right down to the gravelly details. Some adventurous designers have installed concrete counters, floors, even dining-room tables. Set off with a patch of grass, a concrete table is a study in liminality, the textures of outside brought into the heart of the cozy domestic interior.

Changes to the materials palette make other forms of liminality possible. In 2004 the young Hungarian architect ron Losonczi invented a material he called Litracon (light-transmitting concrete), made by adding glass and plastic fibers to the usual mix of sand, gravel, cement and water. A wall fashioned of Litracon is not transparent but is translucent enough to allow a play of light and shadow between inside and outside, like the thin marble panels that clad the Beinecke Library at Yale University (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, 1960-63): stone refashioned as almost glass.

![Harry Turtledove - Worlds that werent : [novellas of alternate history]](/uploads/posts/book/79050/thumbs/harry-turtledove-worlds-that-weren-t-novellas.jpg)