The research odyssey that has resulted in this book began at the Cornelia Street Cafe on May 23, 1985 when Edit Villareal and I interviewed Irene Fornes for an issue of Theater magazine. This first encounter catalyzed my decision to write my doctoral dissertation on Fornes at the Yale School of Drama, a project which benefitted from the wisdom and guidance of my advisor, Richard Gilman. At Yale, Stanley Kauffmann, Joel Schechter, Gitta Honegger, and especially Leon Katz sharpened my critical thinking and writing skills. Thanks is also due to Lynne Cummings for being there at the beginning.

In my work on Fornes over the years, a number of her colleagues and associates have done me the courtesy of sharing their experiences through formal interviews, casual conversations, and telephone and email communications. At one time or another, this has included Gwendolyn Alker, Devon Allen, George Bartenieff, Herbert Blau, Anne Bogart, Stephen Bottoms, Susan Letzler Cole, Migdalia Cruz, Sheila Dabney, Donald Eastman, June Ekman, Crystal Field, Susan Gregg, Rebecca High, Morgan Jenness, Larry Kornfeld, Janet Leuchter, Peter Littlefield, Bonnie Marranca, Marc Masterson, Patricia Mattick, Kelly Maurer, Michelle Memran, Anne Millitello, Aileen Passloff, Marc Robinson, Phyllis Jane Rose, Ed Setrakian, Alisa Solomon, and Caridad Svich. I thank all of them and others who I must be overlooking for their generosity and insight. In addition, I owe thanks to the many press representatives, publicity and marketing staffers at numerous theaters, and photographers who helped me gain access to production photographs and other Fornes materials.

A 20067 Research Incentive Grant from the Office of Sponsored Programs at Boston College made it possible for me to resume Fornes research for the purpose of writing this book. I am deeply grateful to the George A. and Eliza Gardner Howard Foundation for a 20089 fellowship that supported a leave of absence from teaching at a crucial stage of the writing process. Over the years, a series of undergraduate research fellows at Boston College Jenn Wade, Claire Darby, Dan Brunet, Marin Kirby, Megan Rulison, Sarah Lunnie, Dave Bruin, Sarah Lang, Han Cho, Evan Cole, Cam Cronin, and Cara Harrington provided valuable nuts-and-bolts assistance. I was aided by my students in a different way when I directed Abingdon Square at Boston College in 2004, and I thank the talented student cast Mairin Lee, Chris Tocco, Dan OBrien, Emma Stanton, Marianne Frapwell, Jonathan Popp, Patricia Noonan, Lee Trew, and cellist Adrian Curtin for their curiosity and dedication. I also want to acknowledge the support and encouragement of Morgan Jenness, Michelle Memran, and Gwendolyn Alker, whose commitment to preserving the Fornes legacy has been essential.

Patricia Noonan, Cam Cronin, Erica Stevens Abbitt, and Amanda Fazzone read all or part of the manuscript and made helpful suggestions and corrections. I am grateful for their time and attention to detail. As series editors, Maggie Gale and Mary Luckhurst have exhibited an astonishing patience with me over the years, as has Ben Piggott at Routledge all through production.

Janet, I love you and thank you for everything.

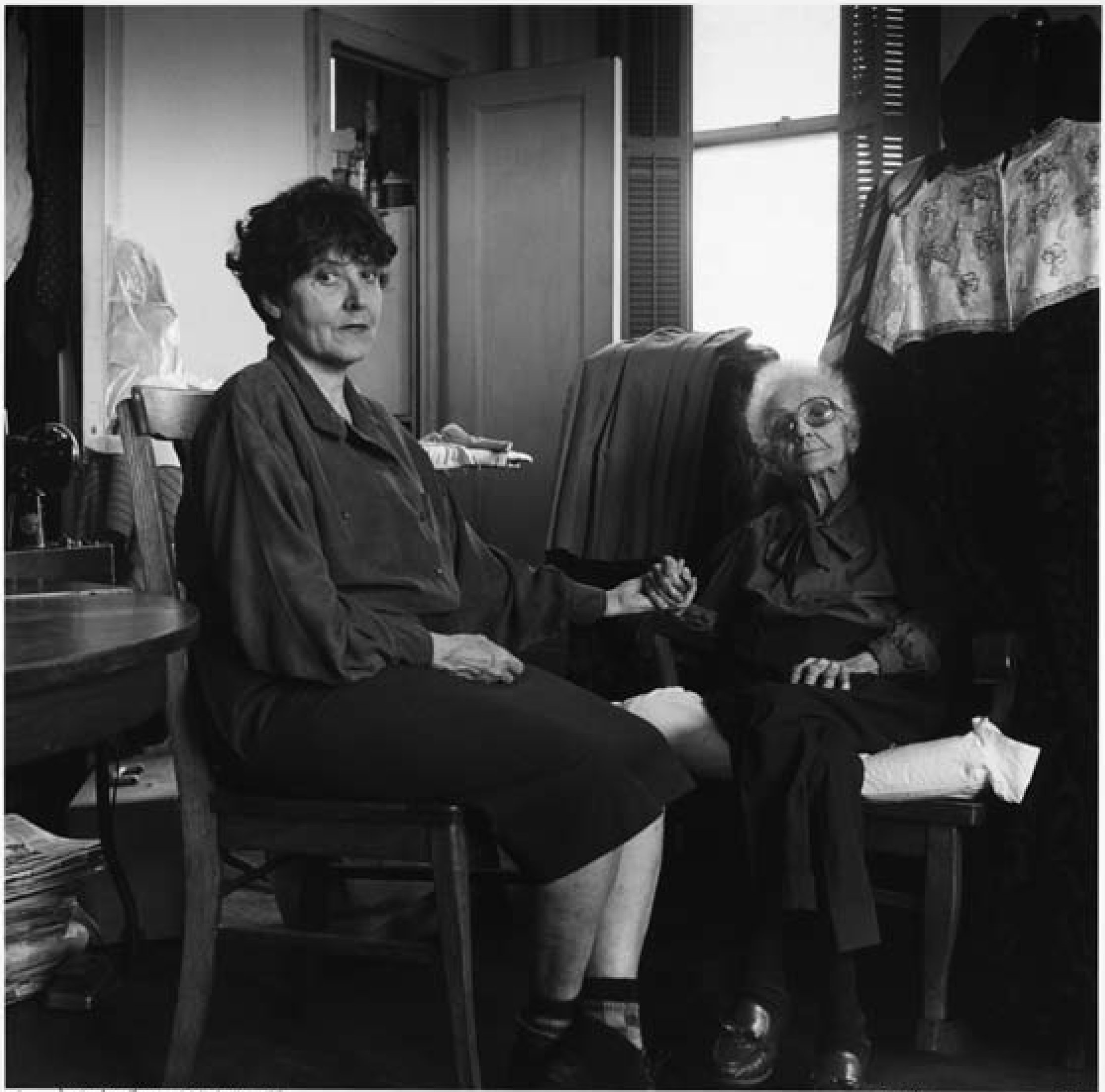

Most of all, I thank Irene. When she first agreed to cooperate with my research, I am sure she had no idea how many times I would turn up to request another interview, seek permission again to sit in on rehearsals, listen to her speak on a panel, see one of her plays, ask for a copy of a manuscript or doublecheck some information. Her willingness to share with me the intricacies and the intimacies of her creative process is a gift that cannot be measured. I am forever grateful. When I finished writing this book, I went to visit Irene in the adult care home where she lives in upstate New York. At that point, her dementia made conversation impossible, but when I asked her if she knew any good songs, her face brightened and she burst into singing Guantanamera. I joined in on the chorus, as she sang verse after verse after verse. She loves to sing. She has joy in her heart and the song of life on the tip of her tongue. I am grateful for that, too.

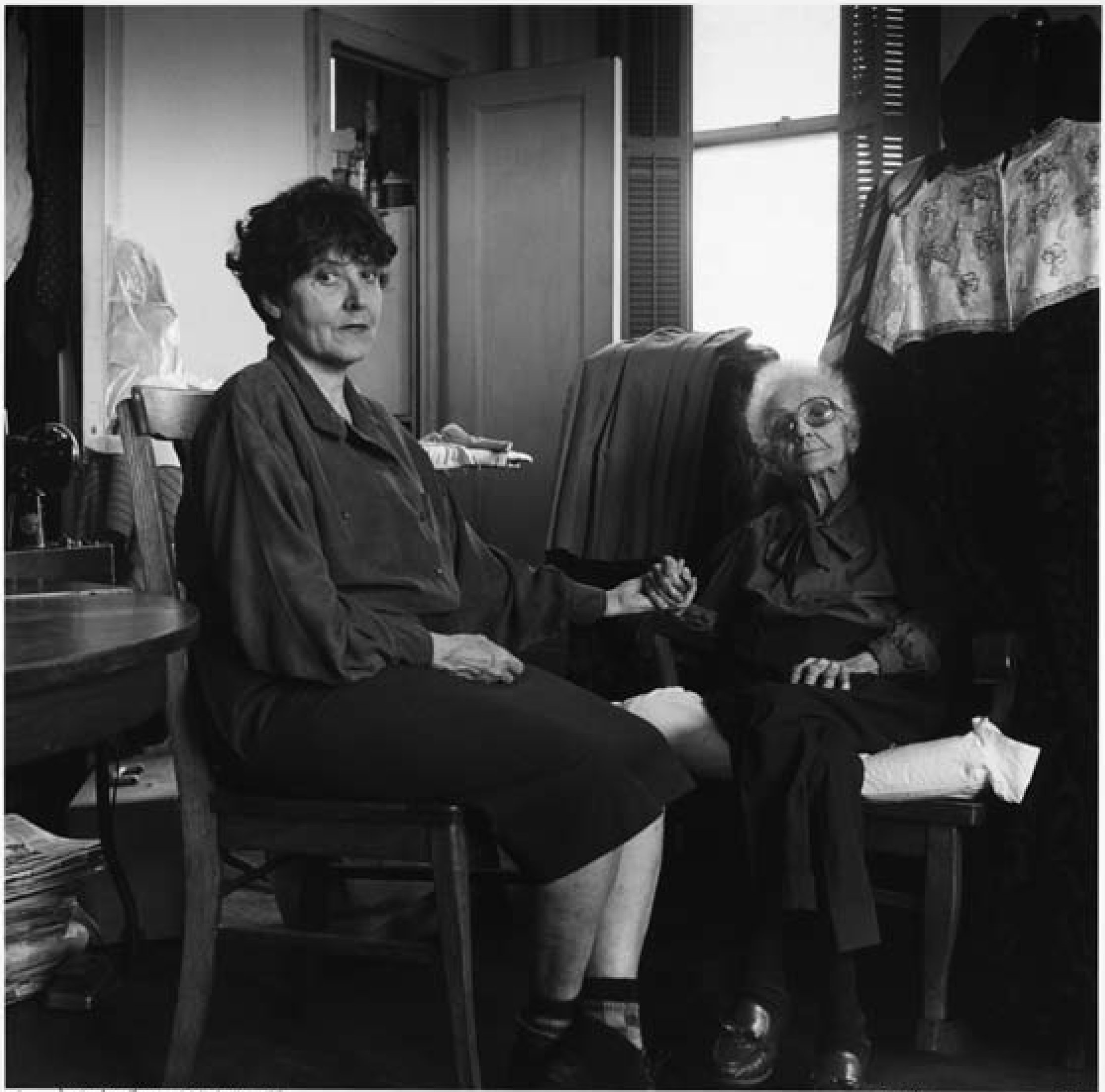

Figure 1 Maria Irene Fornes in her Sheridan Square apartment with her mother Carmen (1990).

For Fornes, the 1960s was a period of discovery, one in which she began playwriting almost by accident and then never stopped. She had no aspiration to become a playwright, but from early on she had creative inclinations that first sought expression as a painter and a textile designer. At some point early in the 1960s it is diffi-cult to pinpoint exactly when she found herself possessed by this obsessive idea, as if you have a nightmare and for a while you cant shake it (Cummings 1985: 51), and for three weeks, she wrote around the clock, calling in sick to work and stopping only to step out for groceries. The idea took shape as a one-act play. Writing it was the most incredible experience, she later said. A door was opened which was a door to paradise (Savran 1988: 55). Later, when a friend of a friend told her about a theater on the West Coast that was looking for new plays, she sent the play off on a lark. It was selected for production, paired with another one-act, and presented in the theaters second space. On November 29, 1963, at age 33, with no formal theater training or practical experience, Fornes made her professional playwriting debut.

At that time, Fornes had been living for years in Greenwich Village, the neighborhood around New Yorks Washington Square long famous as an urban bohemia and center of artistic innovation. Following World War II, the avant-garde in contemporary art shifted from Europe to the USA, leading to radical developments in all of the arts in the 1950s: abstract expressionism and action painting, the Black Mountain poets, the New York School and the Beats, the experiments of composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham, bebop bending into modern jazz, the Living Theatre, Happenings, and so on. These new forms, characterized by spontaneity, a restless, sometimes frenetic energy, and a rejection of traditional conventions, opened up realms of possibility for a new wave of artists who would define the 1960s: Warhol and other Pop Art pioneers, underground filmmakers, Fluxus, the Judson dancers, and the Off-Off Broadway theater movement. In a utopian pursuit of absolute freedom and close-knit community, these 1960s artists combined elements of elite and popular art in order to create what Sally Banes describes in Greenwich Village 1963 as a kind of avant-garde, urban, folk art:

For one thing, often the style of the works low-budget, deliberately crude, home-made, nonrealistic, small scale, often humorous or playful, improvisatory, and personal in presentation invited comparison with the rough-hewn vitality of naive painting, home movies, small-town civic pageantry, and festival occasions. For another, the content of these avant-garde works often recalled that of folk art lifes daily activities and objects, no matter how seemingly humdrum; the body in all its simultaneous grace and grotesqueness; the social life of the community. Finally, even the means of production and the functions of the avant-garde films, artworks, and performances of all kinds seemed folklike: the participants were family and friends; the materials were usually whatever was at hand; often the venues were not official stages or museums, but churches, clubs, lofts, storefronts, even homes; the audiences were local, sometimes learning about the performances through word of mouth; the times were often after-hours; the scale was intimate; and the unpolished amateur-style itself invited potential participation by anyone in the community.