This book is dedicated to

curious runners everywhere.

[Contents]

PART 1:

The Musculoskeletal System

PART 2:

The Cardiorespiratory System

PART 3:

The Metabolic System

PART 4:

The Central Nervous System

PART 5:

The Immune System

[Acknowledgments]

Ross Tucker

This book was inspired by a combination of too many people to name over too long a period to recall. However, special mentions go to Yumna, Sacha, George, Tami, Dale, Tertius, and Rob vd V. Thank you for your support, friendship, and encouragement. Rob B and Bruce Beckett provided questioning minds, ideas, and the support that turns mere science into the kind of content hopefully produced in this book. Thanks to the de Witt family for making their home available for a week and to Karlien for help with the content. For my grandmother, Joyce.

Jonathan Dugas

Thanks to my co-authors Matt and Ross for all their hard work throughout this process, especially Matt for your guidance and insight, and Ross for all your technical edits and thoughts. Special thanks to my loving wife Lara for her support during the writing of this book.

Matt Fitzgerald

I would like to thank the following special individuals for their direct and indirect contributions to this rewarding project: Jason Ash, Courtney Conroy, Eric Cressey, John Duke, Gear Fisher, Nataki Fitzgerald, Michael Fredericson, Donavon Guyot, Jane Hahn, Brad Hudson, Asker Jeukendrup, Linda Konner, T.J. Murphy, and Tim Noakes.

[Introduction]

T he human body is a marvel. Its 100 trillion frequently replaced cells (not to mention another one trillion foreign bacteria cells that live inside us) cooperate in an exquisitely choreographed dance of chemical, electrical, and magnetic interaction that is influenced in countless ways by the surrounding environment. The human body would be fascinating to study even if each of us did not inhabit one. But the fact that we are human bodies makes every new thing we learn about them an awe-inspiring step of self-discovery.

And each of these steps has the power to immediately change our lives. For example, when a person first learns that the human body requires regular exposure to natural sunlight to produce adequate amounts of vitamin D, she might make efforts to get outdoors more.

Considering that you have picked up this book, we expect that one of the ways in which you hope to change your life is by improving your running performance. Most major universities have exercise science departments where professionals like us conduct research that is relevant to the performance interests of athletes, including runners just like you. It is hardly necessary to hold a PhD in kinesiology to improve as a runner, but gaining a better understanding of the physiological underpinnings of running performance will certainly give you the wherewithal to make helpful changes to your training, with fewer missteps.

More important than remembering every detail about the physiology of running is understanding the basic principles that underlie those details. The details change as science progresses, but the principles do not. You can always fall back on the principles to guide your decision making as a runner. None of this books details is as important as the single most fundamental tenet of exercise physiology. If you come away from this book having learned only one thing, we hope that it is a full appreciation of this vital principle: the principle of stress and adaptation. Understanding it is almost like having a coach to guide you through every step of your journey as a runner.

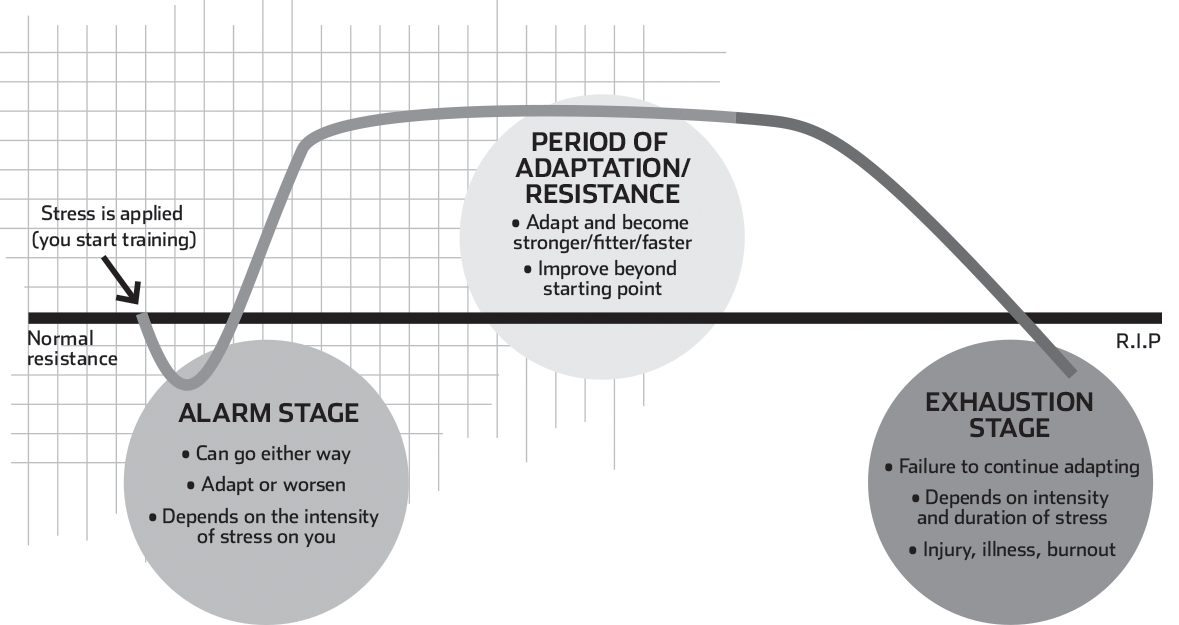

Stress and Adaptation

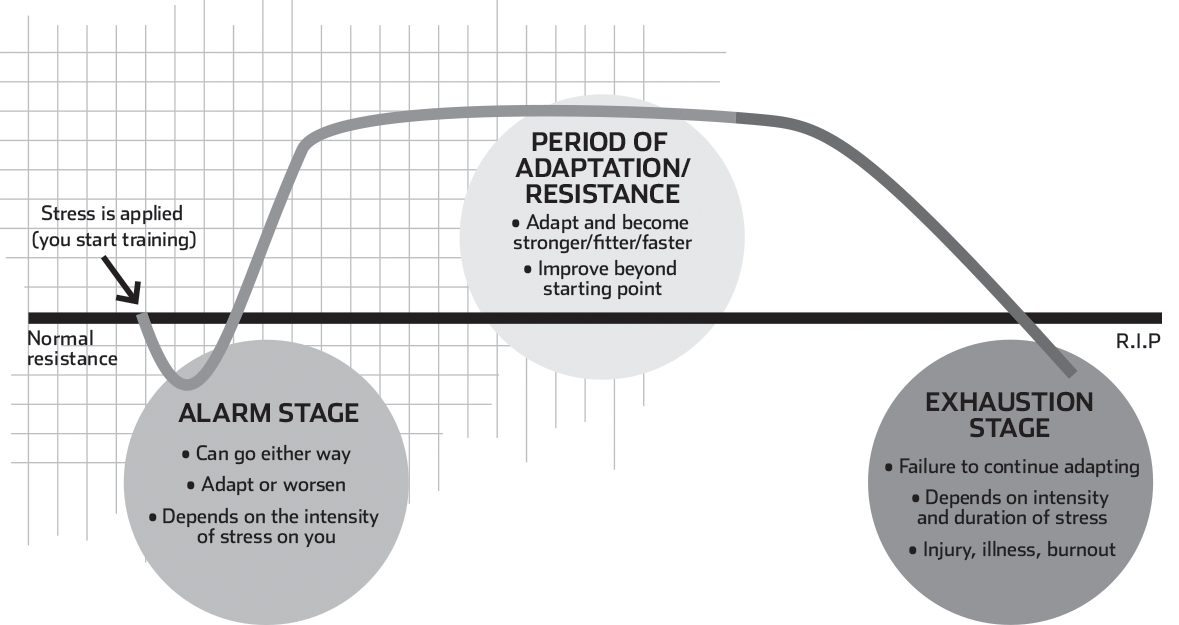

To understand the processes that occur in your body when you train, it helps to go back to 1936 and the work of a medical doctor named Hans Selye, who is regarded as the first person to demonstrate the existence of the so-called stress response. His work involved exposing mice to various stressors, including cold environments, surgical injury, doses of diverse drugs, extracts of other foreign tissues, and even excessive exercise (yes, running and other forms of exercise can be stressors!), and then measuring the physiological responses to each one. Selye found that regardless of the initial source of stress, the mice reacted with a very typical pattern of responses: an initial alarm stage, followed by a period of resistance or adaptation, when the organism gets stronger and performs better (which is, of course, where you want to be as a runner). This leads, if the stress is not removed, to exhaustion.

A greater understanding of the physiology of running can help you get into, and remain in, that stage of adaptation and avoid the unwanted stage of exhaustion, in which your body fails to adapt and instead falls prey to overtraining, injury, and burnout. See illustration opposite page.

THE EARLY PHASE: ALARM BELLS RINGING

Running stresses the bodyjust ask your nonrunning friends how they would feel if they accompanied you on tomorrows training run! In the initial, alarm stage, when that stress is first applied, your body can change in one of three ways, depending on the magnitude of the stress:

If the training stimulus is of optimal duration and intensity (youll see exactly what we mean by optimal later on), your body begins adapting.

If the training stress is too great, you will break down almost immediately, develop injuries, feel excessive fatigue, and fail to recover from one day to the next. All in all, training will be a very unpleasant experience, and you will probably retire from running or take up another sport.

If the training stimulus is relatively weak and does not really test your physiological systems, your body will not see any need to make adaptations, and you will remain at the same level. This is a concern for runners who have reached a performance plateau. You might have been training for months or years and find that youre no longer improving. One possible reason (there are a few) is insufficient training stress.

So its absolutely vital that you manage training stress wisely by controlling the various elements that determine its magnitude. These elements include:

Volume, which is made up of two aspects:

Volume, which is made up of two aspects:

Duration: How far or for how long you run

Duration: How far or for how long you run

Frequency: How often you run

Frequency: How often you run

Intensity: How hard you run. This is often the straw that breaks the camels back, since its subjective and therefore difficult to measure and control.

Intensity: How hard you run. This is often the straw that breaks the camels back, since its subjective and therefore difficult to measure and control.

Volume, which is made up of two aspects:

Volume, which is made up of two aspects: Duration: How far or for how long you run

Duration: How far or for how long you run