T HIS I S A B ORZOI B OOK

P UBLISHED BY A LFRED A . K NOPF

Copyright 1994, 2001 by Mark Strand

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Hopper was originally published in different form in hardcover and paperback by The Ecco Press, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, in 1994 and 1995 respectively. This edition was published in paperback and in slightly different form by Alfred A. Knopf in 2001.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Strand, Mark, [date]

Hopper / by Mark Strand.1st Knopf hardcover ed.

p. cm

A Borzoi Book.

Redesigned and with color platesT.p. verso.

Originally published: Hopewell, N.J.: Ecco Press, 1994.

eISBN: 978-0-307-95710-8

1. Hopper, Edward, 18821967Criticism and interpretation.

I. Hopper, Edward, 18821967.

II. Title.

ND 237. H 75 S 76 2011

759.13 DC 23 2011024576

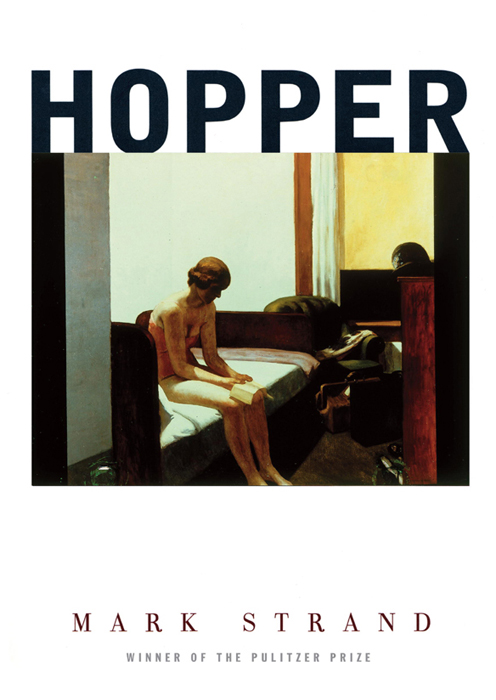

Jacket image: Hotel Room, 1931, by Edward Hopper.

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza / Art Resource, N.Y.

Jacket design by Abby Weintraub

v3.1

to Judith and Leon

Contents

Preface

My purpose in writing about the paintings of Edward Hopper was not only to clarify my own thinking about them but to correct what I perceived to be misconceptions advanced by other critics of his paintings. Much that had been written seemed to skirt the central issue of why vastly different people should be so similarly moved when confronted with his work. My approach to this and related issues has been largely aesthetic. I am less interested in the evidence of social forces in Hoppers work than I am in the presence of pictorial strategies. To be sure, his paintings represent a world that looks somewhat different from ours. However, the satisfactions and misgivings having to do with changes in American life during the first half of the twentieth century cannot, by themselves, account for the strong response in most viewers. Hoppers paintings are not social documents, nor are they allegories of unhappiness or of other conditions that can be applied with equal imprecision to the psychological makeup of Americans. It is my contention that Hoppers paintings transcend the appearance of actuality and locate the viewer in a virtual space where the influence and availability of feeling predominate. My reading of that space is the subject of this book.

M.S.

I

I often feel that the scenes in Edward Hopper paintings are scenes from my own past. It may be because I was a child in the 1940s and the world I saw was pretty much the one I see when I look at Hoppers today. It may be because the adult world that surrounded me seemed as remote as the one that flourishes in his work. But whatever the reasons, the fact remains that looking at Hopper is inextricably bound with what I saw in those days. The clothes, the houses, the streets and storefronts are the same. When I was a child what I saw of the world beyond my immediate neighborhood I saw from the backseat of my parents car. It was a world glimpsed in passing. It was still. It had its own life and did not know or care that I happened by at a particular time. Like the world of Hoppers paintings, it did not return my gaze.

The observations that follow are not a nostalgic look at Hoppers work. They do, however, recognize the importance for him of roads and tracks, of passageways and temporary stopping places, or to put it generally, of travel. They recognize as well the repeated use of certain geometrical figures that bear directly on what the viewers response is likely to be. And they recognize that the invitation to construct a narrative for each painting is also part of the experience of looking at Hopper. And this, inasmuch as it demands an involvement in particular paintings, indicates a resistance to having the viewer move on. These two imperativesthe one that urges us to continue and the other that compels us to staycreate a tension that is constant in Hoppers work.

II

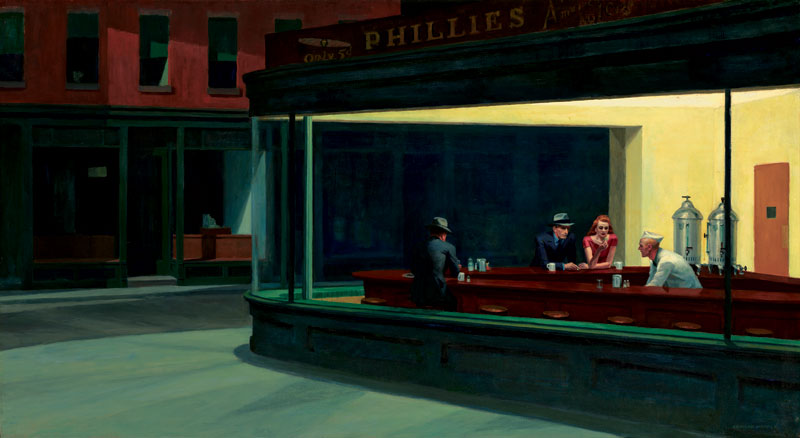

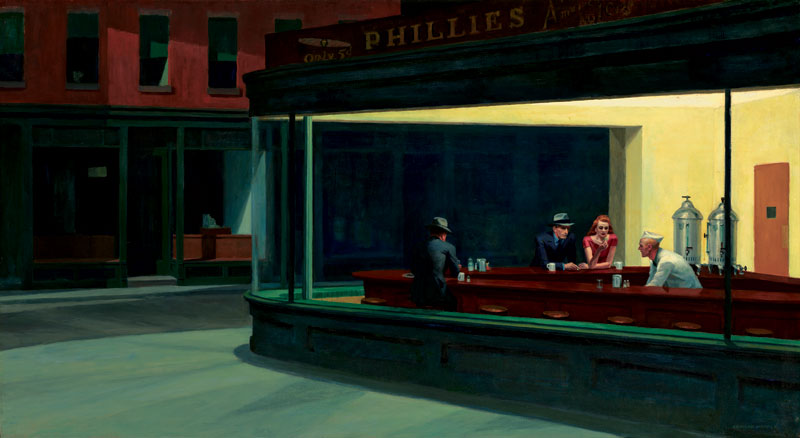

I n Nighthawks, three people are sitting in what must be an all-night diner. The diner is situated on a corner and is harshly lit. Though engaged in a task, an employee, dressed in white, looks up toward one of the customers. The customer, who is sitting next to a distracted woman, looks at the employee. Another customer, whose back is to us, looks in the general direction of the man and the woman. It is a scene one might have encountered forty or fifty years ago, walking late at night through New York Citys Greenwich Village or, perhaps, through the heart of any city in the northeastern United States. There is nothing menacing about it, nothing that suggests danger is waiting around the corner. The diners coolly lit interior sheds overlapping densities of light on the adjacent sidewalk, giving it an aesthetic character. It is as if the light were a cleansing agent, for nowhere are there signs of urban filth. The city, as in most Hoppers, asserts itself formally rather than realistically. The dominant feature of the scene is the long window through which we see the diner. It covers two-thirds of the canvas, forming the geometrical shape of an isosceles trapezoid, which establishes the directional pull of the painting, toward a vanishing point that cannot be witnessed, but must be imagined. Our eye travels along the face of the glass, moving from right to left, urged on by the converging sides of the trapezoid, the green tile, the counter, the row of round stools that mimic our footsteps, and the yellow-white neon glare along the top. We are not drawn into the diner but are led alongside it. Like so many scenes we register in passing, its sudden, immediate clarity absorbs us, momentarily isolating us from everything else, and then releases us to continue on our way. In Nighthawks, however, we are not easily released. The long sides of the trapezoid slant toward each other but never join, leaving the viewer midway in their trajectory. The vanishing point, like the end of the viewers journey or walk, is in an unreal and unrealizable place, somewhere off the canvas, out of the picture. The diner is an island of light distracting whoever might be walking byin this case, ourselvesfrom journeys end. This distraction might be construed as salvation. For a vanishing point is not just where converging lines meet, it is also where we cease to be, the end of each of our individual journeys. Looking at Nighthawks, we are suspended between contradictory imperativesone, governed by the trapezoid, that urges us forward, and the other, governed by the image of a light place in a dark city, that urges us to stay.

Here, as in other Hopper paintings where streets and roads play an important part, no cars are shown. No one is there to share what we see, and no one has come before us. What we experience will be entirely ours. The exclusions of travel, along with our own sense of loss and our passing absence, will flourish.