Contents

Guide

For all the young people who truly care about America

T.B.

To all the tirelessly dedicated librarians and educators who help shape the future

E.V.

Contents

Its not hard for powerful people to speak up for what they believe, but for the powerless it can be downright dangerous.

A T AN AWFUL MOMENT FOR THIS COUNTRY PATRICK HENRY DRAMATICALLY DEMANDED: GIVE ME LIBERTY OR GIVE ME DEATH! Those famous words directed at Great Britain have sounded down through the decades since 1775. Henrys timeless demand still echoes in our politics, because it helped define who we are as Americans.

Awful moments provided the contexts for many of these speeches. In 1796, when George Washington issued his farewell address, no one knew if the fledgling United States of America could survive without his leadership.

And in the most awful time of all for America, Abraham Lincoln stood on the battlefield-turned-cemetery at Gettysburg in 1863 and wondered if a nation conceived in liberty with a government of the people, by the people, and for the people could long endure.

Though the other speeches here dont share the fame of the Gettysburg Addressits been translated into some thirty languagesand the orators dont share the power of the president of the United States, we still hear their strong voices.

Its not hard for powerful people to speak up for what they believe, but for the powerless it can be downright dangerous. Thankfully, Red Jacket and Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass took that riskbravely calling on their fellow Americans to extend basic liberties to more and more of the nation.

Calls to actionthe only way to overcome the awful moments for the countryabound in these addresses. In 1910 Teddy Roosevelt insisted on an active citizenry in whats come to be called the man in the arena speech.

We learn from the people who stepped into that arena, often at great sacrifice. Fanny Lou Hamer described to the delegates at the 1964 Democratic Convention the torture she endured as an African American trying to exercise her right to vote in Mississippi.

Cesar Chavez, the Mexican American founder of the United Farm Workers union, explained to a gathering in 1984 how he was able to bring about better conditions for migrant workers: We organized! and then added, Once social change begins, it cannot be reversed.

But that social change does not begin on its own. Someone must call for itmust raise what is often a lonely voice to insist that all voices be heard and heeded.

Listen then to the people who created this country, kept it from disunion, and brought more of its citizens into the fullness of their rights. With the clarion call give me liberty you can hear the sounds of our timeless struggle to fulfill the promise of America, to form a more perfect union.

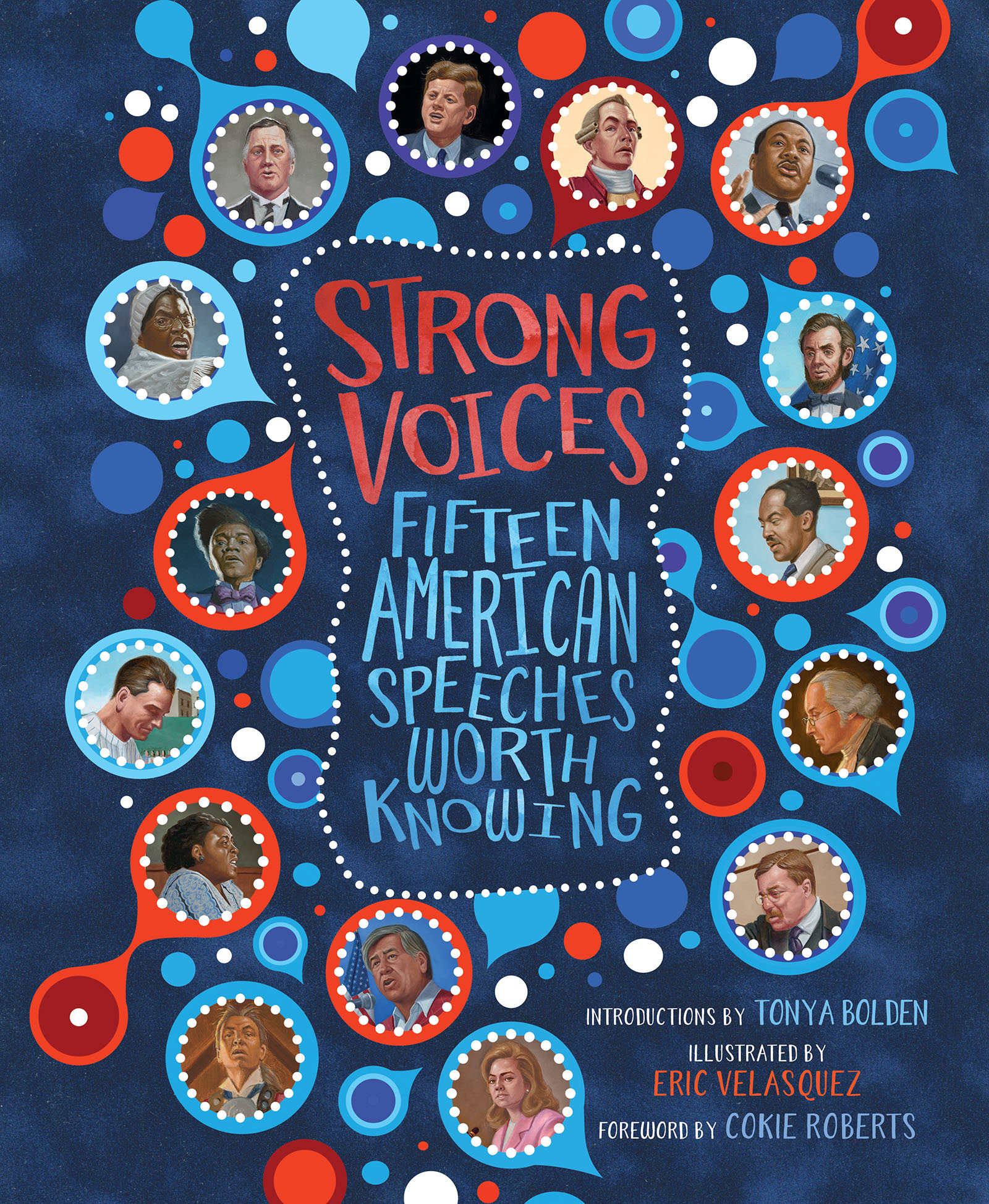

S TRONG VOICES IS A COLLECTION OF FIFTEEN AMERICAN SPEECHES. SOME YOUVE HEARD OF like Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death, or The Only Thing We Have to Fear Is Fear Itself, or I Have a Dream. They represent the greatest hitsthose that come to mind when you think of famous American speeches. Others you may have never heard of.

Some of the works in this book are complete, and some have been edited, but all have the original wordsor at least, the original words as we know them. You see, some werent written down at the time. And in some cases, they were written down by someone other than the person who gave the speech, so its complicated. Did the person who wrote it down have their own agenda? Did they alter what was actually said? Some of the speeches are very readable and easy to understandlike Lou Gehrigs Farewell to Baseball. Others are harder. For each speech, acclaimed writer and history lover Tonya Bolden provides an introductiontelling us what was going on at the time, who the person was, and what it all meant. And along the way, Bolden provides many fascinating insights. Understanding what a speech meant at the time can help unlock what it means for us today. It helps shed light on the ways this nation has changed and the ways that it remains the same.

We hope youll enjoy this look at fifteen American speeches worth knowing.

M AY 29, 1736 J UNE 6, 1799

SPEECH TO SECOND VIRGINIA CONVENTION, 1775

If we wish to be free... we must fight.

I n 1763, with the end of the Seven Years War between Great Britain and France and their allies, Great Britain controlled more territory. The new land included Canada and what would one day be the United States Northwest Territory.

But there was a downside.

Debt.

To climb out of the hole, Great Britain imposed more taxes on its thirteen North American colonies. There was the Stamp Act of March 1765, for example. It taxed all manner of printed paper, from newspapers to playing cards. Then came the Townshend Acts, taxing glass and paint, among other imported goods.

People in the thirteen colonies were outraged, especially in Boston, where King George stationed troops in 1768. It was also in Boston that, on March 5, 1770, redcoats, as British soldiers were called, fired into a crowd of rowdy colonists on King Street. The first to fall in this Boston Massacre was a seafarer of African descent, Crispus Attucks.

Three years later, in response to a tax on tea and overall British oppression, colonists staged the Boston Tea Party (December 16, 1773). Under cover of night, roughly one hundred men disguised as Mohawk Indians boarded three British ships. They then dumped more than three hundred chests of tearoughly forty-five tonsinto Boston Harbor. Britain retaliated with what Americans called the Intolerable Acts. For one thing, the port of Boston was closed until all that destroyed tea was paid fortea worth about $1 million in todays dollars. Even more infuriating, Great Britain put Massachusetts under military rule. Colonists anger over thisand over so much taxation without representation in Parliamentburned even more fiercely.

What to do?

From September 5 through October 26, 1774, white male land-owning delegates from twelve colonies (Georgia abstained) met in Philadelphia. These men decided to launch a boycott of British goods and to petition King George to repeal the Intolerable Acts. Patrick Henry of Virginia was one of the fifty-six delegates at this First Continental Congress.

Several months later, roughly one hundred white men met in Richmond, Virginias St. Johns Church for a weeklong Second Virginia Convention. (The first was held after passage of the Intolerable Acts.)

These Virginians seeking liberty from British tyranny included the wealthy slaveholders Thomas Jefferson and George Washington. Patrick Henry, a slaveholder, too, was also there. This failed grocer, failed farmer, failed shopkeeper, then bartender and fiddler, had become a successful lawyer and a member of Virginias House of Burgesses (general assembly).

On Thursday, March 23, 1775, day four of the Second Virginia Convention, Patrick Henry urged his colony to prepare to protect itself from an increasingly menacing Great Britain by raising a militia. Most delegates recoiled at the idea. That could provoke a wholesale British invasion!

When debate ceased, Patrick Henry rose from his seat with an unearthly fire burning in his eye, remembered one witness. The tendons of his neck stood out white and rigid like whipcords. Henry argued that there was absolutely, positively no hope for reconciliation with Great Britain. In closing, to the spellbound crowd, he declared

Next page